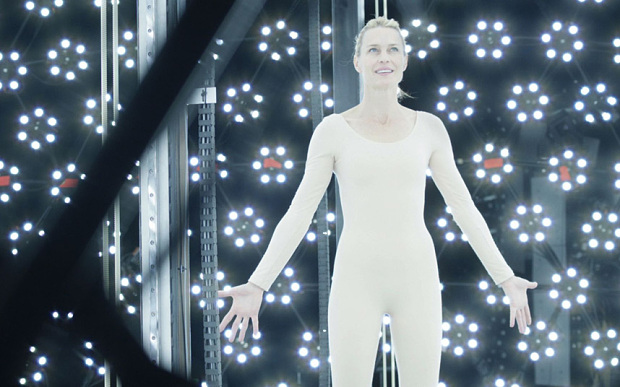

Princess Bride fans needn't panic just yet, though. The scene is from Ari Folman's new film The Congress - a trippy, dystopian vision of a future in which artifice has displaced reality. But it is a future that may be closer than we think.

Virtual characters in films are nothing new. The first - a computer-generated knight - appeared in The Young Sherlock in 1985, and since then we've seen everything from artificial extras in Titanic to detailed motion-capture characters such as Gollum in The Lord of the Rings. And while some virtual human faces still creep us out (Polar Express, anyone?), a few have graced our screens without us even realising. Brad Pitt's reverse-ageing process in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, for example, was created not with prosthetics but with computer-generated imagery (CGI).

"Very few people watching that film even knew that [CGI] was going on," says Darren Hendler, digital effects supervisor at Digital Domain. "We are at the point where we can create a digital version of an actor that is indistinguishable from the real person."

There are plenty of reasons to welcome the technology. Eventually, it could democratise movies, allowing anybody to make a film using a cast they have created. There are also financial advantages, says Professor Nadia Magnenat Thalmann, who has pioneered research into virtual humans for the past 30 years. "On some films it costs a fortune to hire real actors," she says. "We're able to make virtual actors look great - and as soon as we can automate the process, there will be a cost-benefit analysis. If it's cheaper, second-rank actors will be done more and more by computer."

According to Hendler, some actors are already embracing the process and having themselves scanned. "If they're in a movie later on where they need to be younger, they already have that snapshot," he says. "They are starting to archive their digital selves." But they're also wary. Tom Cruise, who was scanned for his role in Oblivion, had his data hand-delivered to his house and all other copies destroyed. "The more experienced actors will start to have more control over their contracts with the studios; more say over how their final digital likeness looks and how it is used," says Hendler.

But if Folman's vision becomes a reality, films might even be cast using digital versions of actors who have long since died. It is already possible to create fairly convincing virtual versions of actors who were never scanned, using old footage and performance doubles. And, a CG version of Paul Walker has been created to complete Fast and Furious 7, after the actor died part-way through filming.

There are also developments that could make real actors, even in their digital forms, completely redundant. "The big trend is to make virtual humans conscious of their environment and intelligent," says Magnenat Thalmann. If successful, film-makers will one day be able to create virtual actors who respond to their direction autonomously.

Luckily for the acting community, this technology is nowhere near fruition. "I think the top actors have nice days in front of them," says Magnenat Thalmann. "Because, although I've pioneered this field of virtual humans, I have never seen one that is realistic that can also act."

Hendler, meanwhile, thinks any virtual character will be useless without a human driving the performance. "More and more we're finding that we have to rely on actors to create anything that's moving and believable," he says. "The motion-capture techniques are getting better all the time and I think we'll always rely on the capture of an actor, because that's what an actor does. We can't just create a performance out of thin air."

For now, it seems, Folman's dystopian fantasy will remain just that.

[Link]