They may be sadistic figures who hate children, but a study suggests that the savage portrayal of headteachers in children's literature possesses a grain of truth and may even be helpful when it comes to training teachers who aspire to lead schools.

Characters like Miss Agatha Trunchbull, from Roald Dahl's Matilda, or the Demon Headmaster, from the sequence by Gillian Cross, can teach children to think about power and how it can be used for malign purposes, Professor Pat Thomson, director of the centre for research in schools and communities at Nottingham University school of education, has found.

The study of 19 fictional headteachers found that nine are portrayed as evil or authoritarian, a further six are remote figures of power, and just one - JK Rowling's Professor Albus Dumbledore - is a positive role model.

The study traces the origins of school stories to 19th century British fiction which - in stories aimed at boys - focused on the muscular discipline and militarism required for empire building.

The books in the study were published between 1975 and 2009, and included Robert Cormier's The Chocolate War and Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events as well as Matilda and Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone.

Many of the books show power can be used corruptly, according to Prof Thomson.

Sometimes this can have a contemporary, political twist: in The Inflatable School by Peter Wynne-Willson, the "evil, messianic" Mr Stemple plans to turn his school into an academy sponsored by a business with whom his family has a profitable relationship.

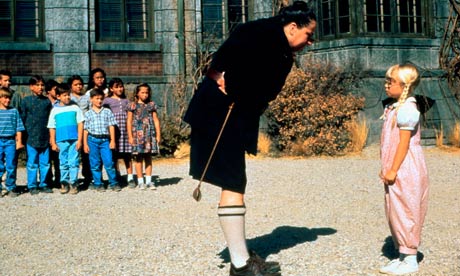

Miss Trunchbull is one of only two female heads in the books studied and is described, as "formidable and repulsive". Thomson says Matilda's triumph over Miss Trunchbull - who is replaced by the forgiving Miss Jennifer Honey - as "designed to show the benefits of the gentle use of pastoral power".

In a study to be presented to the British Educational Research Association's annual conference at Warwick University today, Thomson says the books' willingness to encourage children to think about power may help to make the stories more truthful than many adult discussions about school leadership. The books encouraged children to take responsibility and overturn unreasonable social conventions. The stories also acted as cautionary tales, warning that children who made the wrong choices must learn to be responsible.

Children were encouraged to acquire self-discipline "not because of the need for adult citizens to serve God and empire as in the traditional school story, but rather because the ... modern citizen needs to serve and save themselves in a world where adults are often fallible, self-serving and myopic, and sometimes venal, corrupt and brutal."

Power is often regarded by real headteachers as a dirty word not to be discussed,says Thomson, while serious texts on school management often avoid identifying the head's central task as the exercise of power. Children's books could be used as part of school leadership courses to address this gap.

"Children's stories come clean about headteachers' work in ways that mainstream educational leadership texts often do not," Thomson concludes. "The implied reader of children's books is a child who recognises that power can be used wisely and to ethical ends - or not; who understands that pupils can use their individual and collective power to challenge authority."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter