* The team found that 50 per cent of such stars were in binary systems

* This means more planets than thought are orbiting multiple stars

* Some of the planets may never-ending day time, while others would just have an unusually bright second star among others in their night sky

Imagine a world where it's never night time; when one sun moves below the horizon another takes its place, providing endless light.

This might sound like a sci-fi scenario, but research now suggests that this could be far more common than thought.

In fact, up to 50 per cent of stars hosting planets may actually be in binary systems, providing their worlds with odd characteristics not seen in our solar system.

The research was carried out by astronomers led by Dr Elliott Horch from Southern Connecticut State University.

It had previously been known that binary stars were commonplace, with half the stars in the night sky orbiting at least one other.

But it had been unknown how such companion stars affected the formation of planets.

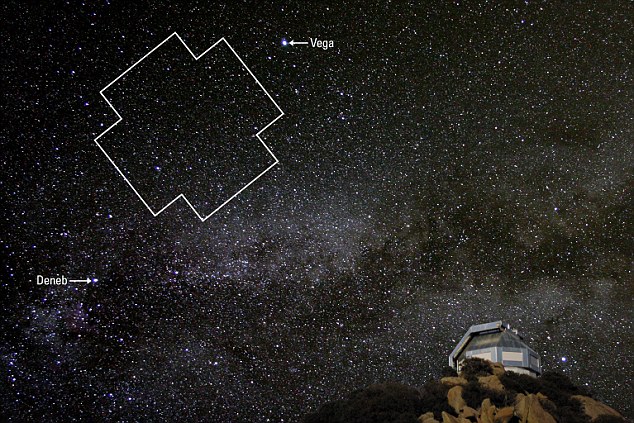

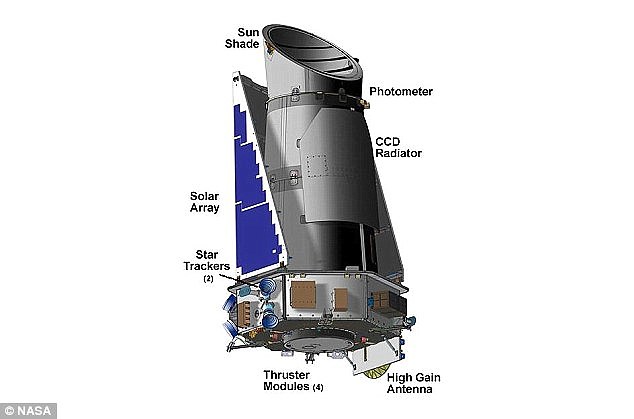

Now it seems that such binary systems have little effect, with half of the planets discovered to date by the Kepler space telescope found to be in orbit around binary stars.

These are known as circumbinary planets, those that orbit two stars.

How these planets come to orbit two stars is unknown, however; it's thought they may be plucked from elsewhere.

The team used the WIYN telescope on Kitt Peak in southern Arizona and the Gemini North Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii to make the discovery.

This equated to stars ranging in distance from 100 times the Earth-sun distance to just a few times this distance.

And in the study they found that about 50 per cent of stars with planets in orbit around them were actually in a binary system.

'It's interesting and exciting that exoplanet systems with stellar companions turn out to be much more common than was believed even just a few years ago,' said Dr Horch.

And another intriguing conclusion of the study is that, for any given circumbinary planet, it is difficult to work out which star it is orbiting.

Co-author of the study, Dr. Steve Howell of Nasa Ames Research Center, said: 'An interesting consequence of this finding is that in the half of the exoplanet host stars that are binary we can not, in general, say which star in the system the planet actually orbits.'

While some planets may resemble Tatooine from Star Wars, with two bright suns in the sky, other circumbinary planets in wide orbits around their stars may simply have one unusually bright star among others in their sky in addition to their sun.

'Somewhere there will be a transition between these two scenarios, but we are far from knowing where,' added Dr Howell.

IAU TO LET PUBLIC NAME PLANETS

To date, nearly all planets found outside the solar system have followed a strict naming convention, which has led to rather complicated names such as the world OGLE235-MOA53 b.

That's all set to change later this year, though, as the International Astronomical Union (IAU) will allow the public to vote on the names of exoplanets for the first time.

A list of 305 confirmed planets found before 31 December 2008 has been drawn up, and in October names can be submitted for consideration for some of the planets.

In March 2015 the public will be allowed to vote on the proposed names and in August 2015 the results will be announced at a ceremony in Honolulu.

The names of planets will coexist alongside their existing scientific names, just like what is done for other celestial bodies now.

For example the Orion Nebula is also scientifically known as Messier 42.

Still we ask about the sun's companion star. But Walt Cruttenden had pretty solid proofs it was Sirius. Where is the mistake ?