A new study appears to show that the devastating disorder is linked to a physical process where connections between parts of the brain are "pruned" away.

The finding could lead scientists to be able to work out a way of treating the disease at its source, rather than simply looking to reduce the symptoms. It might even be discovered that schizophrenia could be triggered by an infectious agent.

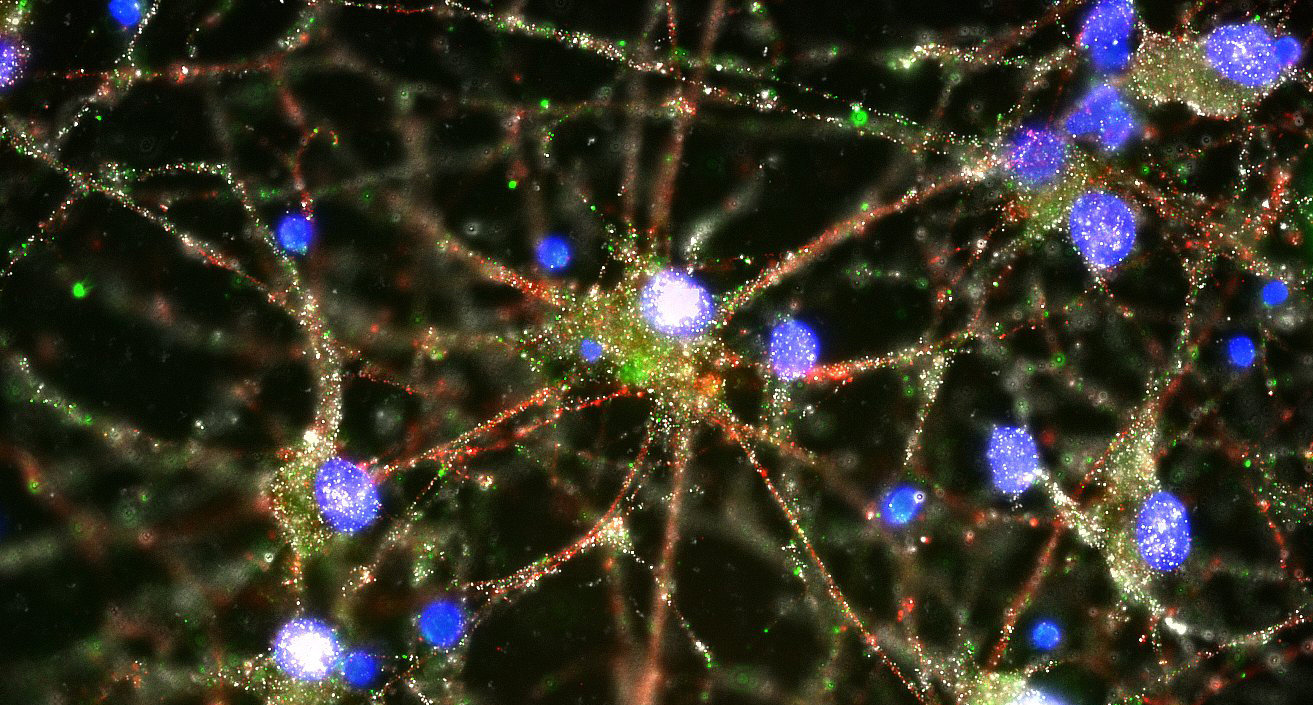

When people are going through adolescence, their brains are re-wired in a way that sees some synapses cut away. But a gene leads some people's brains to prune away too much, and leads to presentations of schizophrenia, according to the study.

The extreme "pruning" can bring about the symptoms of schizophrenia, which can be hugely debilitating and lead people to lose their grip on reality and see delusions and experience paranoia.

Lead researcher Dr Steven McCarroll, from Harvard Medical School in the US, said: "Since schizophrenia was first described over a century ago, its underlying biology has been a black box, in part because it has been virtually impossible to model the disorder in cells or animals.

"The human genome is providing a powerful new way in to this disease. Understanding these genetic effects on risk is a way of prying open that black box, peering inside, and starting to see actual biological mechanisms."

The gene is called C4. It is an important part of the immune system, and finds infectious microbes — which has led scientists to wonder whether schizophrenia might be triggered by one of them.

The findings, reported in the journal Nature, could explain why schizophrenia usually strikes during late adolescence.

Brains of people with the disease also tend to have a thinner cerebral cortex, the outer layer of neural tissue that processes sensory information and plays a key role in thinking and consciousness, with fewer synapses, or connections.

Dr Bruce Cuthbert, acting director of the US National Institute of Mental Health, who was not one of the study authors, said: "This study marks a crucial turning point in the fight against mental illness.

"Because the molecular origins of psychiatric diseases are little-understood, efforts by pharmaceutical companies to pursue new therapeutics are few and far between.

"This study changes the game. Thanks to this genetic breakthrough we can finally see the potential for clinical tests, early detection, new treatments, and even prevention."

The discovery, which follows five years of detective work, involved detailed analysis of more than 65,000 complete human genetic codes and the examination of brain samples from hundreds of deceased people, as well as animal tests.

It raises the possibility of future therapies that reduce synaptic pruning in people showing early symptoms of schizophrenia.

Current treatments aim to alleviate the condition's terrifying symptoms but do not address its causes.

Co-author Dr Beth Stevens, from Boston Children's Hospital in the US, said: "We're far from having a treatment based on this, but it's exciting to think that one day we might be able to turn down the pruning process in some individuals and decrease their risk."

British expert Professor Mike Owen, director of the Medical Research Council Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics & Genomics at Cardiff University, said: "The possibility that excessive synaptic pruning plays a role in schizophrenia has always been intriguing but largely unsupported by convincing evidence.

"But these findings change that, and might also help explain why the symptoms of schizophrenia tend to become manifest in adolescence and early adulthood when synaptic pruning is taking place.

"New research will be needed to understand exactly how C4 plays a role in synaptic pruning and schizophrenia and how this process interacts with other genes and proteins that have been implicated in the disorder.

"Treatment implications are unclear at the present time but this new work points the finger at a particular process and implicates a set of potential new targets which will need to be explored in experimental systems."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter