"Why is the university silent? Why are the professors silent?" Rouhani said. "What are you afraid of?"

One answer may be that they were afraid of being jailed, suggests Anna Maryam Rafiee, a cultural heritage specialist in Toronto, Canada. Her father, chemist Mohammad Hossein Rafiee, has been stuck in a cell in Iran's notorious Evin Prison since June 2015, after speaking out in favor of the nuclear deal that was announced a month after he was imprisoned.

Now, more than 300 scholars and scientists, including seven Nobel laureates, have signed an open letter calling on Iran to release Rafiee. "Restricting Dr. Rafiee's rights to freedom of expression through arrest and detention, the conditions of his prosecution, and his inhumane conditions in Evin Prison represent violations of both the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to which the Islamic Republic of Iran adheres," the 27 January letter says. Numerous organizations, including Amnesty International and the American Chemical Society, are also calling for the release of the chemist, and the U.S. government has said he is a political prisoner.

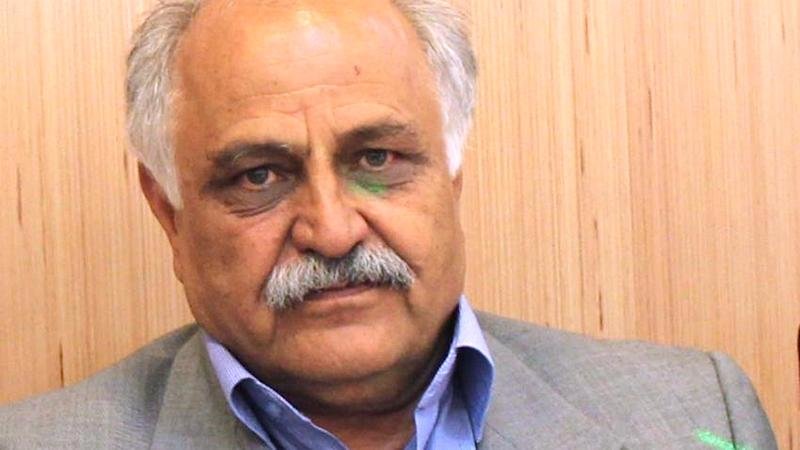

More than a year before the nuclear deal was finished, Rafiee, a retired professor from the University of Tehran, had written an analysis that supported the negotiations. He sent his 120-page paper to the Iranian government. Then, in June 2014, he spoke out publicly, publishing his analysis on his website.

That's when the harassment began, his daughter tells Science Insider. "On June 30, 2014, the [Iranian] intelligence ministry raided our house," she says. "They tried to find something in our house to use against my father in the court." Rafiee was ultimately arrested—"kidnapped in the street by intelligence agents," Anna Maryam Rafiee says. After a secret trial, she says her father was sentenced to 6 years in prison for "spreading propaganda against the regime," as well as "membership in an illegal group," known as the Melli Mazhabi, a part of the Freedom Movement of Iran.

Her dad has described the prison as a "torture chamber," Anna Maryam Rafiee wrote last year in The Guardian. He was sleeping on the floor, she wrote, because his cell didn't have enough beds for the 28 prisoners in it.

Prison officials did not allow Rafiee to attend his most recent court hearing, says his daughter. "According to the judge, my father could be released on bail" during his appeal, she says, but that hasn't happened.

This was not Rafiee's first brush with Iranian authorities. He was arrested in 2000 for being a member of the Melli Mazhabi, and sentenced to 4 years in prison, which he never served.

Comment: The Melli Mazhabi is the Freedom Movement of Iran.

Rafiee's imprisonment reflects Iran's perilous internal politics, says one of the letter's signers, chemical engineer Muhammad Sahimi of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Rouhani's request for academics to speak up in favor of the nuclear negotiations was "sincere," Sahimi tells Science Insider. But "Rouhani does not control the judiciary and the intelligence unit of the IRGC [Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps]," a more hardline group in Iranian politics.

Rafiee "and his comrades have always been under tremendous pressure by the hardliners in Iran, because they know that the [Melli Mazhabi] is appealing to university students and other strata of the Iranian society," Sahimi adds. The group, he asserts, is "squeaky clean."

Representatives of the Iranian government in the United States declined to comment on the case. (Iran hasn't had its own embassy in the United States since 1980.) "I don't know. I'm not familiar with it. I can't say anything about it," says Fariborz Jahansoozan, who works in the legal affairs department of the Iranian interests section of the Pakistani Embassy in Washington, D.C. (He did say that science is "important for the country.")

"We would consider [Rafiee] to be a political prisoner under these circumstances and would call for his release, as we do for other political prisoners in Iran," said an official with the U.S. State Department, in a statement provided to Science Insider.

Anna Maryam Rafiee, meanwhile, says her father's case could have long-lasting implications. "I wonder who will trust President Rouhani," she wrote in The Guardian, the "next time he puts out a call for Iranian intellectuals and academics to rally behind him."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter