© Ronald Grant ArchivePeople associate features such as a furrowed brow with untrustworthiness.

The human brain can judge the apparent trustworthiness of a face from a glimpse so fleeting, the person has no idea they have seen it, scientists claim.

Researchers in the US found that brain activity changed in response to how trustworthy a face appeared to be when the face in question had not been consciously perceived.

Scientists made the surprise discovery during a series of experiments that were designed to shed light on the the neural processes that underpin the snap judgments people make about others.

The findings suggest that parts of our brains are doing more complex subconscious processing of the outside world than many researchers thought.

Jonathan Freeman at New York University said the results built on previous work that shows "we form spontaneous judgments of other people that can be largely outside awareness."

The study focused on the activity of the amygdala, a small almond-shaped region deep inside the brain. The amygdala is intimately involved with processing strong emotions, such as fear. Its central nucleus sends out the signals responsible for the famous and evolutionarily crucial "fight-or-flight" response.

Prior to the study, Freeman asked a group of volunteers to rate the trustworthiness of a series of faces. People tend to agree when they rank trustworthiness - faces with several key features, such as more furrowed brows and shallower cheekbones, are consistently rated as less trustworthy.

Freeman then invited a different group of people to take part in the experiments. Each lay in an MRI scanner while images of faces flashed up on a screen before them. Each trustworthy or untrustworthy face flashed up for a matter of milliseconds. Though their eyes had glimpsed the images, the participants were not aware they had seen the faces.

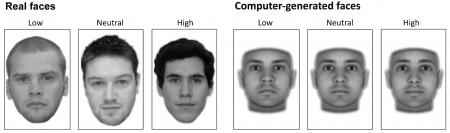

© Journal of NeuroscienceFaces, ranging from low to high trustworthiness.

Even so, the brain scans revealed that the amygdala responded differently to subliminal images of trustworthy and untrustworthy faces. Some regions of the amygdala reacted to how untrustworthy a face was, while other regions seemed to register the overall strength of the judgment, becoming more active only when a face was either very trustworthy or very untrustworthy.

Freeman said the biggest question now was whether the brain activity altered how people behaved. "Even though people might not have conscious awareness, they might move back very subtly when perceiving an untrustworthy face, but that is still unknown," he said. Details of the study appear in the

Journal of Neuroscience.Previous work has shown that the amygdala reacts to scary subliminal images, but to find that the structure made judgment calls on trustworthiness was unexpected.

"The social cues for trustworthiness are considerably more subtle and complex than a simple, fearful expression on a clearly emotional face. It suggests that the amygdala's processing of social cues outside awareness may be more extensive than we thought ," Freeman said.

"The findings are surprising because they show that face evaluation can be done without perceptual awareness," said

Alexander Todorov, professor of psychology at Princeton University. "Even if we are unaware of perceptual information, our brain, in this particular case the amygdala, is capable of processing this information."

Reader Comments

Nice research but... eh... what's the point on researching this? so others may fake trustworthy faces?

Maybe the only importance of the article is the suggestion of how much goes in our minds unconsciously, we seriously lack control.

But still, kinda meh research. I know people with the lest trustworthy faces and they are so nice, and some with the happy baby faces are nasty as hell. Totally subjective, irrelevant research in my opinion.