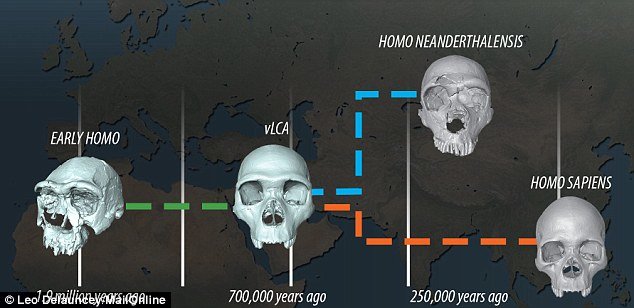

Now, researchers have used new digital techniques to recreate the skull of the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals for the first time.

It reveals how we split the human-Neanderthal lineage split about 300,000 years earlier than thought.

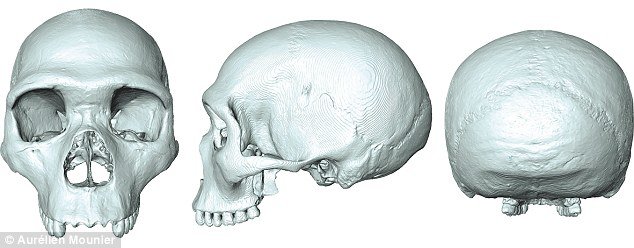

The skull also shows how our ancient forefathers had human cheekbones, but a Neanderthal-like bulge at the back of the skulls.

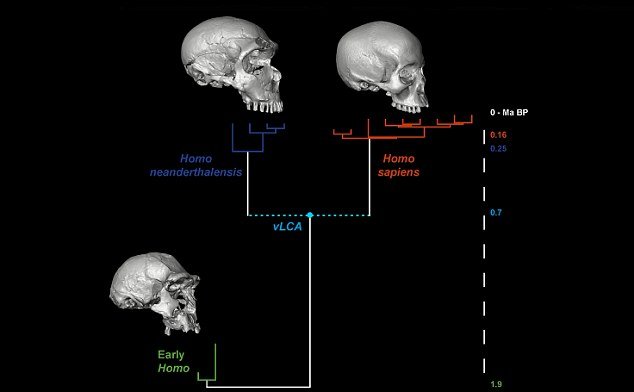

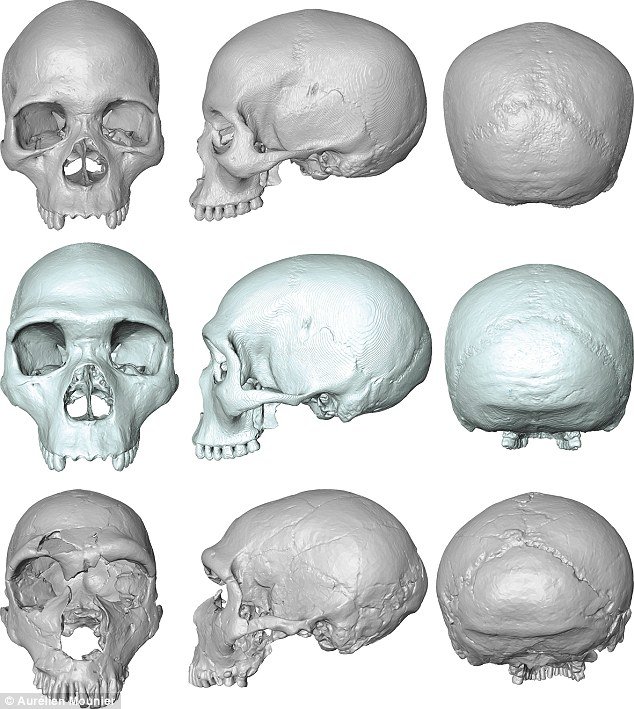

The 'virtual fossil' has been simulated by plotting a total of 797 'landmarks' on fossilized skulls stretching over almost two million years of Homo history.

These skulls included a 1.6 million-year-old Homo erectus fossil, Neanderthal crania found in Europe and a 19th century skulls in Cambridge.

They then fed a digitally-scanned modern skull into the timeline, warping the skull to fit the landmarks as they shifted through history.

This allowed researchers to work out how the morphology of both species may have converged in the last common ancestor's skull during the Middle Pleistocene.

This was an era dating from approximately 800,000 to 100,000 years ago.

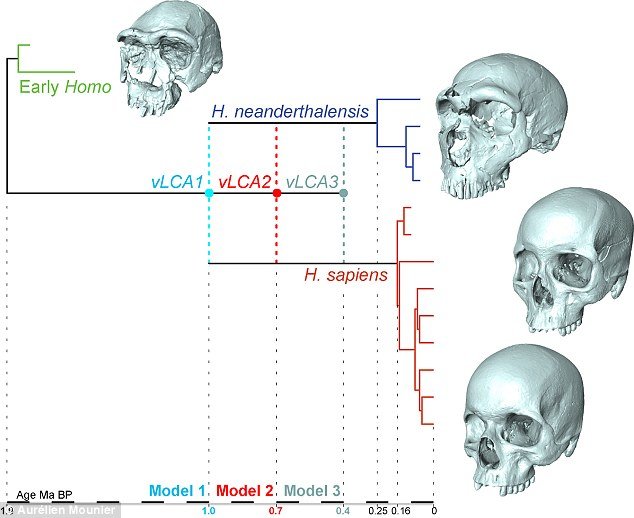

The team generated three possible ancestral skull shapes that matched up with three different predicted split times between the two lineages.

They digitally rendered complete skulls and then compared them to the few original fossils and bone fragments of the Pleistocene age.

This enabled them to narrow down which virtual skull was the best fit for the ancestor we share with Neanderthals, and which timeframe was most likely for that last common ancestor to have existed.

Previous estimates based on ancient DNA predicted the last common ancestor lived around 400,000 years ago.

But results from the 'virtual fossil' show the skull morphology closest to fossil fragments from the Middle Pleistocene suggests a lineage split of around 700,000 years ago.

It also found that - while this ancestral population was also present across Eurasia - the last common ancestor most likely originated in Africa.

The details of its dispersal from there, however, are still debated.

A study in October suggested that our ancestors first spread east, via the Arabian Peninsula, and entered South Asia long before the 60,000 year mark.

This conclusion was made by studying 47 human teeth from a cave in southern China.

Scientists excavating an area in Daoxian said the fossils belong to modern humans and date to at least 80,000 years ago.

This contradicts the theory Homo sapiens didn't move eastwards until 60,000 years ago instead settling around Eurasia.

Most scientists believe that our species appeared in East Africa around 190,000 to 160,000 years ago.

After this, human fossils from the archaeological sites of Es Skhül and Jabel Qafzen, in Israel, suggest they spread there between 80,000 and 120,000 years ago.

Fossil evidence suggests they arrived in Europe 60,000 to 40,000 years ago.

But the new samples suggest some early humans 'on verge of modernity' may have migrated to southern China.

Scientists also suggest that that modern humans, who started out in Africa, weren't prepared from the harsh winter conditions in Europe.

The results of the virtual fossil study are published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

'This allowed us to predict mathematically and then recreate virtually skull fossils of the last common ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals, using a simple and consensual 'tree of life' for the genus Homo,' said Aurélien Mounier, a researcher at Cambridge University's Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies (LCHES).

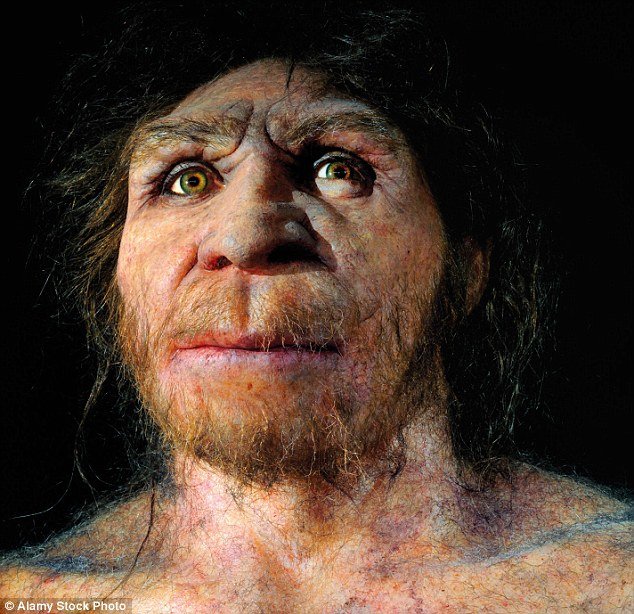

The virtual 3D ancestral skull bears early hallmarks of both species.

For example, it shows the initial budding of what in Neanderthals would become the 'occipital bun': the prominent bulge at the back of the skull that contributed to elongated shape of a Neanderthal head.

But the face of the virtual ancestor shows hints of the strong indention that modern humans have under the cheekbones, contributing to our more delicate facial features.

In Neanderthals, this area has thicker bone due to more air pockets, so that the face of a Neanderthal would have protruded.

Research from New York University published last week showed that bone deposits continued to build on the faces of Neanderthal children during the first years of their life.

The heavy, thickset brow of the virtual ancestor is characteristic of the hominin lineage, very similar to early Homo as well as Neanderthal, but lost in modern humans.

The population of last common ancestors was probably part of the species Homo heidelbergensis in its broadest sense, says Mounier.

This was a species of Homo that lived in Africa, Europe and western Asia between 700,000 and 300,000 years ago.

For their next project, Mounier and colleagues have started working on a model of the last common ancestor of Homo and chimpanzees.

'Our models are not the exact truth, but in the absence of fossils these new methods can be used to test hypotheses for any palaeontological question, whether it is horses or dinosaurs,' he said.

the coming of todays world

[Link]