OF THE

TIMES

We'll know our disinformation program is complete when everything the American public believes is false.

The mentioned US plan of a greater Middle East war worked out as well as the WEF's "Great Reset" plan.

These two figures in the top image are perfectly representing the current depravation of the West. You'll also receive The Crypto Capitalist...

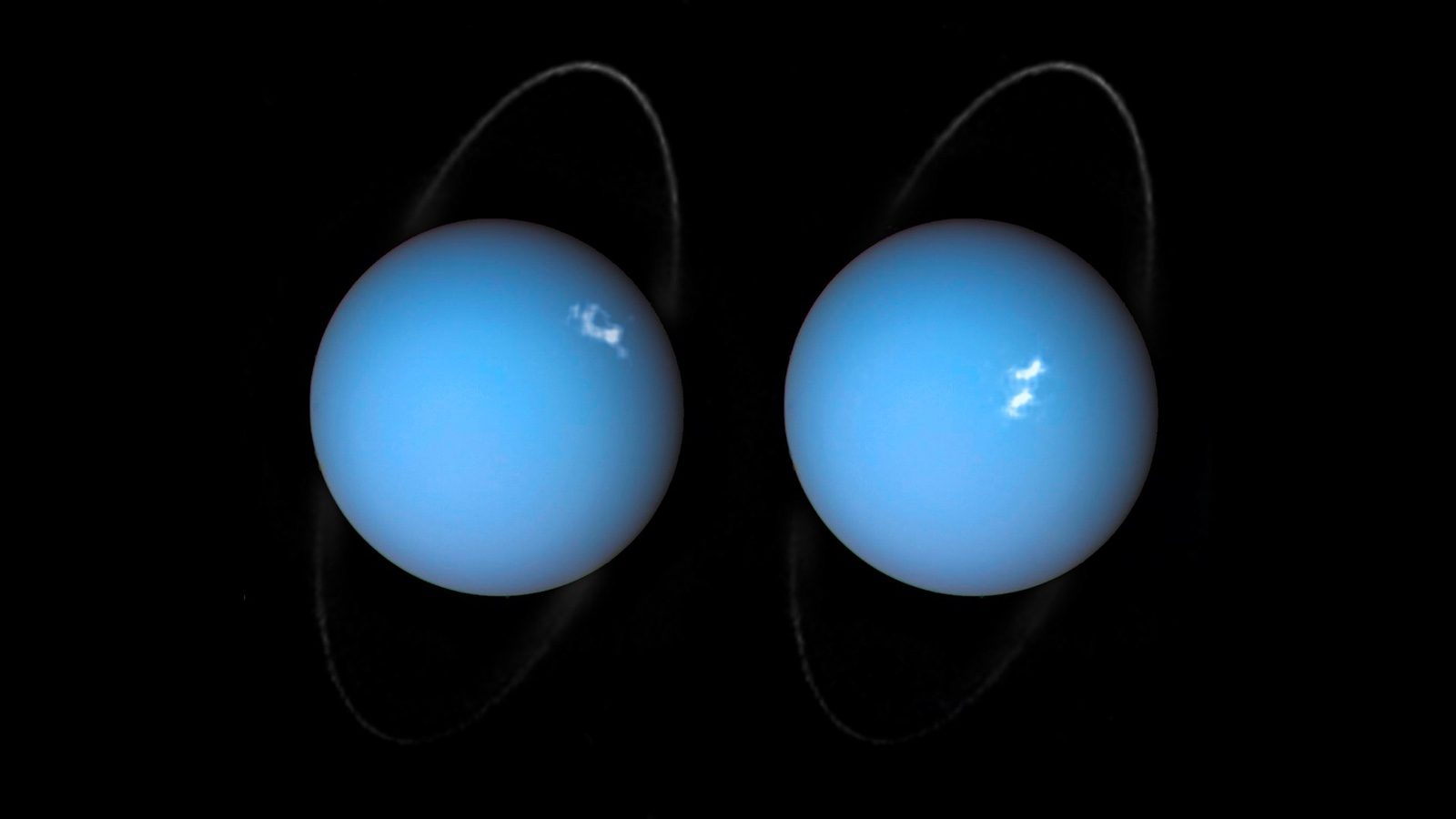

Mars-Saturn conjunction: Artworks uncovered in Pompeii excavation [Link] #astrology

At about 1:33:00 Joe is talking about Kate and cancer. On GlobalResearch Dr. Makis regularly publishes the results of vaxes. In yesterday's...

Another airhead on the airwaves...

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

Reader Comments