© Jewel Samad/AFPThe new Central Union Mission shelter in Washington, DC

The final week of January saw an annual ritual in government statistical gathering that few people know about — the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Point-in-Time survey of the homeless population, in which HUD recruits volunteers around the country to go out and try to count up all the homeless people living in America. This year, White House Chief of Staff Dennis McDonough even joined up,

volunteering as part of the San Francisco PIT crew.

Counting the homeless is, of course, a critical element to making appropriate homelessness policy. But

good policy also requires greater awareness of a discovery that research continuously confirms — it's cheaper to fix homelessness by giving homeless people homes to live in than to let the homeless live on the streets and try to deal with the subsequent problems.The most recent report along these lines was a May Central Florida Commission on Homelessness study indicating that the

region spends $31,000 a year per homeless person on "the salaries of law-enforcement officers to arrest and transport homeless individuals — largely for nonviolent offenses such as trespassing, public intoxication or sleeping in parks — as well as the cost of jail stays, emergency-room visits and hospitalization for medical and psychiatric issues."

By contrast, getting each homeless person a house and a caseworker to supervise their needs

would cost about $10,000 per person.

This particular study looked at the situations in Orange, Seminole, and Osceola Counties in Florida and of course conditions vary from place to place. But

as Scott Keyes points out, there are

similar studies showing large financial savings in Charlotte and Southeastern Colorado from focusing on simply housing the homeless.The general line of thinking behind these programs is one of the happier legacies of the George W Bush administration. His homelessness czar Philip Mangano was a

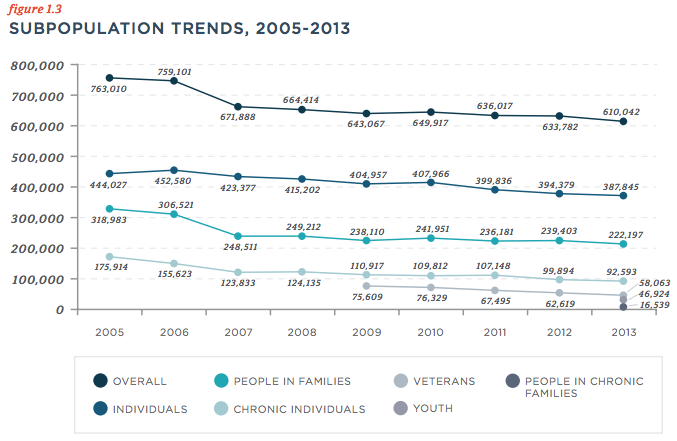

major proponent of a "housing first" approach to homelessness. And by and large it's worked. Between 2005 and 2012,

the rate of homelessness in America declined 17 percent. Figures released this month from the National Alliance to End Homeless

showed another 3.7 percent decline. That's a remarkable amount of progress to make during a period when the overall economic situation has been generally dire.

© Source: National Alliance to End Homelessness

But the statistical success of anti-homelessness efforts even in the face of a bad economy underscores the point of the Florida study.

When it comes to the chronically homeless, you don't need to fix everything to improve their lives. You don't even really need new public money.

What you need to do is target those resources at the core of the problem — a lack of housing — and deliver the housing, rather than spending twice as much on sporadic legal and medical interventions. And the striking thing is that despite the success of housing first initiatives, there are still lots of jurisdictions that haven't yet switched to this approach. If Central Florida and other lagging regions get on board, we could take a big bite out of the remaining homelessness problem and free up lots of resources for other public services.

"...if there is a concerted effort and willingness to do so." Which isn't the case... the PTB have to maintain control by division, and what better way to control those with a decent living than surround them with those without one? It adds the necessary touch of fear for herd control as well.