In 2005, DuPont settled a class-action lawsuit brought on behalf of 70,000 mid-Ohio Valley residents for decades of fouling their drinking water with a highly toxic chemical once used to make Teflon. As part of the settlement, DuPont1 is paying for technology to filter - but not eliminate - the toxin from six area water systems.

Next month, the first of approximately 3,500 personal injury lawsuits2 from mid-Ohio Valley residents who got sick from drinking the contaminated water will go to trial. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has spent a decade studying the health hazards of the Teflon chemical, known as PFOA,3 but may take another four to six years before even deciding whether to set a legally enforceable maximum pollution level for drinking water. In 2009, EPA set a non-enforceable Provisional Health Advisory level - a temporary, voluntary standard to help utilities and health officials decide when to take action to reduce peoples' exposure - but the agency didn't follow up with a rule that carries the force of law. That advisory level remains the only federal guidance on how much PFOA is safe in drinking water.

Now two leading environmental health scientists have published research with alarming implications: PFOA contamination of drinking water is a much more serious threat to health, both in the mid-Ohio Valley and nationwide, than previously thought. Their research finds that even very tiny concentrations of PFOA - below the reporting limit required by EPA's tests of public water supplies - are harmful. This means that EPA's health advisory level is hundreds or thousands of times too weak to fully protect human health with an adequate margin of safety. The implications:

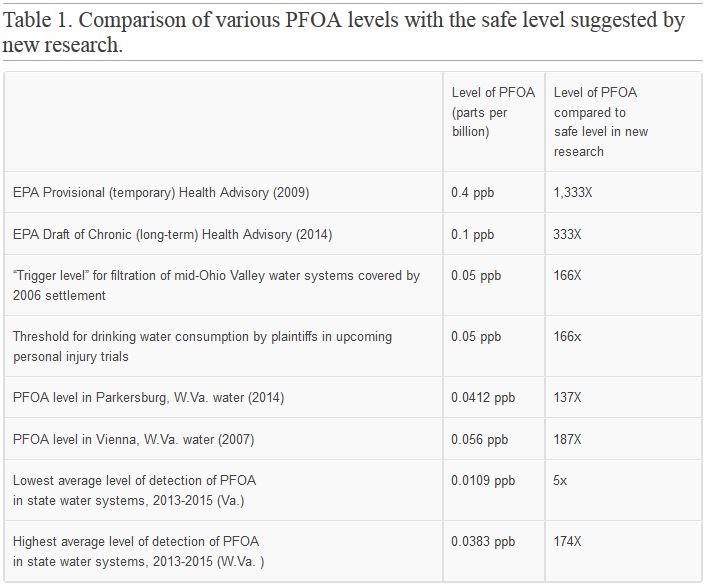

- The settlement set a "trigger level" of PFOA to determine which West Virginia and Ohio water systems DuPont would pay to have filtered. That trigger level is more than 160 times the amount the new research says is safe. Filtration has cut PFOA to almost non-detectable levels in many of the water systems covered by the settlement, but even the least contamination measured exceeds the amount the new research says is safe.

- Only those people in the mid-Ohio Valley who became sick after drinking water at or above that trigger level are eligible to be plaintiffs in the upcoming trials, but the new science indicates that many more people who drank less heavily contaminated water could also have been harmed. (They may file suits in the future, but will not have the benefit of the extraordinary concession DuPont has made for the upcoming trials - that PFOA at the trigger level can cause certain diseases.)

- Two water systems in the region - Parkersburg and Vienna, W. Va. - were not covered by the 2005 settlement because their PFOA contamination at that time was just under the trigger level. Without benefit of the state-of-the art filtration technology installed in other systems, water samples taken in Vienna in May 2007 had PFOA levels more than 180 times higher than the new research says is safe,4 and those taken in Parkersburg last September were more than 130 times the new safe level.

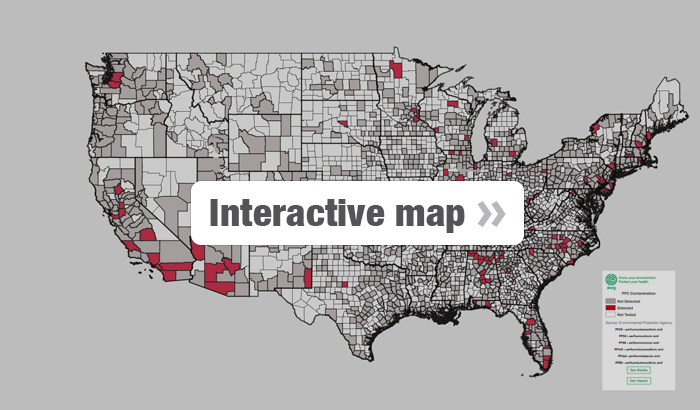

- Since 2013, an EPA testing program has found PFOA in 94 public water systems in 27 states. These systems provide drinking water to more than 6.5 million people. The vast majority of water samples tested had no detectable level of PFOA, and in every system with PFOA the level was well below the EPA advisory level. But among the samples with PFOA, statewide average levels ranged between five times and 175 times the level described by the new research as safe5.

- To replace the provisional health advisory limit set in 2009, EPA officials are in the process of establishing a long-term health advisory level for PFOA in drinking water. A draft EPA study released last year suggested that the advisory level being considered could be more than 300 times the new safe limit. Whatever the new advisory level turns out to be, it will remain voluntary: agency officials have said they could take until 2021 to decide whether to attempt to set a legally enforceable maximum for PFOA.6

Sources: EWG, from Grandjean and Clapp 2015; EPA 2009, 2015; Bilott to EPA 2015.

1 In July 2015 DuPont spun off its fluorochemicals business to a new company named Chemours, which will also inherit DuPont's liabilities for PFOA pollution.

2 The thousands of individual suits have been consolidated into one case in federal district court in Columbus, Ohio. Two individual test cases will be tried first, starting Sept. 14.

3 Perfluorooctanoic acid. DuPont referred to the compound as C8, and much of the regulatory and scientific literature on the pollution in the mid-Ohio Valley uses that designation.

4 Letter from attorney Robert A. Bilott to EPA regional administrators and the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, January 20, 2015.

5 U.S. EPA, Unregulated Contaminants Monitoring Rule 3 (2013-2015) Occurrence Data. June 2015. Available: water.epa.gov/lawsregs/rulesregs/sdwa/ucmr/data.cfm

6 Suzanne Yohannan, EPA Proposes First-Time Risk Values for Chronic PFC Exposures. InsideEPA.com, February 28, 2014. Available: insideepa.com/daily-news/epa-proposes-first-time-risk-values-chronic-pfc-exposures.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter