On this episode of the Truth Perspective, we discussed this evidence, Secretary General Hammarskjold, the circumstances of his death, and why it matters today. Joining us was Dr. Henning Melber, Director Emeritus and Senior Advisor of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation in Uppsala; Senior Advisor to the Nordic Africa Institute; Extraordinary Professor at the Department of Political Sciences/University of Pretoria and the Centre for Africa Studies at the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein; and Senior Research Fellow with the Institute for Commonwealth Studies at the University of London. He has published several books, including Peace Diplomacy, Global Justice and International Agency: Rethinking Human Security and Ethics in the Spirit of Dag Hammarskjöld.

Running Time: 02:04:51

Download: OGG, MP3

Links

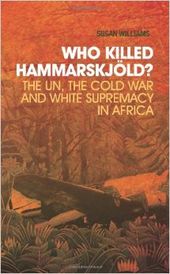

- Susan Williams's Who Killed Hammarskjold? (2011)

- The Hammarskjold Commission Report (2013)

- UN Report of the Independent Panel of Experts (2015)

Harrison:On the night of September 17, 1961 the Second Secretary General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld was flying to a meeting in Northern Rhodesia to negotiate a possible resolution to the conflict in the newly independent Republic of the Congo. His flight never reached his final destination. The next day the site of its crash was discovered just miles from the airport. Fifteen passengers including Hammarskjöld were dead and the only survivor died soon after. Written off as the result of pilot error by the official Rhodesian inquiry, the UN's own investigation did not come to any definite conclusions. But now, over 50 years later, new evidence has come to light that raises the distinct possibility that Hammarskjöld's plane was attacked. On this episode of The Truth Perspective, we will be discussing this evidence, Secretary General Hammarskjöld, the circumstances of his death and why it matters today.

In the studio we have Carolyn McCallum.

Carolyn:Hello.

Harrison:Elan Martin.

Elan:Hi everyone.

Harrison:And myself, Harrison, Koehli. Joining us today is Dr. Henning Melber. Henning is Director Emeritus and Senior Advisor of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation in Uppsala, Senior Advisor of the Nordic Africa Institute, Extraordinary Professor at the Department of Political Sciences, University of Pretoria and the Centre for Africa Studies at the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein and Senior Research Fellow with the Institute for Commonwealth Studies at the University of London. He has published several books including Peace Diplomacy, Global Justice and International Agency: Rethinking Human Security and Ethics in the Spirit of Dag Hammarskjöld. Henning, thank you so much for joining us here today.

Henning:I thank you very much for giving me the forum and the opportunity to exchange views with you. I think you have a fantastic channel and I feel honoured and truly recognize that you think that I deserve to be joining you on that conversation.

Harrison:Well thank you! That means a lot to us to hear that too. To start out with, I personally have mentioned Hammarskjöld on this show several times in the past but I'm sure that many listeners probably still don't know that much about him. So just as an introduction, can you tell us a bit about who Dag Hammarskjöld was?

Henning:Dag Hammarskjöld was born in 1905 as the son of a very traditional Swedish family and he embarked on a career as a Swedish civil servant. He was then studying among others, law, languages and economics and he was doing his PhD as an economist with the famous Gunnar Myrdal. Then he embarked on a career as head of the Swedish Central Bank and at the same time as the state secretary of the finance ministry, which funnily enough in those days, in the late '30s/early 1940s, was not considered a conflict of interest.

Hammarskjöld never was a member of a political party but he was part of the architecture of the Swedish welfare state. He then became involved in the Marshall Plan after World War II and then moved on as a diplomat to the United Nations and became the permanent representative of Sweden. But he was not very much known, he didn't really have a high profile. He was never loud. He was one of those typical modest, laid-back Swedish diplomats and civil servants and that was the reason, as we can say today, why his name came up as the potential candidate for being the Second Secretary General of the United Nations, replacing the Norwegian Trygve Lie, a trade unionist who was fond of alcohol and considered to be an unguided missile. The big powers all shared a dislike of him because you could never plan what he would do next.

They did assume, after not agreeing on any other candidate, that maybe this very unknown Swedish civil servant, Dag Hammarskjöld, who was proposed by the French diplomat in the Security Council, might be exactly the Secretary General they were looking for; someone who is secretary and is an instrument and obeys what the big powers want him to do and boy, how wrong they were!!

I think if they would have known then what they knew in the late '50s he would have never become a secretary general and already to pre-empt a question for today, would anyone of the calibre of Dag Hammarskjölds be standing a chance to become the next secretary general or anyone after him, the answer would be a very clear and obvious no. So Hammarskjöld actually turned the virtues which were considered to make him suitable for the big power interests, into a strength of becoming what in today's jargon one could say was a non-hegemonic secretary general who also turned out to be more general than secretary and who defined his loyalty right from the beginning as a loyalty towards the charter of the United Nations and the values and principles in all the global governance normative frameworks. When the powers of this world were not in agreement with the charter then it was something Hammarskjöld was not willing to play along with.

So very soon actually into his first term of office or later into his second term of office he was actually rather proud of a cartoon which showed the French head of state Charles de Gaulle meeting the Russian head of state Nikita Khrushchev and Khrushchev was wearing a badge saying "I don't like Dag" and Charles de Gaulle was wearing a badge saying "I don't like Dag either". And he sent it to a friend in Sweden and said "That's a reason to be proud".

So Hammarskjöld, to bring it back to those listeners who wonder who is Hammarskjöld, basically they share the same reaction by the way, as most in the security council in 1953 when it was discussed. When the French diplomat said "Oh there is this Swedish civil servant Hammarskjöld most of those in the security council said 'Who?'" which was actually considered a recommendation because he was unknown. And they thought, "Okay, he is the type of person we can mold. He will be the type of person who will follow the big power politics."

Now he was not very well known, but then the first thing he did when he went to the United Nations - and by the way, he was asked on the first of April, 1953 by the media, if he has heard that he is nominated for the position of secretary general and he truly thought it was an April Fool's joke, only realizing the next day that it was serious and it took him one or two days of soul-searching before he accepted.

So when he arrived in New York he was welcomed by his Norwegian predecessor Trygve Lie who said "Welcome to the most impossible job in the world." And what he did already then which speaks to his character, maybe sometimes even to his naivety, the first thing he did was to walk, in the United Nations building, from floor to floor and shake hands with each and every staff member of the United Nations. He started off initially to have his lunch in the cafeteria only he was advised he can't do that because he doesn't have the time for doing that.

But the next very political thing he did, he was throwing out the FBI of that time, dismissing all the US American international civil servants in the United Nations because that was the time of the McCarthy era and the witch hunts and Hammarskjöld said "International civil servants are on duty for other things and if they are meet the tasks they are supposed to do I don't care what political background they have." And he literally kicked out the FBI from the United Nations building. That was in '53/'54. So quite amazing for someone who was not known at that time and already pointing into the direction that for him, the international civil service is almost something holy that you do not touch, by particularly narrow-minded nationalist interests.

Harrison:Well I think it's funny you mention that they told him that he didn't have the time to do that. From what I've read about Hammarskjöld, he had a lot more time than most people because he was so dedicated to his job that he only got four or five hours of sleep and I get the impression that he was the first guy in the office in the morning and the last to leave at night. Is that right?

Henning:Yeah, it's true. He was a complete workaholic. That's also one of the important reasons why he stayed single all his live, because he felt he did not have the time to reconcile his duties with private life and family. He had a limited private life in the sense that he cultivated quite a number of remarkable interests in the arts and in philosophy and in mountain hiking. But he was really working 24/7 one could say. It's amazing if you visit the archives and you look at his private correspondence, the amount of letters he was writing by hand in those days or with a typewriter. Those were communication technologies we would consider as completely anachronistic. You go through what he was like even while he was on duty as the secretary general and you go through all the speeches, I think he was the secretary general who drafted most of his speeches alone and presented those speeches as a kind of pragmatic policy documents. He was presenting at a lot of universities often in the USA and they were pragmatic but at the same conceptual and bordering on the visionary.

If you look through what he did in those years, it's mindboggling because you ask yourself did he sleep at all. Some of the staff close to him also said it could happen that the phone would ring at 3:00 in the morning. There's nice anecdotal evidence from one of the translators. He was called out of bed at 3:00 in the morning and was asked to see the secretary general because of some unclear translation he did from French into English or the other way around and all he could say was "Could I have an hour to come because first I have to get up and dressed?" And then Hammarskjöld said "Well it's fine if you're there by 5:00."

But that was the kind of work he did and at times it was cruel to some of those around him because sometimes he tended to forget that others were not able to keep up that pace. That by the way includes the bodyguards. They were afraid when he went for a weekend outside of New York because he liked to walk, but he was walking so briskly that the bodyguards hardly could cope with his pace so they actually didn't like the outings for the weekends, which were supposed to be relaxing because they said physically that drove them to the limits. For him mountain hiking was actually a metaphor for that. He used it very often as a picture in his personal notebook which was translated under the title Markings where he sort of said "Compare the duties of his job with something like hiking in the mountains, mountaineering where you have to give the last of your energy and resources to reach the top. But once you are there you are rewarded for all the labour you have invested before."

Elan:He sounds like he was quite a remarkable man.

Henning:Well he sounds scary sometimes. {laughter} I've been working long enough on Hammarskjöld, I really admire him but it's also scary. And sometimes actually, I must say quite honestly - especially reading his notebook - I sometimes also felt sorry for him because I'm sure he had some pleasure in life but he was haunted by fulfilling his duties. He had an ethic which was much inspired by one could say the protestant ethic, even if he was much more ecumenical, but for him life was a duty and he acted accordingly. Sometimes when I've read some of his entries in the private notebook I thought that's something you can't only admire. You actually should sometimes even feel sorry for the guy.

Carolyn:It seems that as much as he felt the weight of his position, it also must have seemed to him to present a unique opportunity to bring this particular ecumenical brotherhood vision to light. He was absolutely the man for the time.

Henning:Yeah, you're right. And sometimes he even used comparisons like saying "The United Nations are a secular church", something like that. Or he repeated in his speeches used the notion of solidarity. For him the United Nations was an organization of solidarity. It's very interesting and maybe one of the less highlighted aspects; he was the secretary general at the time, not only at the height of the Cold War, which one needs to keep in mind, which already made the position a mission impossible, but it was also the time of the awakening of the African continent, the decolonization of Africa.

The winds of change, was a term that was used by the British prime minister, Harold Macmillan in 1960. Dag Hammarskjöld was the secretary general when the winds of change were blowing and he was always aware of these winds of change and he was always aware of the multiple identities but never abandoned the common ground of humanity. He was reconciling so-called "otherness" with the commonness of human beings and I think that was one of his major achievements and he also lived up to that.

Some of his visits to countries of the so-called global south like India or Tunisia of those days, they were so remarkable in the way he was able to relate to the people. Maybe one simple example for that was John Steinbeck who was a friend of his, asked him once what he, Dag Hammarskjöld would do to find out more about other people and his answer was "Sit on the ground and listen". And I think for a secretary general even of those days that was just amazing to have such an approach, the recognition of the others as equal.

One of my favourite photos is a visit of Hammarskjöld to kindergarten in Israel by Palestine and Lebanese kids and he is pictured going down on his knees and talking to the children at their height and I think that's an extremely powerful, visceral message because normally when you see those statesmen or stateswomen and others when they try to be pictured they lift up the children on their arms. But it's a completely different story that you go down to their height and look into their eyes. And I think that is just amazing. It's a story that speaks so much to his approach, of his humanity, of his willingness but also ability to recognize the other in his or her own right. I think that was something like a thread throughout all the things he did.

Harrison:Yeah. You mentioned decolonization and you used a word earlier for Hammarskjöld's view of international civil service being anti-hegemonic. I've read several times that people thought of Hammarskjöld and I think Hammarskjöld thought of himself, as a representative of the weak and the small nations and the nations and people that needed a voice that didn't have it in this hegemonic system with these two super powers at the time. So he really was a peoples' secretary general and that got him into a lot of hot water, like you said about that cartoon that he sent out with de Gaulle and Khrushchev saying "I don't like Dag" or something like that. So he did have a lot of enemies in what I might call the places of power in the world, the people that hold the big money and the big power.

So putting that together with the picture that you just painted of Hammarskjöld, he was an expert diplomat and negotiator. I think that's one of the things that made him famous in his role was his skill at negotiating. I'm not an expert on his history and his accomplishments but some of the things that come to mind were his involvement in negotiating the US troops that had been arrested and held in China.

Henning:Yes.

Harrison:He negotiated during the Suez crisis in was it 1958?

Henning:1956.

Harrison:1956. And then leading up to that with the decolonization of Africa, on the night that he died, like I mentioned, he was actually on a flight to visit and speak with the self-declared leader of Katanga, which had seceded from the Congo. So there was a conflict going on in the Congo at the time because Lumumba had been the first president or prime minister of the Congo and he had been assassinated. Katanga had separated and had the vast majority of the resources in the Congo and was supported by the international, multi-national corporations there, the mining interests and Belgium, France and the UK all had interests in that region. They had a lot of money invested there. That's where they got a lot of not only the resources but money, so they were supporting Tshombe who the Katangese leader at the time and they were actually fighting with the UN. There was a UN operating going on there. There were UN peacekeepers and there was actually fighting going on.

So Hammarskjöld had been sent there. Can you tell us a bit about that; about what was going on in the Congo and what Hammarskjöld was doing there?

Henning:Yes of course, but since we seem to have a little bit more time, can I start with the other two examples you also mentioned before?

Harrison:Absolutely.

Henning:Because I think they very much speak to his approach which then coined the expression silent diplomacy as in Hammarskjöld is the one who consolidated the beginning of so-called silent diplomacy. And the first thing he did which was really his masterpiece in getting accepted by the big powers was considered to be a mission impossible. It was indeed as you said, to try to release prisoners of war that were taken by Red China, the Peoples' Republic of China in the Korean War. These were pilots of a US American plane. But the USA then said "They were captured on a United Nations mission and it would be the task of the Secretary General to negotiate their release.

Now that was at the time, '54, '55, where Red China was not a member of the United Nations, where hardly any countries had any diplomatic relations to China. So everyone said "This is impossible! How should he do that?" Well, he had a close relative who was with the Swedish embassy in China. Sweden as a neutral country was one of the very few western countries with diplomatic relations to China. So Hammarskjöld went on a "private", completely private visit to the Peoples' Republic of China and of course everyone including the Chinese knew that this was not a private visit. He made it very clear that he was not coming as the UN Secretary General and the Chinese said yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah and being aware the UN Secretary General was coming.

And he met with Zhou Enlai who was then the foreign secretary of state in China and reportedly according to what we know - there are now official protocols - but reportedly they were talking about everything in the world except politics. They were talking about culture. They were talking about fine arts. They were talking about religion, whatever. And both of course knew that they were talking about something which they never mentioned. And once back in the office when his birthday came in 1955, he got a birthday card from Zhou Enlai where he sent him birthday wishes and mentioned that the same day the US American prisoners of war would be released.

Carolyn:There you go.

Henning:So that's how you do it. {laughter}

Carolyn:So he met Zhou Enlai at his level and what he wanted to talk about and basically acknowledged this man's humanity, his country's existence.

Henning:Absolutely.

Carolyn:And that's the way to do it. Absolutely.

Henning:Absolutely. You recognize the other. You are willing to also recognize that the other has legitimate interests. You show respect for those interests and through that you create a basis which stands a good chance of having some mutual understanding which might lead to a compromise which is in the interests of both. And that's exactly what he achieved.

And along similar lines he was really smart at the Suez crisis because that was when France and Great Britain agreed with Israel that the announced closure of the Suez Canal or bringing it into Egyptian possession would be against their interests and they really developed a war plan to occupy parts of Egypt and the Sinai. And at that time Hammarskjöld had it at his fingertips that neither the Soviet Union nor the USA were interested in that and did not consider it as a solution. So what he managed was in the Security Council, that the USA and the Soviet Union in 1956 agreed for the first time to give a mandate to a United Nations Mission. That was the establishment of the Blue Helmets and the Canadian foreign minister Lester Pearson was the co-architect of that, that the UN could send a military presence through the Suez to prevent a war there.

The UK and France grudgingly had to play along because they couldn't object to something the USA agreed upon together with the Soviet Union. That was an absolute masterpiece. But at the same time it also showed the limitations of the secretary general's office because much to his frustration he was unable to get a mandate to intervene in Hungary. What was happening at the same time when the Hungary government with friendly relations to the Soviet Unionm asked them to bring in their troops and occupy Hungary to rescue them from a popular revolt. And Hammarskjöld went on record in the security council where he said with reference to the Suez that the same kind of intervention would have been required in another case where he unfortunately was not able to get the mandate.

So while he was successful in certain constellations, the Cold War prevented him from being successful in other confrontations. 28:04 He was not able to intervene in South America, treated by the USA like their backyard where they replaced regimes to their liking. Hammarskjöld did not approve that but he couldn't do anything because he did not get a mandate from the United Nations. I mentioned Hungary. He couldn't do anything about the atrocious warfare in Algeria between French troops and the anti-colonial movement. He couldn't do anything in '61 in Bizerte, again in Tunisia, with the conflict between Tunisia and the French because he didn't have a mandate. But he was successful in some situations. He was unable to bring about anything similar in other situations because he didn't manage to get the mandate.

To get support however, he also realized very quickly he needed to rely on a support basis from what we would call today the global south, the non-allied movement which was in formation since the Bandung, (Indonesia) conference of 1954 I believe (actually 1955). For example for Congo, he asked the permanent delegate of Tunisia to submit a draft resolution to the security council, being aware that the Soviet Union would not be able to veto a draft resolution that was submitted by the Tunisian permanent representative. So they instead abstained. And he played along that way in the Suez crisis and then later in the Congo when for example, the question was who would be deployed as the UN Blue Helmets and he always resorted to those countries. It was Egypt - well not in the Suez crisis, but only then in the Congo - but it was India, Ghana, which soon became independent and then of course the Nordic countries, his own country Sweden played a role. Ireland played a role.

So he always was very careful to bring into the picture the so-called middle powers or those below and he always defined the role of the UN ask speaking for those who otherwise would have no voice.

Carolyn:That was absolutely brilliant because he could be seen to be bringing in forces from countries who had absolutely no interest, no conflict of interest as it were, in the situation. Somebody from Ireland has no stake in what was going on in the Congo so it could be perceived as fair, as transparent. Brilliant! Just brilliant!

Henning:Exactly. And those countries realized it and for them he was their secretary general. Before I come to the whole history of the Congo, at the height of the Congo crisis, the Soviet Union asked him to resign. That was after the assassination of Lumumba. They were furious. They accused him basically of having been instrumental in the assassination of Lumumba. Maybe we can spend a little bit more time on that and the different takes on that. But he then resorted to a famous impromptu speech in the general assembly and you can still see it on YouTube.

So listeners who are now getting interested in the role of Hammarskjöld I can only encourage them to Google it up on YouTube and you will see in that live document how he was speaking in the general assembly where Hammarskjöld basically said

It's very easy for me to resign if any of the big powers ask me to do so. It's much more difficult not to resign. But as long as I have the support and the trust of those who are not the big powers I will stay in my office.At that moment he was interrupted by a standing ovation and you could see people like Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), Jawaharlal Nehru (India) standing up for a minute or longer and applauding him on that. Those people came from different camps during the Cold War. Even the allies of the Soviet Union from the third world countries were standing up and applauding the secretary general because he was their secretary general. Just before his untimely death there were tendencies that he really tried to give more weight to the general assembly to kind of reduce the decisive impact of the security council through the five permanent members with the veto power. He was not successful but one could see that he was never happy with that power structure and hierarchy.

He also very early said for him ECOSOC, the economic organ of the United Nations should actually be more important than the security council and he said so with reference to those nine countries that just entered independence, who inherited a colonial structure of their economy and stood absolutely no chance in terms of the global markets to emancipate themselves. So he very much was aware of that and he also used it in his diplomacy.

So now maybe is the time to move to the Congo if you are fine with that.

Harrison:Yes.

Henning:Well on that background I already mentioned he came up with an idea that the UN could only intervene in the Congo if the security council would play along, which was very difficult. That was in 1960, the height of the Cold War. Just keep in mind that was the time when the Berlin Wall was erected. Keep in mind that the two nuclear bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were fueled with uranium from the Katanga province. It was the time where the nuclear arms race between the Soviet Union and the USA was unfolding and a time where roughly 80% of the uranium supply for the US nuclear armament came from the Katanga province.

So the Congo was of utmost geostrategic importance of the time in 1960. And when it gained independence it very quickly turned into a crisis. And it was the then-prime minister Patrice Lumumba who approached the United Nations and asked for intervention to help him bring back the Katanga province into the Congo. The Katanga province which was declared a secession by Moise Tshombe with the support of the Belgians and the Belgian mining company Union Minière du Haut Katanga but also a lot of other mining companies of western countries. The Congo then already had the same relevance as it has until today. Maybe one of the third reasons why there was never peace in the Congo.

So only through the Tunisian representative in the security council of that time, Hammarskjöld managed to bring in a draft resolution which made it impossible for the permanent countries to prevent its adoption. But the draft resolution was pretty much watered down. It was a mandate which was so unspecific that it actually was no mandate because it only said that the UN should intervene in the Congo to reduce the violent conflict without intervening in domestic affairs. Now again, talk about a mission impossible. How to you manage to reconcile bringing peace to a conflict situation while at the same time you're not supposed to intervene in domestic affairs?

Hammarskjöld then in that situation actually tried to use it as an advantage because he later on said "This mandate is so vague that I can do a number of things and test them on the ground and if I'm criticized for that I can go back to the resolution and say "But the resolution is so vague, what else do you want me to do?" And that was the situation under which the UN sent the Blue Helmets to the Congo. Hammarskjöld went to the Congo on a fact-finding mission and he drafted while he was on the ground, an organogram on how the peacekeeping mission should look and it's quite amazing to compare it with the basic structure which has been in place for most of the last five decades. It's basically the same.

So already then he had a vision of how it should be with one very important thing which has been eroded a little bit since then. It was very clear that every United Nations mission was under the ultimate command of the secretary general of the United Nations meaning no one else would have the mandate to be delegated to execute anything on behalf of the United Nations which, as we know, happens in the meantime. But for Hammarskjöld it was very clear. It's him and his secretariats. They are in charge. They have the command.

What then happened unfortunately was that very quickly the situation eroded on the ground. Lumumba was ousted from the office and that was the first really tricky situation and huge problem for the United Nations because reinstating Lumumba could have been seen as an intervention into domestic affairs. And for that Hammarskjöld consulted his legal expert, Oscar Schachter and wanted to know what would be the interpretation of the mandate of the United Nations under the given circumstances. And the answer was that under the conditions of the constitution in existence, the President of the Congo had the authority to dismiss the Prime Minister if he was supported by at least one minister in the cabinet, which had been the case.

So after consideration Hammarskjöld and his advisors came to the conclusion that they would violate the mandate if they would now intervene to bring Patrice Lumumba into the office of the Prime Minister. Instead they offered him individual protection. Others called it house arrest. He was living in a house in Léopoldville and UN soldiers protected him. But it was very clear if Lumumba left that house to mobilize politically against the government, to basically bring himself back into the government, then the UN could not give him protection any longer because that would be an intervention into domestic affairs.

Patrice Lumumba on one night left the house. He was then captured. He was tortured and he was brutally murdered the first days of 1961 and there were a lot of people who accused Hammarskjöld and the UN of not coming to the rescue of Lumumba. Now what we know from a letter that Hammarskjöld wrote in February 1961 when the news was confirmed that Lumumba was killed under gruesome circumstances, a letter he wrote to John Steinbeck, that he was really sorry and in the letter he said "What a nightmare in stupidity because there is not anyone who will benefit from that". But up until today there are controversial discussions around that. There are a number of people who say Hammarskjöld was the agent of western interests and he cold-bloodedly sacrificed Lumumba for western interests.

Harrison:Henning, let me interrupt for a second because I want to read just a couple of sentences from Susan Williams' book.

Henning:Yes.

Harrison:I haven't talked about the book yet but it's called Who Killed Hammarskjöld, the UN, the Cold War and White Supremacy in Africa. It was published in 2011 and just on the subject of Lumumba, she said a couple of interesting things that I just wanted to bring up. I'll just read this short paragraph:

Just two months after the independence of the Congo on September 5th there was a new dramatic development facilitated by the CIA in Léopoldville. On the urging of Larry Devlin and with the support of Daffney Park, an MI6 official in Léopoldville, President Kasa-Vubu dismissed Lumumba and six other ministers, members of the democratically elected government.So right there I find it kind of sickening that Hammarskjöld would be blamed for what happened to Lumumba when the CIA and the MI6 had their hand right in it apparently. Right on the page before that Williams writes about Allen Dulles. She says,

When Dulles, the head of the CIA, heard about the arrival of Soviet assistance to Léopoldville...The Soviets had helped out Lumumba with some aid when he couldn't get it from other sources and so of course the US and the west were not happy about that.

...so Dulles sent an urgent telegram to Devlin [the CIA station chief] saying 'The removal of Lumumba must be an urgent and prime objective. This should be a high priority of our covert action.' The order had the authorization of President Eisenhower. Not long after Devlin was visited in Léopoldville by an emissary code named Joe from Paris who brought some deadly poisons to assassinate Lumumba. 'He handed over several poisons' wrote Devlin. One was concealed in a tube of toothpaste. If Lumumba used it he would appear to die from polio.So this is the kind of stuff that was going on right at the beginning there in 1960 and before Lumumba was assassinated. I just wanted to give that as a little extra context.

Henning:Yeah, I'm grateful for that important information. You're better prepared than I am speaking freely, and as the listeners now know this is not my mother tongue, so I'm offering apologies if my English is not always at the top but I hope that I come across in a way that what I want to say is understood. But you're absolutely right quoting those things. The Congo of 1960/61 - and that also then applies later when we discuss the circumstances of the plane crash - was a hotbed for western interests. You had mercenaries. You had the MI6. You had the CIA. You had all sort of unpleasant elements there and they were all ruthlessly following big power politics.

There were also to some extent Soviet interests but the Soviets never managed to get into the Congo to the extent they wanted to. That is where the critics of Hammarskjöld accused him of being pro-western because he was unable to intervene to bring an end to those western actors on the ground. But again, that's the dilemma of a UN secretary general who is bound by a mandate. That was of course then the flipside of this wait mandate which for the western interests could be exploited, they continued with destabilization politics. They continued to support Katanga. They assassinated Lumumba. Devlin wrote a book before he died and there are articles in Foreign Affairs these days which openly acknowledge that the assassination of Patrice Lumumba was the work of the CIA in collaboration with MI6. We know that and it's not the only one of its kind.

That was the situation on the ground. But as you rightly say, it would be very unfair and targeting the one person to give Dag Hammarskjöld the blame for that. He was frustrated immensely. What we know from some of the people around him, he was really angry and upset on some of the issues. One example was that in '61 for the election of the prime minster then, there was a candidate who was considered by the western countries as being close to the Soviet Union. The then president John F. Kennedy had already sent a message through the ambassador to Hammarskjöld saying if the UN allows that candidate to stand for elections the USA will have to consider stopping financial contributions to the United Nations. That only came up later on. One of the reasons was most likely because Kennedy himself was considered to be too lenient and he had to show that he was strict.

It's on record that Hammarskjöld got very angry and said to his confidante Esther Roux-Lanai who told the story. She said "We are not intervening in the domestic affairs. We stick to the mandate and to the Charter of the United Nations. And if the countries are not in line with that then it's for the countries to decide, but we are not giving in to such pressure." That's what I meant earlier by saying anti-hegemonic. He stood up not only against Soviet interests, he stood up against western interests.

It was this dilemma again of someone in charge of an operation where actually anything you did was limited by constraints by the situation of the Cold War on the ground. The other thing which we know in the meantime is of course it was not only Hammarskjöld. Hammarskjöld was surrounded by a number of people he trusted. They were the so-called "Congo Club". But some of them had very different views. What we know is for example, that Ralph Bunche, the very famous Afro-US-American who was also a Nobel Prize winner for peace, that he and Lumumba did not get along at all. The chemistry was basically toxic.

Lumumba was shocked to see that the US American working in the office of the Secretary General was black and in his views representing western imperialism. So he said "How can a black represent western imperialist interest?!" And for Bunche, Lumumba was unreliable, not strict enough, uncivilized. So actually when you read the documents of the interaction of those two, it's a nightmare! And anyone, including Hammarskjöld, had to rely of course on those operating on the ground and giving him feedback there. As far as we can establish, this so-called Congo Club did not always serve the right courses and purposes.

So at the same time they were under constant pressure. It was basically a stressful situation every day. There were situations where you had to make very quick decisions. You couldn't reflect properly. You couldn't think them through and that's of course exactly the situations where you tend to make mistakes. That was the situation then. And looking at it in retrospect, there are quite a number of people who are willing to give Hammarskjöld the credit but they said "Through his death he has failed to bring peace to the Congo. He might have failed even if he wouldn't have died. But what he managed was to prevent the Congo turning into the battlefield for the next Third World War."

I think that's a very important aspect to look at as well. You can look at the limitations of the Congo mission but you can also look at the achievements of the Congo mission. One of my favourite speeches of Hammarskjöld when he was under pressure was in the Security Council in I think May or June, 1961 where he was asked to resign, where he was criticized by the Soviet Union and the western countries - nobody of the influential countries trusted him - where he said in the Security Council "We managed to prevent the Congo being turned into a hunting ground for foreign interests". Now I love that statement. Which Secretary General since then would say something like that so bluntly?; to say "What we managed against all odds is to turn the Congo into a hunting ground for foreign interests".

And that was exactly what he tried to achieve and where he managed to achieve within the limitations, quite something.

Harrison:To approach the night of Hammarskjöld's death, he was on a plane to negotiate with Tshombe. Can you tell us why he was going there? What were the circumstances?

Henning:Yes. Now we come of course closer to the most interesting part of our conversation, isn't it? What happened was that in August and September of 1961 the situation on the ground had escalated to an extent that the local representative of the Secretary General, a maverick called Conor Cruise O'Brien, Irish, a firebrand - some afterward said it was a wrong choice by Hammarskjöld, but he was the one responsible for the local operations - decided that under the current circumstances, independent of the limitations of the mandate, the UN troops on the ground should try to chase the mercenaries out of Katanga through a military action and create the pre-condition that Tshombe has to give in and relinquish the secession of Katanga.

That was first done in an operation called Rumpunch in August '61, which originally caught everyone by surprise and was successful but then the UN troops, maybe in their naivety, were not careful enough to follow it up and they were driven out of Katanga again. And it was then followed around the 11th or 12th of September, by a second operation, Morthor. That was in a sense a turning point because the UN did what the mandate explicitly prohibited. The UN deliberately tried to intervene, even based on military intervention.

Hammarskjöld immediately after Rumpunch decided he had to go to the Congo. Before Operation Morthor was started we know that there were cables exchanged between Hammarskjöld, already in the Congo and again his legal advisor Oscar Schachter in the headquarters in New York. What they didn't know and we didn't know until last year was that in their communication on highly sensitive issues, Hammarskjöld was using an encryption machine for the cables for which the CIA and the MI6 had the codes. The manufacturer of the encryption machine, ironically a Swede who had relocated his factory to Switzerland, had also offered the western countries' secret services the means to immediately decipher the messages, the cables.

So the communication as we know it today between Hammarskjöld and New York and with everyone else, while he thought it was confidential, they already knew what he was communicating. And what we also know from some of the cables sent by diplomats on the ground, which were in archives and released after 50 years, was that the diplomats of the western countries, the British and the US on the ground, were very worried that Hammarskjöld in that situation, was meeting Moise Tshombe on neutral ground in Northern Rhodesia on an eye-to-eye basis without any other members of the parties involved participating, which means it's out of their control. And it seems possible that Hammarskjöld tried to achieve through those personal negotiations that Moise Tshombe would feel flattered because after all the Secretary General is willing to meet him, the leader of a secession, which brings us back almost 10 years to the situation in China, a representative of a force milieu on the ground which is not recognize international but recognized by the Secretary General, which makes such a person most likely more open to negotiations, and that he wanted to try to convince Moise Tshombe that being exposed to even the last consequence of the UN, is willing to apply force of arms to give in, to strike a deal, to bring back Katanga into the territory of the Congo and in return get one of the highest offices in the central government of the Congo.

Now the meeting never took place, as we know, because the plane crashed. But these were the indications that this might have been the likely agenda of Dag Hammarskjöld and that provided reasons for the western interests to be worried because re-integrating Katanga into the Congolese state territory would mean they would lose direct control over Katanga and through that, the direct control over the vast amount of natural resources with huge strategic importance. When Hammarskjöld left to meet Tshombe in Ndola in Northern Rhodesia, a border town in the copper belt of today's Zambia, border town to the Congo, he knew it was a dangerous mission. We know that Sture Linnér, one of his closest and most trusted collaborators from Sweden himself, was supposed to be onboard the plane, the Albertina, a DC-6 and Sture Linnér stated just a few years before he died that when he was supposed to enter the plane he saw that the feet of Hammarskjöld were shaking and Hammarskjöld took Sture Linnér aside and said "You just became a father. I want you to stay back on the ground". So Sture Linnér was sent out of the plane again, the plane that never arrived in Ndola.

The plane was flown by a secret route. It didn't fly a direct way to Ndola. It was flying a route without direct air contact, reducing it to the absolute minimum, to make sure that they minimized the risks of any unpleasant experiences in midair. Well the unpleasant experiences did happen when the plane was approaching Ndola in the night from the 17th to the 18th of December and while they already had radio contact with the tower in Ndola shortly before midnight on the night of the 17th to 18th December, the plane never arrived.

Now what we know today is there were a lot of people waiting on the ground for the plane to arrive, including the highest local British diplomat, including planes of the NSA which was already operational then, including a vast amount of mercenaries, including north Rhodesians who hated Hammarskjöld. The settler minority regimes in southern Africa did not like Hammarskjöld at all. That's a mild understatement because they considered him a secretary general of de-colonization, bringing black Africa to their borders. There were French and Belgians on the ground, you name it.

So when the plane did not arrive they switched off the lights at the landing strip and went home! It wasn't until the next morning that they started to search areas where the plane could have been. Now you don't need to be a brain surgeon when you listen to that to say "Really!?!? It was the plane with the Secretary General and 15 others onboard who had already contacted and said 'We are approaching the airport. We are about to land.' And then the plane does not arrive and everyone goes home or to their hotel and sleeps?!?!" That's the first thing which comes to mind of someone who looks at the matter and says "What was going on?!"

And the next thing was that officially the plane wreckage was only discovered the next day in the hours of the early afternoon. It was a few kilometres away! The wreckage was burning when it crashed. There were local African charcoal burners in the forest. They saw it crashing. They saw the fire. There were even - I say even because the charcoal burners were dismissed as unreliable witnesses by the locals because they were "only" Africans, uncivilized natives, not trustworthy because they wanted to besmear maybe the image of the whites. But there were also white people around who witnessed seeing the plane crashing. There were witnesses later on that testified they saw the wreckage the next morning but already the place was cordoned off and they were asked to move on.

So these are the first questions that make you wonder what was going on, on the ground. And sometimes people ask was that just amateurish behaviour by those who had to deal with the situation on the ground because they didn't know better or was it a deliberate cover up? I normally tend to answer most likely it was a mixture of both. But it was definitely I think not only amateurish. Whatever they wanted to cover up, which is difficult to clarify, led to certain behaviour which really caused a lot of questions afterwards.

I came across the local district searcher and he was then in his 20s. He was British. He was searching on the ground in the Kitwe copper belt district. When he was called to the plane - and I talked to him three years ago because he is still professor of tropical hygiene at the British University - when he was called to the plane crash on the ground, they said to him "Well you are officially in charge as the medical officer of the district of the investigations but we have someone from the Royal Rhodesian air force here who is familiar with this kind of accident. You'd better go on a holiday." And so he did.

I asked him three or four years ago, "Didn't you think that was funny?" And he looked at me and said "Well now that you ask, yeah, maybe." Those kinds of small stories come up left, right and centre when you look into what happened after 17 September 1961 on the ground.

Carolyn:You don't suppose it was hinted to him that it would be a very good idea if he took a holiday?

Henning: Well he's now in his 80s so I didn't want to investigate further. But he clearly did not feel comfortable when I insisted that this didn't make a lot of sense to me. Then he was reluctantly admitting "Yeah maybe, looking at it the way I do, it doesn't make a lot of sense."

Carolyn:Okay. Probably as far as he's willing to go.

Henning:Exactly.

Elan:You said that Hammarskjöld's legs were shaking before the flight and that suggested he may have had an intuition about how much danger he was in, which also suggests that he was incredibly brave and courageous in the midst of going on this mission. Do you think he had some idea as to what was being planned for him? Or was he just nervous?

Henning:Elan, I think of course he was nervous. I think everyone onboard was nervous, but I think he was pretty much aware of how risky that mission was. I don't think the Secretary General in our day would take such a personal risk. And it was the 15 others onboard the plane. It was not only him. If you follow some of his entries and markings and other statements or sentences he wrote down just a few weeks and months before that happened, you almost get a kind of weird feeling as if he somehow anticipated that his life might not last much longer. Now that sounds very funny but there are a number of really weird things that come up when you look into the circumstances.

Definitely the mission to Ndola was considered a high risk mission. It was most likely the general nervousness in such a tense situation as well as the awareness that this was not an easy task and that it also implied a personal physical risk. I'm pretty sure that was, yeah. I agree, he was extremely courageous and if you go back to his writings, that was the service he expected from himself. It was the service to humanity. It was the duty of his office. So basically he had to put his life on the spot to promote humanity, peace and the reduction of conflict. I think he truly believed in that.

Harrison:Henning, I just want to comment on a few of the things you mentioned about the night of the crash and the morning after. First of all is the presence of the mercenaries there. I think it was in the report that came out last year, the investigation into the new evidence about his death. It mentioned that there were 500 foreign mercenaries working in Katanga and among the mercenaries that were present at the Ndola airport that day were three in particular who had worked with a mercenary recruitment agency and one of these guys was Carlos Huyghé.

This guy was himself complicit in the assassination of Lumumba. Just to give a bit more context about the mercenaries there, in the months prior to the crash, they had assassination lists of UN personnel because the Katangese were basically at war with the UN and these mercenaries had assassination lists. It's not out of the ordinary to posit the idea that these guys were actually targeting UN officials and also the fact that the crash site wasn't found until 3:00 in the afternoon the next day and like you said, they turned off the lights and they all went home. That night when the plane didn't arrive right after, like you said, the top British diplomat in the region was there, the High British Commissioner in Salisbury, Lord Alport. He was the guy who had said "They probably just went elsewhere. They decided not to land here." So the people around him thought okay, he's a very prominent, authoritative figure so we'll just believe him". That's one explanation that's been given for why no one really did anything at that point because Lord Alport had very decisively said "He probably went elsewhere. They decided not to fly here."

Reading about Alport and reading some of the things he said - there are a lot of quotes in Susan Williams' book - and just from the quotes he comes across as the most pompous, arrogant guy imaginable. It just angers me to read the things he was saying and what he did that night.

Carolyn:It was the epitome of British colonial privilege. It's just disgusting.

Henning:You're right Carolyn. And thank you Harrison for bringing in some of the facts from Susan Williams' book. You and the listeners might realize I'm carried away when I talk about those things and I'm not pretending this scholarly distance where I would list just the factual evidence with the neutral words to back up what I think because I think one of the things is I've been engaged on the issues for too long to keep a neutral distance from the matters. Sue Williams' book really was a turning point because what she brought about was all the new initiatives that now have led to resolutions in the United Nations General Assembly to remain seized with the metal which is actually almost bordering on a fairy tale.

Her book Who Killed Hammarskjöld has in the title a question mark and she does not really answer the question and some of the evidence she has collected is in itself incoherent, if not even conflicting. But what she brilliantly achieves - and it reads like a John le Carré novel, only that it was a true story - what she brilliant achieves is that she brings to light all these inconsistencies, all these details. She also discovers new evidence and she points out all the things which at the end really make one wonder what truly happened. Despite the absence of a straightforward answer - as I said earlier there are far more questions than answers - and it really merits further investigation, even 55 years later because there are so many things that were not only amateurish, they would suggest it was a cover up.

Let me use one other example. The then very young person in charge of the Rhodesian investigation into the crash, was later in charge of the investigation of the plane crash of Helderberg, a South African plane which had an arms cache onboard which was then covered up as an accident and the very same person was in charge of the investigations of the aeroplane crash of which Samora Machel, the Mozambiquan President was onboard and died on South African ground.

The wreckage of all three investigations suggested that they were accidents. These are the kinds of coincidences where you don't really need to be a fan of conspiracy theories for you to really start wondering what was happening! And indeed, British diplomats on the ground were arrogant to such an extent that you say "What the hell!" They were rubbing shoulders with the white settler minority regimes and for them Hammarskjöld was a traitor of western civilization. Maybe they wouldn't say it like that as diplomats. Maybe they would only say it behind closed doors but it was very obvious that they could not relate to the approach of Dag Hammarskjöld to the issues in African societies and states.

Harrison:Henning, I want to give some background to the recent developments in the investigations leading up to Susan's book. Just to give some background, first of all there was the official investigation conducted by Northern Rhodesian officials and that was in 1961. It was then followed up by the official Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry and then the UN Commission. So all of these were going on in the months after the crash. I just want to read one little quote from Susan's book on the Rhodesian Commission. So this was the Northern Rhodesian Commission in the months afterwards. She says:

From the start the proceedings of the Rhodesian Commission had been based on the premise that the crash was an accident. 'At the outset we would say that no reason was suggested and we cannot think of one, why anyone who might have been able to attack this aircraft from the air should ever have wanted to attack it as it carried Mr. Hammarskjöld on the mission he was then undertaking.'When reading the book I just wrote next to it "Oh my god!" {laughter} because right there in the first commission they're saying "Why would you even think about it because Mr. Hammarskjöld was on there! Why would anyone want to kill him when he was on the plane?" which is just completely ridiculous especially in light of the new evidence. So that was like you said, just under 55 years ago when all these commissions had finally been finalized and the UN Commission couldn't come to any definite conclusions so it left open several possibilities just because they couldn't establish evidence for any of them so the options on the table were something like pilot error, some mechanical failure or an external attack or a hijacking. So they couldn't determine whether any of those had happened or not.

So things stayed like that until 2011 when Susan Williams published this book and that led to some very interesting developments. It led to - correctly me if I'm wrong - what was it called, the Hammarskjöld Report? Can you just tell us a bit about what happened after Susan's book and how that led to the latest UN resolutions?

Henning:I will gladly do so. Let me just add one minor thing to the story where you say "Why would one want to kill Hammarskjöld?" I can add "Why would one want to put an ace of spades into the shirt collar of Hammarskjöld while he was lying dead on the ground?" I've seen the photos. Now if someone didn't want to kill Hammarskjöld, why would someone put the ace of spaces next to the body on the ground? For those who might not remember that, that was the symbolic sign of those execution squads who were wandering around those days in Vietnam and somewhere else. They could have put the ace of spades next to him otherwise they wouldn't have burned him completely.

It was a clear, symbolic sign that some people around there did in a very cynical way, welcome that the Secretary General was killed in whichever way. And that highlights that he had more enemies than friends, especially in the western countries. So the one thing that was a blessing in disguise was that while the official UN Commission of Inquiry unfortunately followed most of the recommendations of the two Rhodesian inquiries and investigations, even as we know today through some papers that were released in the archives, were even willing to correct their report. Now listen to that! They were willing to correct certain statements in their report upon suggestions of British diplomats. We can prove that now. That's only a cable we discovered a couple of weeks or months ago.

So the UN investigation of '61 was willing to adjust their report because western diplomats wanted to rewrite the report. But the one thing they stopped short of was to buy into the pilot's error story as the excusing explanation. And they ended by saying they cannot exclude any of four possible reasons for the plane crash which included external influence or sabotage. And because of that, the general assembly of the United Nations when adopting a resolution on the basis of the report in 1962 decided that whenever there is new evidence, the United Nations has the authority to revisit the investigations and that was the entry point.

So when Susan published her book - and this is where the kind of fairy tale starts because it's one of those classic stories where individuals deciding rather spontaneously can at the end make a difference. That book was read by a member of the House of Lords in London. He was a former deputy minister and a trade union activist, not the typical aristocratic lord. He was the working-class lord based on his earlier marriage and he read the book. He didn't know Susan Williams and he reacted like you now do and others who said "What the hell was going on?!?!" So he said "We need to do something!" So he phoned Susan Williams and said "I read your book. We need to do something!" And Susan said "What do you want us to do?" And then he said "We've established an enabling committee" - which was what it was called - "and the enabling committee will try to establish a private investigation of Europe's legal experts with international reputations, to look at what you presented in your book to see how much of it substantiates further investigations."

So this handful of people was formed, in total seven people including another lord, including a former secretary general of the Commonwealth, including a former Swedish archbishop and two or three other people. I was one of them as well. We came together, no money, no connections and said "So what are we doing?" We scouted around and we approached four highly qualified international legal experts and asked them if they would be willing, on a pro bono basis because we had to money, to revisit the Hammarskjöld case.

Within a year we would find a part-time secretary of support for them. We would fund the necessary travels to Ndola for two of them and if they would be willing then in consultation with other experts, to just check to what extent all the evidence presented by Susan Williams in her book is water-tight and merits follow-upr investigations. And we got four highly qualified people. One of them was Richard Goldstone, the retired South African constitutional justice. The second was Hans Corell, a Swedish legal expert who was the undersecretary general for legal affairs at the United Nations before retirement. The third one was a high court judge from the Netherlands, Wilhelmina Thomassen and the fourth one was Sir Stephen Sedley, another lord who was a retired high court judge from the UK, also very distinguished, very professional.

A year later they submitted a report. We in the meantime had horrible difficulties to get the finances and I can mention it now because the one who provided most of the money most generously and at that time didn't want to be mentioned, was the late Henning Mankell, the famous Swedish author of these crime novels and other novels. He twice donated considerable money so that the commission could work properly and that we could fund the secretarial services of that person in support of the commission.

And after one year those four individuals presented a report which we made public without having seen it before because we needed to protect ourselves from accusations that we were trying to cook up something. We presented it in the international court in the Hague. The report was very measured, very modest, very meticulous in plain legal language but it clearly reached several conclusions which included that there were numerous local, credible African witnesses who were all systematically excluded from all of the previous investigations who were still alive and had, independently of each other, verifiable new evidence that has to be taken seriously, which points into the direction that there are strong assumptions that there was, when the plane was approaching Ndola airport, a second plane in the air.

And certainly the commission said they could establish the presence of the NSA on the ground and while they were stopping short of coming up with their own conclusion, they said "We think the evidence merits further investigation and we would strongly recommend that one of the entry points is to try to get access to the air traffic communication between the plane approaching Ndola airport and the tower at Ndola airport which with almost certainty was recorded by the NSA stationed with several planes at Ndola airport. Then they suggested on the basis of access to that air traffic communication one would maybe find further indications of what was happening in the last minutes or even seconds before the plane crashed.

That report was then handed over to the office of the Secretary General in October 2013 I believe, and Ban Ki-moon - who himself was very much inspired by Dag Hammarskjöld I must say, I've seen him twice speaking about Hammarskjöld also in Uppsala, visiting the grave and one could see he was deeply touched and moved personally by Hammarskjöld and the legacy. He in consultation with his team of experts then decided that this report of the independent commission merits recognition by the United Nations member states. So he sent out a circular to all member states where he announced that the report is translated in all official languages of the United Nations and that he will put on the agenda of the United Nations general assembly session that the report is discussed in the general assembly and his recommendation would be that the general assembly consider establishing a United Nations-established initiative to look further into the evidence available.

Then comes the next part of the fairy tale, or of the unforeseen stories because that happened in mid-2014 at the time when there was a conservative Swedish government. That Swedish government declared in the buildup to that - because we had mobilized on the ground in Sweden and other countries through different initiatives - had declared stubbornly to journalists and others, we were able to get interest in the case, that Sweden is not interested in reopening the case.

Now given the situation and how the United Nations operates, every other country we tried to mobilize said, if that agenda item is brought up in the general assembly session, if the Swedes are not taking the initiative, we are unable to do it because that's first and foremost a matter where the Swedes should stick out their necks and then we can support it. We can co-sponsor resolutions or draft resolutions but we cannot take an initiative without the Swedes taking an initiative.

So luckily I must say, that session until September passed and there were too many other more important things the general assembly had to deal with so that agenda item was never brought up in the general assembly. Then came September 2014 and elections in Sweden and from one day to the next, the government changed and we now have a Swedish government from the social democratic party and the green party and a foreign minister who was formerly our UN special representative Margot Wallström and she did a number of unexpected things. You might recall that she recognized Palestine, that she openly criticized Saudi Arabia. She did all sorts of things that made her not very popular in the west or in reactionary regimes.

One of the things the foreign ministry immediately said was "We want to have a follow-up on the investigations of the plane crash in Ndola". So when they agenda item finally was brought to the attention of the general assembly in early December of the year, the Swedish permanent representative tabled a motion in the general assembly with the support of more than 50 other countries co-sponsoring the motion, to say "We take the independent commission's report that seriously that we follow the suggestion of the Secretary General and we establish a small commission of experts tasked to look into the commission's report to verify if it is sufficiently credible for any further investigations."

So basically the UN will now properly check if the four legal experts were dreaming or if they have a serious case. That of course was a money problem. It took another two weeks or so to sort it out. Then the UN forked out of the military budget $500,000 US dollars, and appointed three experts - a retired chief justice from Tanzania who was the head of the expert commission, a ballistic expert from Denmark and someone who was a lawyer or legal expert from Australia - and those three were tasked within three months to verify the findings of the independent commission. They took only 10 weeks to submit their report which made some of us anxious that we felt "If they don't even use the three months, then we can't expect a lot from that expert commission's report."

But surprise, surprise! The three experts again did a very down-to-earth, meticulous job and eliminated some of the assumptions. They said "There remains sufficient doubt that there might have been a second plane in the air, that there is no credibility given to local witnesses that have not been considered before." They recommended that there be a follow-up investigation. That was brought again by the Secretary General to the attention of the general assembly, again with a recommendation that the general assembly might consider deciding in the resolution that further investigations be made and the experts also urged that an attempt should be made to get hold of archival material which was not release even to them as UN appointed experts should try to be gotten hold of. They mentioned deliberately the archives of the NSA, of the CIA and of MI6 and they attached two letters from the United Kingdom and the USA where both the legations to the United Nations explained to the expert commission that they are unable to release highly classified material even 54 years later because of national security interests. And the experts said "As long as you don't know what is in that material we cannot get closer to an explanation of what really happened on that fatal night."

So then came December last year, 2015 and the general assembly again had on its agenda the item of the Commission's findings of the experts and there was another draft resolution submitted by Sweden which again requested that if adopted that those certain countries - that's diplomatic parlance than you don't call them by name - that certain countries are urged to release the documents in their possession to bring more clarity to what really happened.

And that draft resolution as co-sponsored by more than 70 member states of the United Nations including - and that's most interesting - including Belgium, France and Russia. But those not among the co-sponsoring countries were the UK and the USA. And that resolution was then adopted by the general assembly and this is where we stand now. We basically have reached I hope not a dead end street, if I say so, but we have reached a point where the next question is "What on earth can we do to convince the USA and the UK to release the documents which we believe are in their possession which would offer more detailed indication of what really happened that night?"

And while we are talking, just this week the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon who really made it his personal matter, presented the annual Dag Hammarskjöld lecture in Stockholm which was organized by the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, and he repeatedly returned to Dag Hammarskjöld and the crash of the plane at Ndola and repeatedly urged that those countries should open their archives to allow us to establish in a better way, what happened.

But if that will happen, I don't know. Several people including journalists and media like the New York Times have already asked "What really happened then?" If they are willing to accept this egg on their faces not to release the documents, then that's of course the question they are inviting!

Harrison:Yeah. I've read a bunch on political issues, various controversies and it's amazing how many times those two words come up when the United States or Great Britain is confronted with releasing certain documents relating to these controversies and they say "Oh we can't release them because of national security." So it's gotten to the point for me where when I hear that I just automatically think "Okay, they must be guilty."

Carolyn:They must be.

Henning:That's of course the risk they take, yeah, absolutely.

Carolyn:Or they're just so arrogant they say "Well, you can think we're guilty but we don't care."

Henning:Well I'm not so sure. After all it was the UN Secretary General. That makes it really big. I mean Devlin had no problems to release in a book towards the end of his life, his involvement as a CIA agent and the involvement of Dulles in their assassination of Lumumba. We all know how often they did assassinate people. I'm sure there's a legion of assassinations we don't know about. But the killing of a secretary general, even if it might have been unplanned, in the sense that it was maybe a plane hijack or whatever, we don't know, but that makes it a really big thing. Who wants to be involved in the killing of the Secretary General of the United Nations and 15 others onboard the plane?

But that's the irony of it. By not disclosing the material in their possession they basically add fuel to the flames and they foster the suspicions that something was really going on then because otherwise why don't they open the archives.

Carolyn:Exactly.

Elan:And you know the downing of the plane is a story we've heard before. In 2003 or 2004 - I don't know if you've heard of this senator - we had a senator Paul Wellstone of Minnesota who was one of the few people - you can count them on one hand - who voted against going into Iraq and really riled up the ire of the Bush administration and a lot of the imperialist warmongering faction in the US.

Carolyn:Actually he was the key. He was the swing vote one way or the other. He held it.

Elan:A real thorn in the side of these people and his plane went down at some point and not two hours after the crash there were already intelligence agencies scouring the site. So it happened under very mysterious circumstances. It all points to this kind of mechanism for assassinating people who are calling justice or truth to power, still.

Henning:I didn't know that story. I must admit when it comes to US/American domestic affairs I'm as ignorant as a lot of US/American citizens if I may say with due respect, are ignorant when it comes to the rest of the world. But I'm not surprised to hear that story and I really don't think we have to be accused of cultivating conspiracy theories that this nourishes suspicions that something was not okay. That's a very common instrument which we in the west are not reluctant to apply when it comes to assassinations by the Russians. Then we take it for granted, "Yes of course the Russians kill people who are not in line with their interests". Well I'm sorry, I don't think there is a big difference in superpower behaviour, no matter where they come from. That is just how superpower is applied. And they have the means to do so. And unfortunately in many cases, they also have the means to cover up.

But it needs people like you folks who provide me with the opportunity to engage with you in that conversation and people like us in this enabling group and others, to take it out of the closet and say "Hello! Even if we don't know what happened, there is enough stuff to talk about and to make it an issue. It does not appear."

Another aspect is the human aspect. I know that for example, the family of those deceased, but especially the family of the pilot and the co-pilot, the sons, they have ever since 1961 lived with the assumption that the plane came down because of pilot error meaning their fathers and 15 others died because of an error of their fathers! I think there is a level also of human empathy that we owe it to those people who have lived ever since then with a kind of being blamed indirectly or feeling guilty for that, to say "Stop it! It's not that easy." And are refraining from taking the easy way out, blaming individual people and saying "Oh, it was controlled flight into terrain or it was the pilot's error."

That by the way is one of the concerns I have about a recent TV documentary that was broadcast by the National Geographic in its Mayday series. I understand it's a rather prominent series around airplane crashes and just a couple of weeks ago in several countries a new issue was televised called Deadly Mission and it deals with Ndola and the plane crash. It's a little bit over-dramatic but it comes to an end which is really not in line with what we know today I must say. And then again you ask yourself "Why are they so reluctant to call a spade a spade?" They pretend as if it was controlled flight into terrain and don't give sufficient credibility and recognition even to what has on the level of the United Nations been set and decided and what the Secretary General of the United Nations is saying!

Then again you start wondering without becoming paranoid, what kind of cover up can happen? Is it so unpopular that National Geographic is just not able to afford to put it in the way you would be able to put it on the state of affairs that is known to us now?

Carolyn:I think you can look on National Geographic as another propaganda arm.

Henning:Okay.

Carolyn:Truly. Truly. There's a lot of questionable information that gets propagated from that particular source and they have this great weight of history of being such a longstanding institution that people will buy it just because it was National Geographic.

Henning:Which is very unfortunate I must say. That's why I want to mention it because some of those listening out there, they might have, by coincidence, seen that when I saw it. I just warn them have a close look, but be very careful, especially when it comes to the end, when first those suspicions are introduced but only at the end to be dismissed again.

Carolyn:But they're still planted.

Henning:Yeah.

Carolyn:Yeah. It's classic.

Harrison:Henning, there were a few details I wanted to share about the latest UN report which came from the Hammarskjöld Commission Report that you guys did. First is the topic of the NSA and the CIA. One of the bits of evidence that Susan puts in her book and which was investigated in these two venues was the report of an NSA employee who was stationed at the NSA base on the island of Cyprus.

Henning:The late Mr. [Charles] Southall, yes.

Harrison:Yeah. Apparently he told numerous people before he told Susan Williams, but the story's in her book, how he was stationed there and the evening of September 17th he got a call from someone else at the base saying "You better come over here because something big is going to happen". So he went down and he says that when he got there he either heard or read a report - he wasn't quite sure in his memory - that was a firsthand report that sounded like it was coming from a pilot saying "Okay, I've got the DC-6 and I fired and it's going down" or something like that. And he heard this report and it was seven minutes after the incident.

Then there was another person Abrams, I believe...

Henning:Yes.