"Are we to go in or stand aside? Of course everybody longs to stand aside."

Herbert Asquith, diary entry, July 31

The crisis so far:

June 28 Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo

July 5 Germany assured Austria-Hungary of its 'faithful support' if action against Serbia led to conflict with Russia

July 23 Austria-Hungary issued its ultimatum to Serbia

July 26 Austria-Hungary rejected the Serb reply

July 28 Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia

July 29 Bombardment of Belgrade began; Russia mobilised on the Austrian frontier

July 30 Russia ordered general mobilisation

July 31 Austria-Hungary ordered general mobilisation. Germany moved to a 'state of imminent threat of war'

Saturday, August 1, 1914

As dawn broke on Saturday August 1 1914, two critical demands made by Germany were awaiting answers. At 7pm the night before, Germany had requested that France state whether it would remain neutral in a Russian-German war. A reply was demanded within 18 hours - by 1pm on Saturday. And at midnight, Germany had given Russia an ultimatum to demobilise within 12 hours.

9am In Paris, Joseph Joffre, commander-in-chief of the army, urged the French cabinet led by René Viviani (pictured right) to announce general mobilisation. France had a plan for deployment - Plan XVII - in the event of war with Germany; it was designed for swift action before Germany could mobilise its reserves. Now Joffre feared the French were losing valuable time - every 24-hour delay, he thought, meant a potential 20km loss of French territory if Germany attacked.

10am In Berlin, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, the German chancellor, chaired a Bundesrat (federal council) meeting whose approval was needed for mobilisation or a declaration of war.He had worked hard to maintain peace, he told the leaders of the German states - 'But we cannot bear Russia's provocation, if we do not want to abdicate as a Great Power in Europe'.

11am Two hours before Germany's deadline to France expired, Baron von Schoen, the Kaiser's ambassador in Paris, presented himself to Viviani to receive France's reply. He was told that France would act 'in accordance with her interests'. Shortly afterwards, the Russian ambassador, Alexander Izvolsky, arrived with news of Germany's ultimatum to Russia. He was desperate to know from Viviani and President Poincaré what France's intentions were.

He feared that the French parliament would not ratify the military alliance with Russia, the terms of which said that France would respond if Germany attacked Russia. When Viviani returned to the cabinet, the order was given to Adolphe Messimy, the war minister, to mobilise, though he was told to hold on to the document until 3.30pm.

Meanwhile in London, it was the start of a Bank Holiday weekend, and the prime minister, for one, regretted that the crisis kept him in London and away from Venetia Stanley, the 26-year-old friend with whom he appeared besotted:

"I can honestly say I have never had a more bitter disappointment."

Herbert Asquith, letter to Venetia Stanley

The Cabinet was to meet at 11am. Beforehand, Sir Edward Grey, the British foreign secretary, telephoned Prince Lichnowsky, the German ambassador (pictured right). Grey asked him whether Germany could give an assurance that France would not be attacked if it remained neutral in a war between Germany and Russia. Lichnowsky understood him to be offering both British neutrality and a guarantee of French neutrality.

11:15am (London time): Lichnowsky sent a telegram to Berlin with what he took to be the offer from Grey and which he believed Grey was taking to Cabinet. The message was not received until shortly after 5pm.

12pm The German ultimatum to Russia expired without reply.

1pm Asquith's Cabinet had been in no mood for war, but three days before had ordered preliminary mobilisation of the Royal Navy. Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, now argued for full mobilisation. John Morley, president of the Board of Trade, and John Simon, Attorney General, led those opposed, saying Britain should not go to war at all.

Herbert Samuel, President of the Local Government Board, emphasised that their decision depended on whether Germany violated Belgian independence or attacked the northern coast of France. During the meeting, Churchill passed notes to Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, attempting to win him round.

"I hold that in all the circumstances if we allowed Belgian neutrality to be trampled down by Germany without exerting ourselves to aid France we should be in a very melancholy position both in regard to our interests and our honour."

Winston Churchill, letter to Lord Robert Cecil, Unionist MP

1:30pm The Cabinet meeting ended and Grey went to meet Paul Cambon, the French ambassador, who had been waiting anxiously at the Foreign Office. Grey could give him no assurances: 'France must take her own decision at this moment, without reckoning on an assistance we are not now in a position to give.' Cambon left the meeting shaking and told Sir Arthur Nicolson, Permanent Under-Secretary at the FO: 'Ils vont nous lâcher - they are going to desert us.'

3:30pm Grey met Lichnowsky, the German ambassador, who now found the Foreign Secretary simply offering the suggestion that if there was war between Germany and Russia, then Germany and France might agree to stand mobilised but not attack each other. There was no guarantee of neutrality on offer after all. Grey told him that 'it would be very difficult to restrain English feeling on any violation of Belgian neutrality' by either France or Germany.

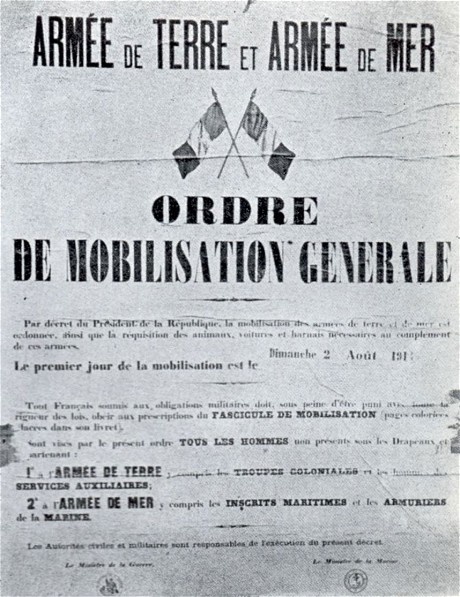

4pm In France, the order for mobilisation was issued, though President Poincaré said it was a precaution and that a peaceful outcome might still be attainable. Posters appeared on the streets of Paris: MOBILISATION GENERALE. LE PREMIER JOUR DE LA MOBILISATION EST LE DIMANCHE 2 AOUT.

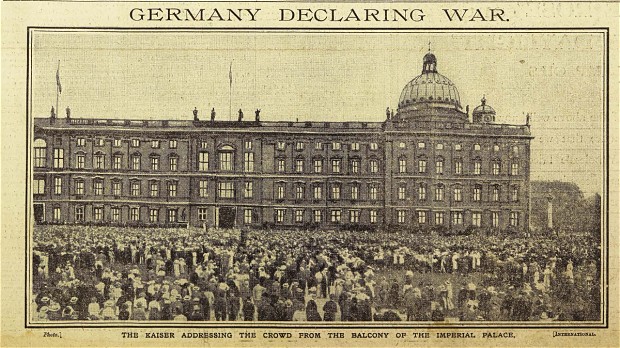

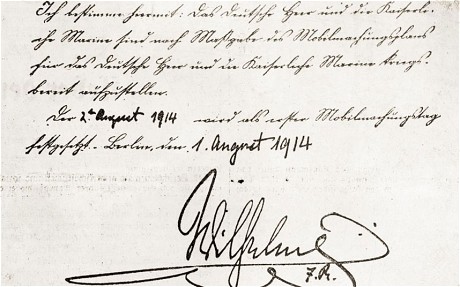

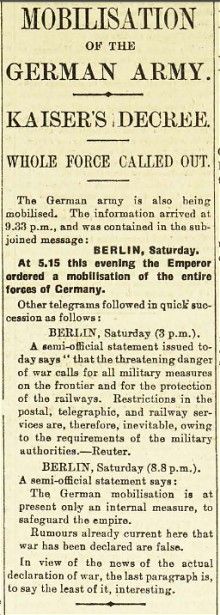

5pm Germany having had no satisfactory response from Russia, the Kaiser signed the decree of general mobilisation. Speaking to an excited crowd from the balcony of his Berlin palace, he said: 'In the battle now lying ahead of us, I see no more parties in my Volk. Among us there are only Germans.'

5:25pm Grey telegrammed Sir Francis Bertie, British ambassador in Paris, with his suggestion that France and Germany might mobilise but actno further. Baffled, Bertie pointed out that France's agreement with the Tsar was unlikely to imply inaction if Germany attacked Russia. 'Am I to enquire precisely what are the obligations of the French under [the] Franco-Russian alliance?' he asked sarcastically.

"For Germany, mobilisation was not a diplomatic tool, it was war itself."

Margaret MacMillan, The War That Ended Peace

"One army corps alone - out of the total of 40 in the German forces - required 170 railway cars for officers, 965 for infantry, 2,960 for cavalry, 1,915 for artillery and supply wagons, 6,010 in all, grouped in 140 trains and an equal number again for their supplies. From the moment the order was given, everything was to move at fixed times according to a schedule precise down to the number of train axles that would pass over a given bridge within a given time."

Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August

7pm The German 16th Division was due to move into Luxembourg as part of Moltke's plan - he knew that Luxembourg's railways were essential for the route through Belgium to France. Bethmann insisted the invasion could not go ahead while the British offer was pending. But the order did not arrive and an infantry company of the 69th Regiment led by a Lt Feldmann made the first frontier crossing of the war and captured the railway station at Ulflingen.

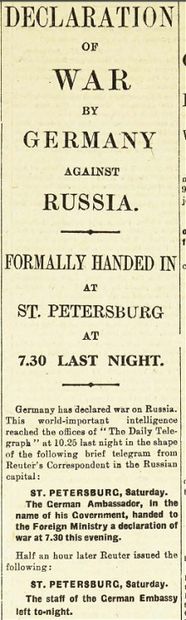

Meanwhile, in St Petersburg, the German ambassador, Count Friedrich Pourtalès, a cousin of Bethmann Hollweg, had handed Germany's declaration of war to Sergei Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister. Pourtalès had been informing Berlin during late July that Russia was bluffing; now he was in tears, and the two men embraced.

7:30pm Paul Eyschen, Prime Minister of Luxembourg, telegraphed London, Paris and Brussels informing them of the incursion, and protested to Berlin.

8pm A further telegram from Lichnowsky in London arrived in Berlin; this explained that Grey had summoned him to their 3.30pm meeting. Meanwhile, the Kaiser had sent a telegram directly to his cousin George V accepting what he believed was the British offer guaranteeing French neutrality. Mobilisation could not be reversed, he said, but 'If France offers me neutrality, which must be guaranteed by the British fleet and army, I shall of course refrain from attacking France and employ my troops elsewhere'. Lichnowsky was authorised to promise that Germany would not cross the French frontier before 7pm on Monday August 3, while discussions went on with Britain.

9pm Grey was summoned to Buckingham Palace to draft the King's reply clearing up the 'misunderstanding' that had come out of his conversation with Lichnowsky that afternoon.

"Sir Edward Grey will arrange to see Prince Lichnowsky early tomorrow to ascertain whether there is a misunderstanding on his part."

George V's telegram to the Kaiser

10:30pm Crowds were pouring on to the streets of St Petersburg. In Paris, the area around the Gare de l'Est was filling with reservists responding to the mobilisation order. In Berlin, the Kaiser - still hoping for peace with Britain - sent a message to his cousin Tsar Nicholas. He said mobilisation had proceeded because Russia had not responded to Germany's request and that Russian troops should not be allowed to cross the frontier.

11pm George V's telegram arrived in Berlin. The Kaiser showed the reply to Moltke, with the words: 'Now you can do what you want'.

In Britain, it was the first day of a bank holiday weekend but holidaymakers were no longer thinking about foreign resorts; the urgent need now was to get home, as the crisis grew. The next morning's Daily Telegraph reported the arrival of the late boat train from Ostend: passengers were telling tales of 'panic' abroad and of their relief at returning to the 'dear old country'.

In those days, all ultimatums were on the table. In the confusion, messages got garbled and the World plunged into a Great War.

In these days, all options are on the table. Ultimatums masquerading as sanctions betray the re-packaging of what is on the table, the War table.

Policy wielders, then as now, wash thier hands in thier own purity. Nothing has changed except the scope of the impending disaster awaiting a puff of wind on the hair trigger.