© www.weedist.comWhy do common folk have to educate law enforcement?

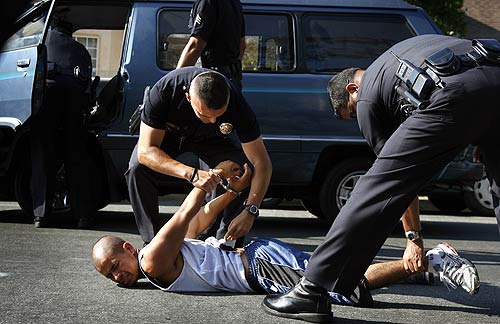

It was 11 years ago when we first argued that constitutional protections can be balanced against national security interests, and that racial profiling is bad policing practice because it's ineffective and hurts law enforcement's legitimacy in communities. Sadly, racial profiling is used in 2014 as much as it was in 2003, and too often with deadly consequences. The deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner reminded those who don't experience racial profiling that many police in America

still regularly treat African Americans differently than white people.So while we - and others - applaud US attorney general Eric Holder's plan to update the federal government's racial profiling guideline, the new rules announced this week

won't do nearly enough to end pervasive, race-based policing practices.

The biggest problem is that the federal profiling guidelines don't address the profiling actions of local law enforcement:

they only apply to federal law enforcement agencies and local officials working with them on

federal projects. The new guidelines are merely supposed to inspire local police to design their own - but local police departments pride themselves on their autonomy and aren't interested in the federal government telling them how to operate.

© www.collective-evolution.com"We're going to go out there and violate some rights." -NYPD Officer

There are only two situations in which police departments (reluctantly) accept federal directives about their policies should be done. One is when the US Department of Justice finds that local police engaged in a

pattern of constitutional violation - which it did recently, finding that the Cleveland Police Department was excessively using force. The other is when a federal court finds that local police engaged in

unconstitutional policing practices - as a court did last year, finding that the New York City Police Department's stops-and-frisk program was unconstitutional because it targeted minorities.

Another problem with the guidelines is that they broadly

exempt many activities of the federal law enforcement agencies in the name of homeland security that one would expect to have to abide by the rules:

US Border Patrol agents, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, Transportation Security Administration agents and the US Secret Service are all exempt. Such broad exceptions to the rules certainly don't help make the guidelines seem more legitimate in the eyes of ethnic minority populations and heighten the public scepticism of the government's commitment to curbing profiling .

A growing body of science tells us that police, like the general public, associate African Americans with crime and violence: studies, including ones by 2014 MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant winner Jennifer Eberhardt and researcher Joshua Correll, show that police officers still often

associate black faces with criminality. But science also shows that

racial bias is often unconscious, not overt race-based decision making - and making decisions based on stereotypes one isn't conscious of is difficult to change.

But people, and law enforcement agents, can change.

Police officers who get better training to counteract implicit racial bias can potentially see its effects reduced in their day-to-day decision-making. Increasing racial diversity throughout the ranks of local police departments - from police chiefs to patrol officers - also engenders in minority communities more trust and confidence in police, and helps reduce officer bias.

President Obama's recently-established

Task Force on 21st Century Policing is an important opportunity to make long-needed changes to police departments that still use explicit or implicit racial profiling, and it shouldn't be squandered. The Task Force should recommend the creation of, and carve out a budget for, a national police training centre for local police that would host mandatory training for local police officers focused on ending racial profiling and repairing eroded police legitimacy.

The curriculum, developed with law enforcement, community and academic stakeholders, would focus on

procedural justice training and how to deliver services to community members. By providing police with skills in listening, communication and transparency, procedural justice trainings developed by Tom Tyler and colleagues have been successful in improving trust and confidence in the police in pilot cities including New Orleans and Manchester in the UK.

Police must work with communities to improve their relationships, not operate in opposition to the people they are supposed to serve:

communities are not the enemy. If we can make increasing their perceived legitimacy a central focus of every local police department, and help police officers understand how their implicit biases negatively affect their work and their communities, the end of racial profiling will finally be in sight.

Comment: Why do Americans still invest their faith and free will in systems that are obviously to their detriment no matter what their color, race or gender? When police are mandated to quotas in order to keep their jobs or qualify for promotions - it means the police departments are holding their officers hostage, who then look for easy targets. It is no longer law enforcement by the book, it is by the numbers.

Officers are encouraged to disregard rights, instigate fear tactics, break the law, and use brutality to harass innocent victims as part of a "hush policy" endorsed by law enforcement hierarchy, ever-widening the gap and blurring the lines between those they are obligated "to protect" and the pathocracy they serve. When did the the people make law enforcement their unrestrained overlords and prison masters? Did they not notice the insidious encroachment of a totalitarian regime?

Procedural justice and racial bias training sounds like a nice remedy. It is a fix that can't. The racial protocol is now systemic in departments all over the country, observable by the skyrocketing increase in racial profiling, innocent deaths caused by police officers, and daily abuse without provocation. And, understandably, the reaction of the common people is mounting. But, how do you put the cat back in the bag once it has usurped power it was never meant to have? When it becomes "us versus them" we have lost an important fundamental basis in the ability to function as a united and healthy society. These abuses of power that lead to the deaths of innocent persons must end and those who perpetrate these atrocities must be held accountable in a court of REAL law and justice. If not, we are all victims of a system in which we have good reason to no longer trust or believe.