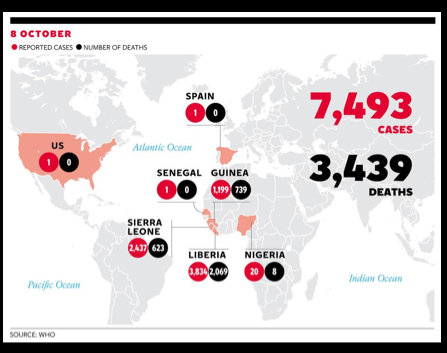

Ebola, the virus that has ravaged Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea at an unprecedented rate, continues its devastating spread. The number of dead doubles with each passing month; the bodies unburied. More lives are devastated with each passing day.

And in the absence of a mass-produced vaccine, its treatment - enforced isolation, mass quarantines - now threatens to bring a new crisis: starvation.

Earlier this month, two children who were among the thousands orphaned by the virus, were visited by aid workers in Liberia's capital, Monrovia. At the time, the workers did not have the resources to take the children away. When they returned days later, the children were dead. They died not from Ebola, but starvation.

Yesterday, as the World Health Organisation warned that more than 4,500 people would be dead before the end of the week, a new threat to West Africa's stability emerged: three quarters of a million people may die from malnutrition, as an unprecedented modern famine follows the disease - if urgent action is not taken. While Ebola's direct consequences prompt terror, its indirect results are equally disturbing - food prices spiral, farms are abandoned, meals are scarce and those most in need, the estimated 4,000 orphans of the virus, go hungry.

Speaking on the eve of World Food Day, Denise Brown, the United Nations World Food Programme's regional director for West Africa, said: "The world is mobilising and we need to reach the smallest villages in the most remote locations.

"Indications are that things will get worse before they improve. How much worse depends on us all."

The UN agency estimates that it has provided food to a little over half a million people in the three worst-hit countries. It is aiming to feed at least another 600,000 before the end of October.

But for Tom Dannatt, founder and chief executive of Street Child, a specialist West Africa children's charity, the food crisis in West Africa is not unexpected.

If current projections are correct, there could be up to 10,000 Ebola cases a week in West Africa before Christmas. That would, if mortality projections of 70 per cent remain correct, result in 7,000 deaths every week and thousands more orphans.

Speaking to The Independent yesterday, Mr Dannatt described the "very patchy" feeding programmes in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

"Some get food, others don't," he said. "They go unfed and they don't have the right nutrients and they are then susceptible to disease. They break the quarantine and go out in town to eat [so] the infection spreads."

Some districts in Sierra Leone have been under quarantine for 10 weeks.

"Life in those districts - it's like holding your breath: you can do it for a while, but you can't do it for huge periods," said Mr Dannatt. "It's the most vulnerable that reach the sharp end first."

Yesterday, Koinadugu in the country's far north - the last district where Ebola had not previously reached - recorded its first two cases.

Mr Dannatt said food prices in quarantined districts had increased by up to 100 per cent for certain goods, while opportunities to earn money were greatly reduced.

"Villagers and agricultural workers are frightened to go out to the field to do their normal work. They are frightened to go market as well," he said.

On Monday, Kanayo Nwanze, president of the UN International Fund for Agricultural Development, said that up to 40 per cent of farms have been abandoned in the worst-affected areas of Sierra Leone. There are already food shortages in Senegal and other countries in West Africa, because regional trade has been disrupted.

According to the World Food Programme's survey of people in the Kailahun and Kenema districts of Sierra Leone - where most Ebola cases have been reported - many are resorting to desperate measures to cope - often making do with scraps.

In Lofa County, the worst affected rural area in Liberia, the price of food and other commodities increased from 30 to 75 per cent, just in August. The NGO Action Against Hunger said the price of cassava - a key staple - increased by almost 150 per cent in the Liberian capital, Monrovia, during the first week in August.

It is not just food that is scarce in Liberia. The country and its overwhelmed government also faces a projected shortage of 80,000 body bags to bury the dead and 100,000kg of chlorine powder to disinfect quarantine zones.

"This has been coming as obviously and clearly as light at the end of the night." He added: "The excuse is, 'We're focused on just stopping Ebola'. I find it frustrating when people say the hungry will get through it. I wonder whether that division is an accurate one. If we made sure every quarantined family was fed a proper ration they wouldn't break out and infect others."

An Oxfam spokesperson said yesterday: "The priority for Oxfam and other aid agencies at this stage is to bring the Ebola outbreak under control by scaling up our response.

"Nevertheless, the wider impact of this crisis is already tangible. People are losing their income as fields, markets and goods are inaccessible, and [are] thus being pushed further into poverty.

"There is less local food in markets and what is there is becoming more expensive. In some areas, this already means that people do not have enough food to eat. This crisis has wiped away years of development gains, hard-won after brutal civil wars, which is likely to increase the fragility of the countries and stability of the region."

Mr Dannatt added: "The saving Grace of West Africa in terms of Ebola may be in this miniscule, overblown link to the West; that it might come and get you - it's bewildering and extraordinary."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter