© RIA Novosti / Yakov Andreev

Humans have long used the behavior of rats to personify the worst qualities in their fellow man. When it comes to acts of kindness, however, it turns out

the much maligned creature is willing to repay favors to its fellow rodents.

The study, published this week in the journal

Biology Letters, was set up to observe an ever elusive concept in the animal kingdom - the principle of direct reciprocity.

According to Michael Taborsky, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland who helped carry out the experiment,

the practice is in fact so rare that this is the first time it has ever been scientifically observed in non-humans.

Along with his Swiss colleague Vassilissa Dolivo, the team brought together 20 female wild-type Norwegian rats. During the experiment, the team used pieces of banana as attractive awards, and pieces of carrots as less attractive rewards.

© royalsocietypublishing.org

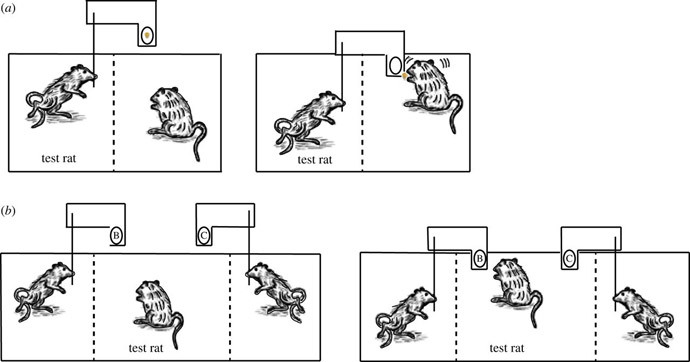

The rats were able to deliver one of these morsels to another rat in an enclosure by pulling a stick. After some time, the rat on the receiving end would begin to differentiate between the quality of its helper based on the type of food it received.

The rats then switched places, with the once-confined rodents pulling sticks to deliver cereal flakes to their previous helpers.

The results:

the rats which had doled out bananas got cereal more quickly and more often than those which had given out carrots.

When asked if the rats were really returning the favor, Taborsky told

National Geographic that it seemed likely, given how they had made the simple association between reward and repayment.

"Two elements are involved: recognizing an individual, and responding to the quality of service," Taborsky said.

Pointing to previous research which demonstrates the ability of rats to recognize each other and their ability to differentiate between better spots to chow down, the idea that the rodents reward each other in order to guarantee such mutually beneficial exchanges in the future "might not be as complex as we think," he added.

I was in the hospital for a couple of weeks. I would collect leftover bread from the meals and go outside to feed the crows. The day before I checked out, there were sea shells, unique sticks, feathers and similar objects neatly arranged in the 2 places I fed the crows.