Last week, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) joined the ever-more vocal debate on antibiotic resistance, calling on GPs, nurses, pharmacists and dentists alike to rein in inappropriate prescription practices.

According to the institute, 10 million prescriptions for antibiotics are dished out unnecessarily every year, despite - in the words of NICE Director of the Centre for Clinical Practice Professor Mark Baker - "knowledge amongst GPs that many patients ... do not require and will not benefit from antibiotics."

This intervention is welcome, as are NICE's newly published guidelines which set out recommendations for the responsible use of antibiotics. The resistance problem is (as we are frequently told by experts including the Chief Medical Officer and WHO officials) set to shake the very foundations of modern medicine.

We must implement every measure possible to safeguard our drugs for future generations, and as overuse of antibiotic in human medicine is the principle driver of resistance in humans, this is a sensible place to start.

Farms emerge as a major engine of drug resistance

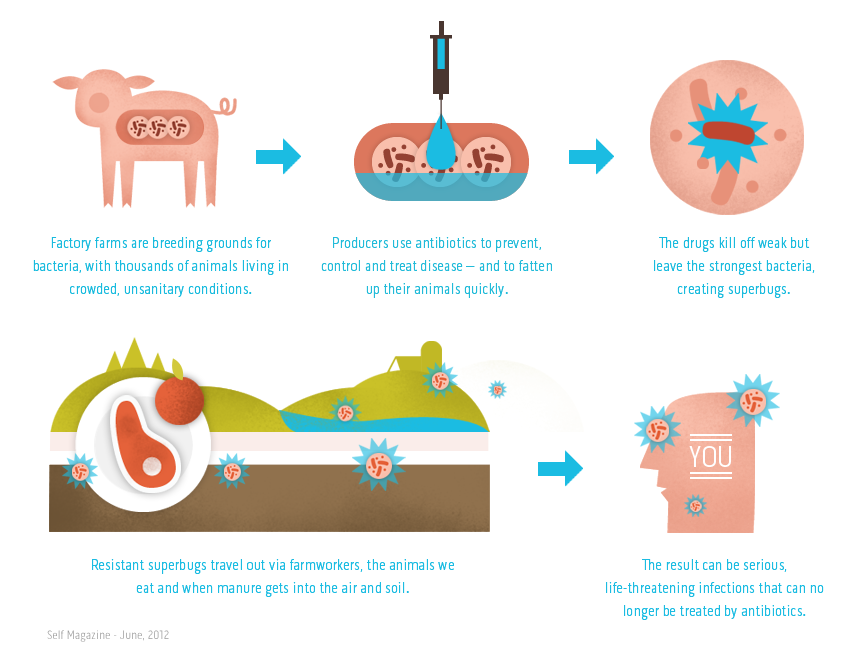

However, there is a crucial area that we cannot afford to overlook if we are to have a chance of truly tackling this issue: systematic overuse of antibiotics in farming. Farm animals account for almost two thirds of all antibiotics used in 26 European countries and for approximately 40% of total usage within the UK.

There is a broad consensus of the association between antibiotic consumption in animals and resistance in human infections. For some bacterial infections such as Campylobacter, Salmonella and E. coli, farm antibiotic use is a key cause of resistance.

Emergence of resistance to antibiotics classed as 'critically important' for humans is a major recent development, driven in part by inappropriate use of these drugs in farming.

Yet antibiotic use in farming tends to be overlooked. One reason is that farm antibiotic use falls firmly within the scope of Defra, with comparatively little involvement from health officials in the formulation of policy in this area.

The Government's five year AMR Strategy provides an example of this siloed approach. It fails to include measurable targets for reductions in farm use, despite including targets for use in human medicine. GPs are urged to take action, yet veterinary prescribing practices escape scrutiny.

This dichotomy is a curious one. Misuse of antibiotics in farming is a public health issue. The implications are already being felt by the very healthcare professionals exhorted to curb their prescribing practices.

Within the EU, human infections such as MRSA are being traced back to the farm, and the costs of human resistance from profligate of drugs in farming will increasingly be felt by the NHS.

Professor Baker states that handing out drugs to patients which are unlikely to do the patient any good "is not good practice". This comment throws current on-farm prescribing practices into sharp relief.

Over 85% of UK farm antibiotic use is for mass medication

Antibiotics are routinely given to healthy animals - in the knowledge that they will not do the animals any 'good' in the therapeutic sense. What they will do is to increase the rate at which many animals put on weight, increasing farm profitability.

Within the EU it is legal to routinely treat animals which do not require treatment as a purely preventative measure - an insurance against potential disease outbreaks. In the UK over 85% of farm use is for mass medication.

Farmers may even use the critically important drugs. Whilst medical use of these drugs has declined over the last eight to ten years in the UK - thanks to the hard work of our health professionals - farm use has increased by 35% in last four years.

Sick animals must, of course, be treated. Groups of animals in which there is some incidence of disease may need treatment to avoid contamination. But routine, purely preventative dosing of healthy animals flies in the face of any rationale behind responsible use, and exposes the targets directed at prescribers of human medicine as disintegrated, incoherent and potentially ineffectual.

Why are the principles around 'responsible' antibiotic use in human medicine considered less salient when applied to animal medicine?

There appears to be an easy justification: if we do not preventatively treat livestock, disease outbreaks risk impacting welfare and farm profitability. This is indeed the case in intensive systems, where animals are typically kept together indoors in confined spaces, conditions which linked to respiratory diseases and infections such as swine dysentery.

Farm use of antibiotics must be tightly regulated

Dr Ron Daniels, Chair of the UK Sepsis Trust, provides a disconcerting analogy:

"Within my intensive care unit that unit, we look after 12 patients treated in isolation. If we changed our system to look after 50 or 100 patients within that same footprint, patients would start to share their bacteria and we would find the spread of resistant bacteria between those patients very quickly."Whatever your views on intensive farming, the rationale behind prophylactic use of drugs to groups of healthy animals becomes increasingly questionable as the link between farm use and human resistance grows stronger.

Whilst official policy tells us that such routine use is insupportable, lack of clear guidance on antibiotic usage in animal medicine is putting our health at risk. The VMD, responsible for antibiotic use policy within the UK, has stated that

"prescribing practices are known to vary between veterinary surgeons depending on experience, information available and degree of risk considered acceptable."We urgently need standardisation of farm use of antibiotics, in may take the shape of a coherent policy to phase out routine, prophylactic mass-medication, and dramatically reduce use of the critically important antibiotics.

In human medicine, pushy patients may indeed make things tricky. But in some ways the role of the vet is more complicated than that of the medical doctor: they must contend with the patient - the animal, as well as the client - the owner. Clear regulation is crucial to ensure that pressures are not brought to bear on prescribing decisions.

The medical community must add their voice to the call for measures to save antibiotics for use in unhealthy humans, not in healthy animals. Lack of action risks undermining any progress made in human medicine, and failing to halt the spread of antibiotic resistance which will render our precious drugs useless.

About the author

Emma Rose is Campaign, Communications and Lobbying Specialist for the Alliance to Save our Antibiotics - a coalition of health, medical, animal welfare and NGO organisations, supported by the Jeremy Coller Foundation.

Comment: The SOTT page has been covering the issue of factory farms and antibiotic resistance for the past several years and yet nothing has really changed. As the article states above; 'Why are the principles around 'responsible' antibiotic use in human medicine considered less salient when applied to animal medicine?'