America has a slew of enduring mysteries: Who killed the Black Dahlia? What happened to Judge Crater? Where is Jimmy Hoffa? One of the most baffling is "Who was the Boy in the Box?"

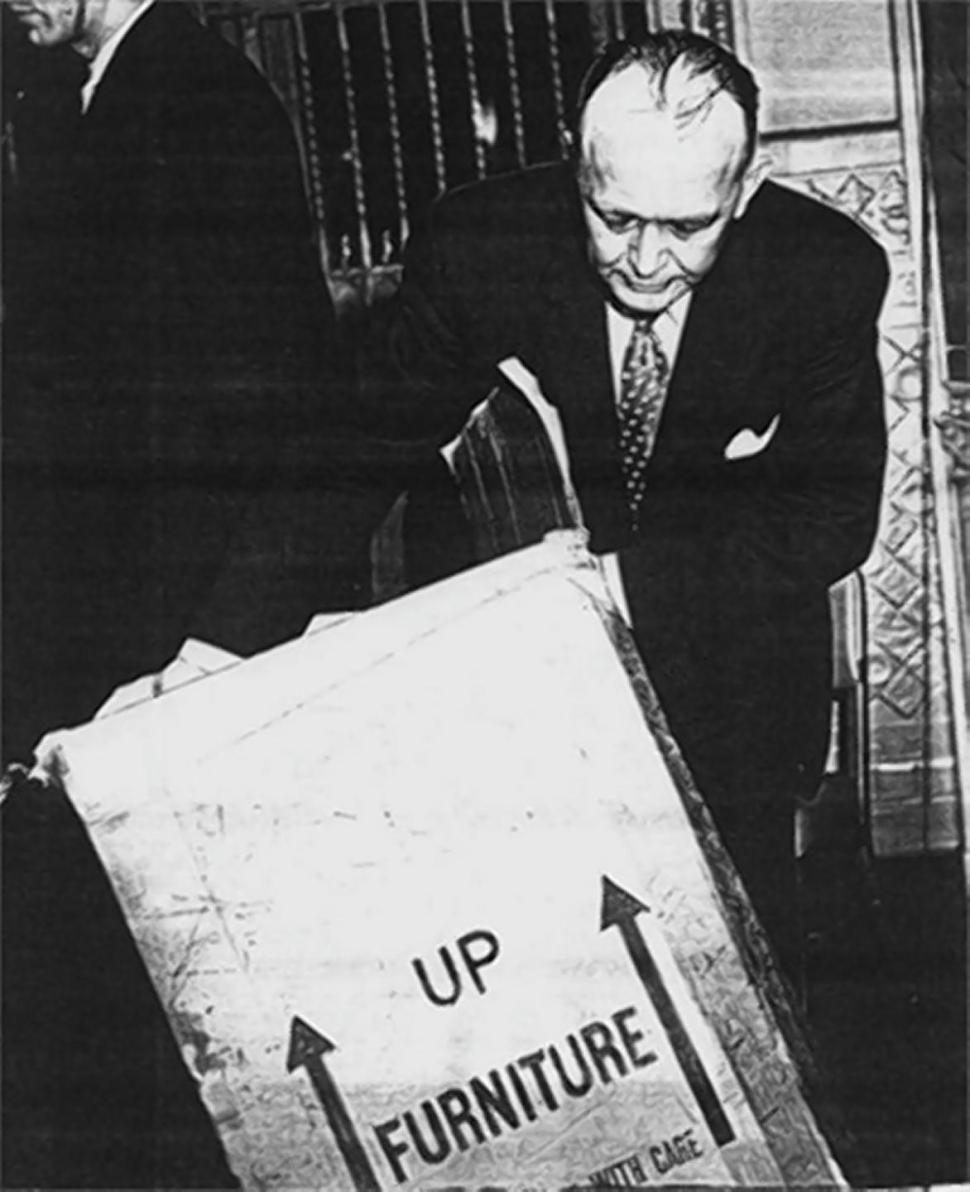

His face became known to the world on the frigid afternoon of Feb. 25, 1957, when a traveler along the Susquehanna Road in Philadelphia noticed a carton with red letters spelling out the words "Furniture, Fragile, Do not Open with Knife." It originally contained a bassinet.

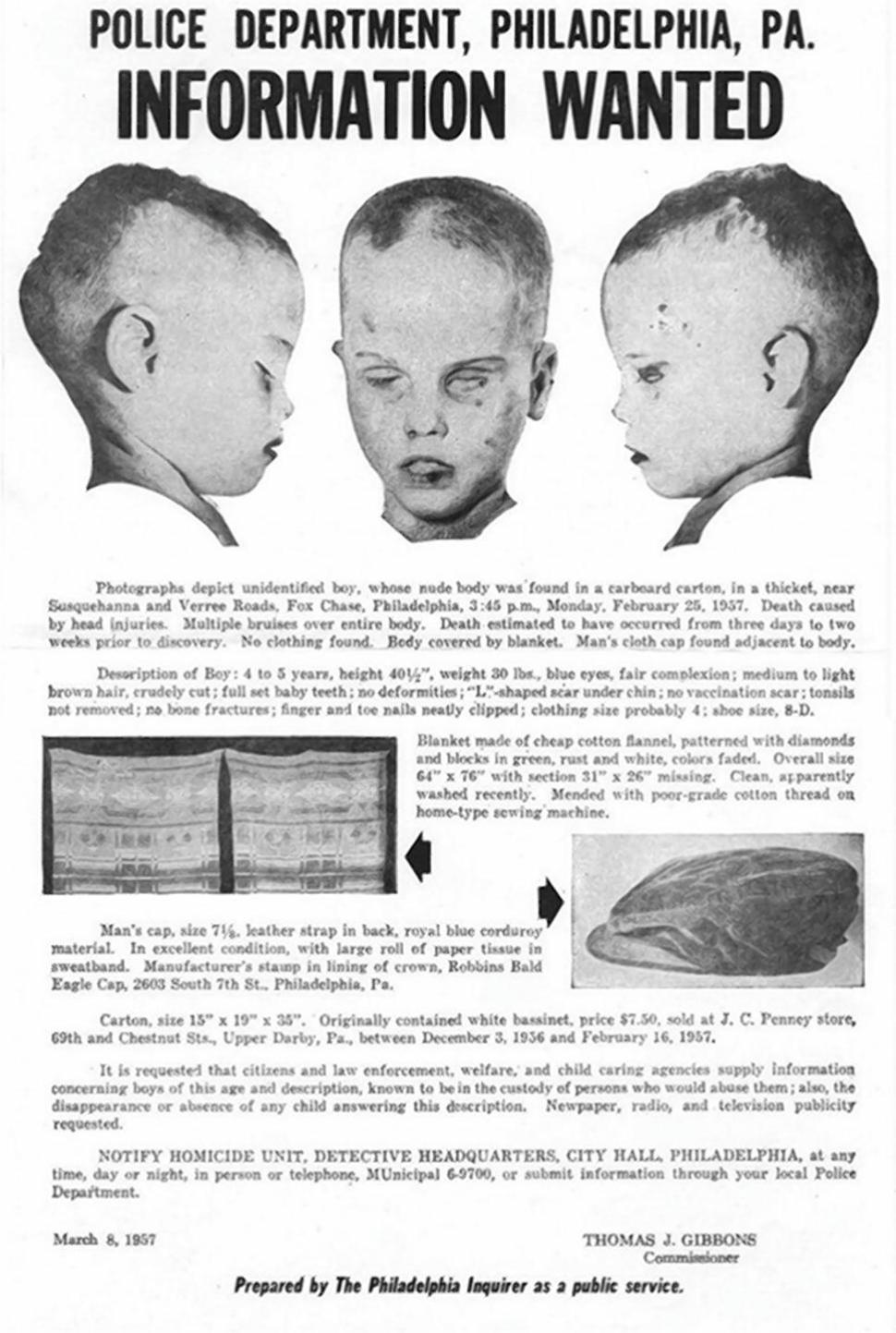

Inside, there was what at first appeared to be a doll, but was really a child's corpse. He was naked and wrapped in a Navaho blanket. At about 40 inches he weighed only 30 pounds, significantly less than what's normal for a child that height.

He could have been anywhere from 3 to 6 years old. His nails had been carefully trimmed and his hair was clipped in a way that suggested it was not the work of a skilled barber. A few of the seven scars on his body seemed to have come from surgical procedures, and his eye showed signs that he had been treated for a chronic condition.

There was a dark substance in the boy's esophagus, but he had not eaten for about three hours before his death. Bruises told of a beating, and the medical examiner ruled that death was caused by blows to the head.

There were plenty of clues to follow. Police first tried to find the identity of the boy, but no children of his size had been reported missing and a scan of orphanages turned up nothing. Hospitals take the foot and fingerprints of newborns, but there were no matches. Hundreds of thousands of posters, flyers and circulars went out to police and were tucked into utility bills, posted in supermarkets, liquor stores and racetracks. Nothing.

In desperation, police dressed the dead boy in the kinds of clothing he might have worn in life - overalls and a shirt - and photographed him sitting up, hoping to jog a memory. Still nothing.

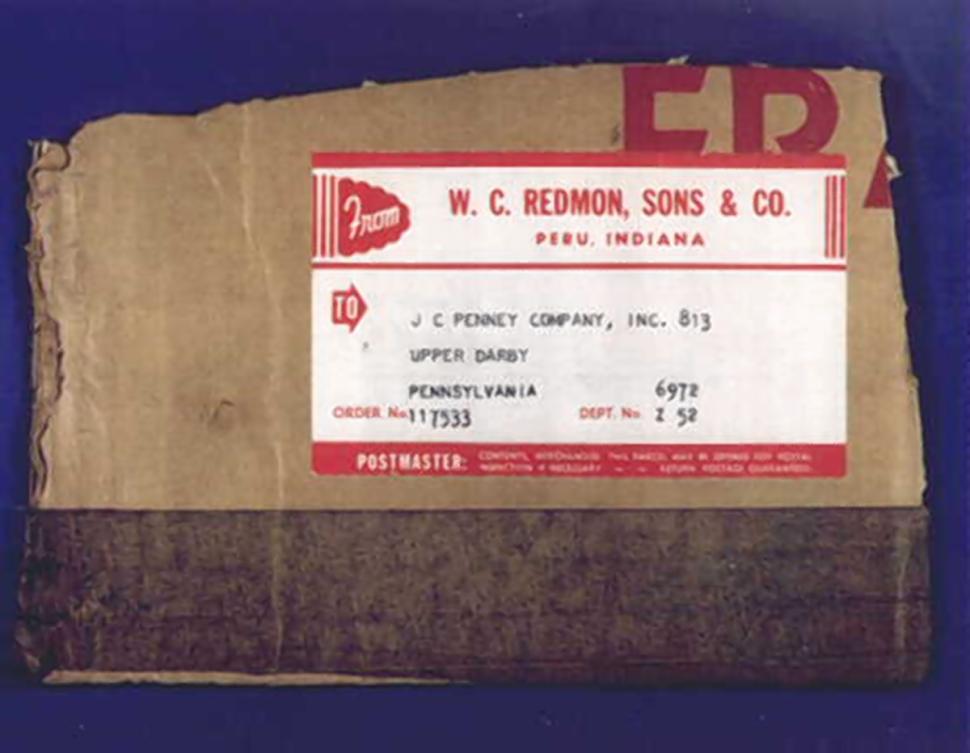

It was easy to trace the box to a local J.C. Penney, but it turned into another dead end. Whoever bought the bassinet paid cash and left, leaving no identification.

Another clue came from a witness, a man who had been driving along the road the day before the body was found. The driver saw a woman and a boy standing beside a car, rummaging through the trunk. Figuring they might have car trouble, he slowed and asked if they needed help. The woman waved him on.

Detectives probed families living on the fringes of society, the kinds of people who had more children than they could support, such as traveling carny workers who had lost some children to disease, and a foster home nearby. Rumors had placed a small boy fitting the description in their homes, but police could confirm nothing. A mother of nine in Colorado fell under suspicion because of a previous charge of having dumped her daughter's corpse in a trash can after the child died of natural causes. But there were only rumors behind these leads.

In July 1957, detectives paid for a funeral. The epitaph on the simple stone marker in Potter's Field read: "Heavenly Father, Bless this Unknown Boy, February 25, 1957."

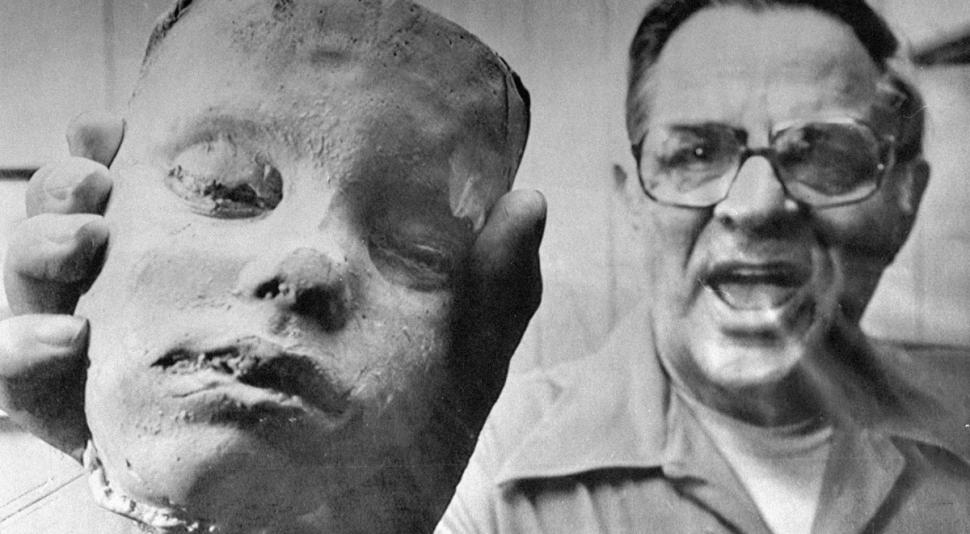

The case cooled and then went cold, except for one investigator from the medical examiner's office - Remington Bristow - who could not let it go.

On his own time and with his own money, he called upon psychics, conducted his own investigations and interviewed anyone who might shed some light on the identity of the boy. Bristow was certain that he had died in a foster home that had taken in many children over the years, but he could prove nothing. He went to his grave in 1993, still wondering.

Five years later, there was a flurry of activity, spurred in part by a group of crimefighting experts known as the Vidocq Society (after legendary French detective Eugène-François Vidocq). The boy's body was exhumed and DNA was taken for testing. Then, the child was given a proper burial in a local cemetery.

Modern forensics proved no more successful than the methods of nearly a half-century earlier. DNA yielded nothing, and even widespread publicity - including a segment on "America's Most Wanted" - brought in a lot of calls, but still no proof.

It all seemed to make sense; she knew key details. The autopsy report, for example, noted that the boy had some brown substance in his esophagus. She said that he had thrown up baked beans the day he died. But there was no way to prove if anything she said was true.

Today, there is a website dedicated to the mystery, and investigators still hope that it may someday be solved. In November 2013, the Vidocq Society held a memorial for the boy who had no name, but nevertheless managed to leave an indelible mark on the world.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter