The concept of a spiritual afterlife connects cultures across time and around the world. The idea of a ghost—the spirit or soul of a dead person that returns from the grave and connects the living—has been part of human belief systems from the beginning. Ancient writings told of ghosts, ranging from deceased and beloved family members, to ominous harbingers, and the evil specters who terrorized or killed.

Known by countless names such as: phantom, wraith, spook, shade, and poltergeist, ghosts are thought to stem from the beliefs of animism (that all things possess a spirit) and ancestor worship in the earliest cultures. The idea that the spirit survived death and the veneration of the dead, was a central part of ancient religions, no matter the society. Reasons why a soul or corpse would wander depended upon the 'rules' of death and the afterlife as established by a culture.

Headache? Blindness? Mental Disorder? You've Seen a Mesopotamian Ghost

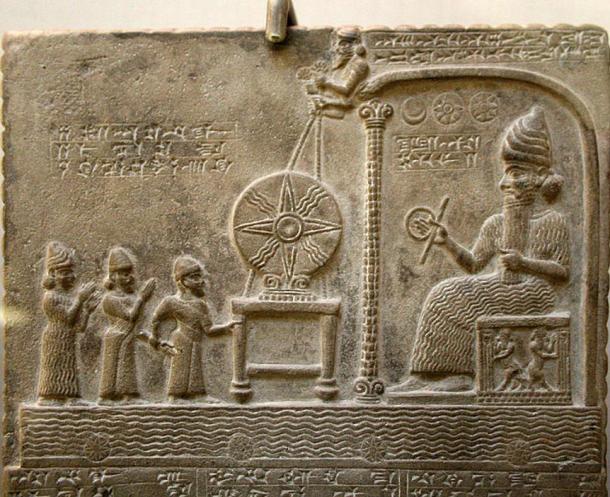

In the ancient religions of Sumer, Babylon and Assyria, ghost of the deceased were called gidim or etemmu. At death, the ghosts would retain their personality and memories of their lives, and travel to a netherword ruled over by the dark queen Ereshkigal. Mesopotamian gods, the Anunnaki, would decide the fate of the soul. While it was believed there were dangerous beasts and demons in the netherworld, ghosts could live peacefully in afterlife houses, greeting old friends and family. They would be allowed to return to the living if they needed to complete a mission or right a wrong.

Ghosts who haunted the living without permission were said to be punished by the sun god Shamash.

There were various methods to cure the maladies caused by ghosts: exorcisms, ritual burials, amulets or charms, salves, potions, and even suppositories. It was felt that if relatives provided good food and gifts in ancestor worship, it made the afterlife more tolerable for dead spirits, and they would stay where they belonged—in the netherworld.

A Heavy Heart is a Fate Worse than Death in Ancient Egypt

As long as the body was properly prepared and buried with the appropriate rites and continually remembered, the spirit would rest well. If any of these conditions were not met, it was believed the ghost would walk the earth and wreak havoc, causing nightmares, feelings of guilt, or illness.

It was only in relatively modern times that the idea of disturbing Egyptian tombs would result in an angry, shuffling, undead mummy.

Ancient Romans Summoned Ghosts to Haunt Their Enemies

In the fifth century BC ghosts took on a more frightening aspect, and could be either good or evil. They were thought to haunt the immediate area of their corpse, and so cemeteries became places where the living didn't linger. Fortunately, it was said that ghosts would only appear in a room lighted by a torch, as some kind of light was necessary to see them.

Ghosts who visited the living in dreams were just reaching out to loved ones, and these visitations were not the same as restless ghosts who had died untimely or unjustly.

To stave off hauntings, the dead were ritually mourned in public, with annual feasts honoring the spirits. After elaborate public offerings and libations, the ghosts were then instructed firmly to "leave until the same time next year."

By scratching a curse on a piece of lead or pottery, and placing it in a grave, ancient Romans believed ghosts could be summoned and compelled to exact punishment on an enemy.

Several writers of antiquity recorded ghost stories, such as Plutarch in the first century AD. He chronicled the story of a haunted bath house that would echo horribly with the undead screams of a murdered man. The noises got so terrifying the people of the town sealed up the doors of the building. In 50 AD historian Pliny the Younger recorded a tale of a ghost in chains who only rested once his shackled skeleton was dug up and properly reburied.

Dismal Afterlives Spent in Purgatory

By the Middle Ages in Europe, ghosts were considered no trifling matter, and often believed to be the work of demonic forces which were heavily battled by the church. Ghosts were either souls returned to earth for a specific purpose, or they were evil spirits with a singular aim to terrify or tempt the living. To tell good and evil apart the living could demand to know the ghost's purpose "in the name of Jesus Christ", whereupon the evil ghost would be banished by hearing the holy name.

These ghosts could present themselves in many ways, from insubstantial mist that could move through walls to fully-formed physical bodies that one could touch—although ghosts were almost always male in reports. They were usually described as paler and sadder than their living forms, and dressed in rags. This dismay should not have been surprising, as it was believed most ghosts were assigned to Purgatory, a temporary spiritual plane of purification that was neither heaven nor hell, where souls would stay for as long as it took to atone for any sins or transgressions during their life.

Ghosts were said to take the form of combative knights in armor, and entire ghost armies were reported fighting epic battles at night.

It was thought that evil ghosts could be banished by holy word or exorcism by priest, and good ghosts would return to the afterlife once their purpose had been fulfilled.

Celtic and Ancient European Undead Walk the Earth

Many people have heard of the Banshee creatures of Celtic lore—women who had died prematurely and whose screams of grief portended a death, and there are numerous other ghosts who cross the lines between the afterlife and the realm of fairies.

Ghosts certainly plagued the dead in ancient Celtic tradition, but the cyclical, wheel-like nature of their beliefs meant that there were times during the year when one was more likely to be visited. The dead were thought to leave the afterlife and walk freely during Samhain, or "summer's end", (late October, early November).

Comment: For more background information on the global customs and celebrations in late October and early November, see: Witches, Comets and Planetary Cataclysms

The living would prepare feasts for the ghosts of friends or family, livestock was slaughtered for the oncoming winter and the bones were burned on a massive fire. As such, bone fires became "bonfires". To elude the restless or evil ghosts, the living took to wearing masks so they would not be recognized by the supernatural. This practice eventually lead to the modern Hallowe'en tradition of dressing up and wearing disguises.

Scandinavian tradition held many specific rites and ceremonies in order to ensure the living weren't plagued by undead spirits of fallen warriors or beloved relatives.

Ancient Norse beliefs of ghosts included the mythology of the draugr, an undead creature, literally meaning "again-walker". Not unlike modern zombies of popular culture, the draugr was risen decomposed body that would seek out and attack those who had wronged it in life.

Traditionally, iron scissors were placed on the chest of the recently deceased, and twigs tucked into their clothing. Gruesomely, needles would be driven into the soles of the feet to prevent walking, and their toes were tied together. The 'corpse door' was considered the most effective deterrent - a special door was built and the body was passed through. People surrounded the corpse as this was done to confuse and disorient the spirit of the departed, and then the doorway would be sealed up to prevent a return.

Read more in PART II.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter