When Josephine Wilson, 37, of Princeton, New Jersey, took her 1-year-old daughter to the pediatrician for a routine visit in July 2013, a flyer for a study on flame retardants in mothers and children caught her eye. The substances, found in furniture, electronics, and appliances, were on her radar because she'd read about potentially dangerous environmental chemicals when she learned she was pregnant. To limit their daughter's exposure, she and her husband had replaced their old sofa with a $3,000 version that uses wool as fire protection - a choice that was "pricey, but well worth it in our minds," she says. When she got home from the pediatrician, she sent urine samples from her and her daughter to the researchers.

Of the 48 participants in the study, which was conducted by the Environmental Working Group and Duke University, the Wilsons' levels were at the low end. Even so, the results weren't exactly comforting. They both tested positive for chlorinated Tris, a flame retardant that was voluntarily removed from use in children's pajamas in the '70s due to cancer concerns but is still used in furniture, as well as an ingredient in Firemaster 550, a newer chemical cocktail that may disrupt hormone signaling. Worse, the level of one chemical was three times higher for Wilson's daughter than it was for her. "We'd done everything we could to remove these chemicals from our immediate environment, and they were still in our bodies," she says. "I'm not sure you can completely avoid them."

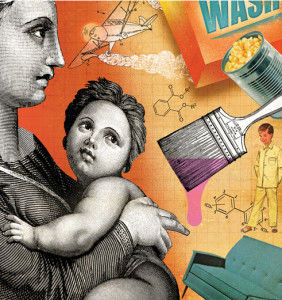

Avoid them? Probably not. Synthetic chemicals are everywhere - some 82,000 at last count, most of which have never been safety-tested. That's because the Environmental Protection Agency's Toxic Substances Control Act, designed to regulate chemicals, is a "broken, toothless piece of legislation," according to Philip Landrigan, M.D., pediatrician and dean for global health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

They're so ubiquitous that we all have at least traces of them in our bodies. In addition to dozens of other worrisome substances, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found the hormone-disrupting chemicals bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates in 93 percent and 73 percent, respectively, of routine blood and urine tests. Studies looking at infants' cord blood have turned up hundreds of man-made toxins - fire retardants, PCBs (banned in 1979), polyaromatic hydrocarbons from burning gasoline, and pesticides. The scariest part? "For 80 percent of chemicals in commercial use today, we have no information on the potential toxicity to babies in the womb or to infants and small children," says Dr. Landrigan. "We're flying without radar."

Comment: More information on the negative health effects of BPA:

What is clear: As environmental exposures have risen, so have the rates of autism, ADHD, child- hood cancer, depression, anxiety, early puberty, and obesity. In 2014, Dr. Landrigan and Phillippe Grandjean, M.D., an adjunct professor of environmental health at the Harvard School of Public Health, published a paper in the journal The Lancet calling the effects on children's cognitive development a "silent pandemic of neurodevelopmental toxicity." Scientists don't throw around the word "pandemic" lightly. They do it to get our attention. And they want to get our attention not just because chemicals are everywhere but because babies and young children - whose cells are rapidly dividing, whose brains and organs are still developing, whose hormones are changing - are uniquely, worryingly vulnerable to their pernicious effects.

The surge in childhood disorders

Finding environmental causes of childhood problems is like trying to pick out a criminal from a lineup of 100 look-alikes. There are many suspects, and proving that a certain substance is responsible requires not only ruling out alternatives but also gathering convincing evidence against the right culprit. So scientists have come to rely on prospective studies, in which they follow mothers during pregnancy, tracking which exposures occur, then keeping tabs on children three, five, or 10 years into childhood to see how they fare. Even those studies reveal only correlations, not causes. But they do raise strong concerns.

Take autism, which afflicts one in 68 children, an increase of 290 percent since 2002. In June, researchers at the Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (MIND) Institute at the University of California, Davis, reported that pregnant women who lived near fields and farms treated with certain chemical pesticides had a 67 percent increased risk of having a child with autism spectrum disorder or another developmental delay.

"During pregnancy, the brain is developing synapses - the spaces between neurons where electrical impulses signal chemical messengers to pass information from neuron to neuron - and that may be where pesticides are disrupting development," says Irva Hertz-Picciotto, Ph.D., a MIND researcher and vice chair of the Department of Public Health Sciences at UC-Davis.

Autism is just one of many developmental disabilities, from dyslexia to cerebral palsy, on the rise. To take another example, the prevalence of ADHD has climbed 33 percent in the last 12 years. Studies have cast suspicion on several chemicals, including lead; phthalates, which are found in plastics and products like nail polish and hair spray; and BPA, which has been banned from baby bottles and sippy cups but is still used in the lining of canned foods and on cash register and ATM receipts.

"Genetic factors account for no more than 30 to 40 percent of all neurodevelopmental disorders, which means that environmental exposures are playing a causal role as well," says Dr. Landrigan. "There's no way that genetic changes, which take centuries to evolve, could be behind the rapid increases in the frequency of these conditions."

The same goes for certain childhood cancers, especially leukemia, says Mark Miller, M.D., M.P.H., director of the University of California, San Francisco, Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit. "Since 1975, the rate of leukemia has increased 55 percent - and the most common type, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, has risen 85 percent," he says. "That jump can't be explained by genes." The search for possible causes has pointed to three main pollutants: tobacco smoke, paint and petroleum solvents (including those found in traffic pollution), and pesticides. "There's evidence that both pre- and post-natal exposure might be a problem," says Dr. Miller. "And in some cases leukemia might be triggered by two hits - one prenatally and another exposure later that ultimately pushes white blood cells to become abnormal."

Scientists suspect a similar phenomenon may be at work when kids are exposed to two or more chemicals that have compa rable effects on the body. For instance, several substances in commercial use today are classified as endocrine disruptors, which affect hormones in a variety of ways, from increasing or decreasing their production to imitat ing their effects - and they may be fueling the mysterious uptick in several health conditions, including childhood anxiety and depression and early puberty among girls.

A generation ago, fewer than 5 percent of girls started puberty before age 8; today, that percentage has more than doubled, according to Louise Greenspan, M.D., a pediatric endocrinologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and co-author of The New Puberty: How to Navigate Early Development in Today's Girls. Potential culprits include flame retardants, phthalates, triclosan, BPA, pesticides, detergents, heavy metals like lead and cadmium, and even lavender and tea tree oil, which are potent endocrine disruptors, according to Julianna Deardorff, Ph.D., clinical psychologist and associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley's School of Public Health, who co-authored the book with Dr. Greenspan.

One reason puberty may be inching ever earlier: Childhood obesity is on the rise. In 1980, about 7 percent of kids were obese; by 2012, the number had climbed to 18 percent. Add in kids who are overweight, and more than a third of children under 12 now weigh more than they should. Even that troubling trend has been linked to environmental chemicals. "The more fat kids have, the more estrogen they produce and the more chemicals they store, so overweight kids are exposed to higher levels of potentially dangerous substances," says Dr. Greenspan. "It's a vicious cycle."

All this is enough to make you want to clothe your kids in hazmat overalls. But Dr. Landrigan emphasizes that parents do have power:

"You need to remember that there are things you can do to limit exposure and that healthy factors can counterbalance the harm of chemicals - most important, a loving, supportive family environment and a nutritious diet."He and other experts say taking these steps can make a difference:

Eat Organic. The majority of kids' pesticide exposure comes through food. When researchers at Harvard University and the University of Washing- ton substituted organic food for children's typical diets for five days, they found the metabolites for organophosphate pesticides disappeared from their urine and remained undetectable until they started eating their usual diets again. The next best thing to going organic: choosing fruits and vegetables with lower pesticide residues (find a list of the "Dirty Dozen" and "Clean 15" here) and scrub them with water to further reduce surface chemicals.Why are children so vulnerable

Drink filtered water. Read your water district's Consumer Confidence Report to see the types and levels of contaminants in your drinking water, recommends Johanna Congleton, Ph.D., a senior scientist with the Environmental Working Group. "If you're concerned about what you see, there are lots of filter options that range in efficacy and price."

Pass up foods that come from antibiotic treated animals. "Antibiotics appear to act like hormone-disrupting chemicals," says Deardorff.

Cut back on canned foods. Unless the can is labeled BPA-free, it's most likely lined with BPA-containing resin.

Avoid using plastic containers. Some research has shown that BPA can seep into food or beverages from containers that contain the chemical, especially when heated.

Vacuum and dust with a damp rag or sponge every two or three days. "Household dust is a major vehicle for kids' chemical exposures," says Julie Herbstman, Ph.D., assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health.

Avoid burning candles and fires. "Things you burn may contain potentially harmful chemicals," says Herbstman, who also advises buying a HEPA filter, which may cut down on indoor air pollution.

Use natural pest killing products. "Conventional ones contain dangerous chemicals that you don't want kids exposed to," says Dr. Landrigan.

Trying to get pregnant, take folic acid. "We found that women who took the supplement three months before pregnancy or in the first month after conception were at reduced risk of having a child with autism - and we're now examining whether it reduces the impact of in vitro pesticide exposure on autism risk," says Hertz-Picciotto of the UC-Davis MIND Institute. More good news: Researchers from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium recently reported that the kids of women who took folic acid before or during pregnancy were less likely to get leukemia.

Pound for pound, kids are at increased risk from chemical exposures because their systems are still developing. Tissues with rapidly dividing cells, like the blood and lungs, are especially vulnerable to carcinogens in the first nine months after birth, when cell division is most accelerated, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. "Every time a cell divides there's an opportunity for mutations to occur," says Julie Herbstman, Ph.D., assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. Other reasons kids are at greater risk:

Their size. Children breathe more air, drink more water, and eat more food per pound of body weight than adults do.How you can take action

Their skin. The ratio of babies' skin surface to their body weight is about three times greater than that of an adult, which means that even a seemingly small dollop of lotion or sunscreen applied to their skin is a fairly large "dose." Babies' skin also more readily absorbs chemicals during the first two months, before the thick keratin layer that protects adult skin from toxins starts to form.

Their breathing. Newborns take an average of about 45 breaths per minute, which makes their developing respiratory systems more vulnerable to airborne pollutants. Two- year-olds take between 24 and 40, and teens settle into an adult rate of about 12 to 14 breaths per minute.

Their Metabolism. Newborns have far lower levels of the enzyme PON1, which affects the body's ability to detoxify and eliminate chemicals. Later, during adolescence, chromosomal changes decrease the rate at which kids metabolize chemical substances. Also, during puberty, there's rapid growth, division, and differentiation among thousands of cells that can make kids especially sensitive to chemicals that mimic hormones.

Their diet. The average child drinks far more apple juice and grape juice and eats more grapes, bananas, carrots, and other fruits and vegetables than adults, so their exposure to chemicals that could be on produce is greater.

Their playing field. Children crawl and play on carpets containing dust that may harbor chemicals and on grass that might have been sprayed with pesticides.

Their Behavior. Kids are curious, and they often explore their environments by putting things in their mouths.

In 1976, when Congress passed the Toxic Substances Control Act, there were 62,000 substances in use in the U.S. - all of which were presumed to be safe, without scrutiny or testing of any kind. Since then, another 20,000 chemicals have come on the market, and few of those have been tested. "It's not like the FDA, which requires that drug companies test their products before they get approval," says Philip Landrigan, M.D. "With consumer chemicals, we start using them and see if problems arise." But various legislators and organizations, including the Environmental Working Group, the Environmental Defense Fund, and Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families, are trying to change that. One way to get involved: Join the EWG's email campaign to members of Congress. Find out how you can take action here.

Comment: For more information about toxins in the body and their negative effects on human health read Detoxify or Die By Sherry A. Rogers, M.D.: