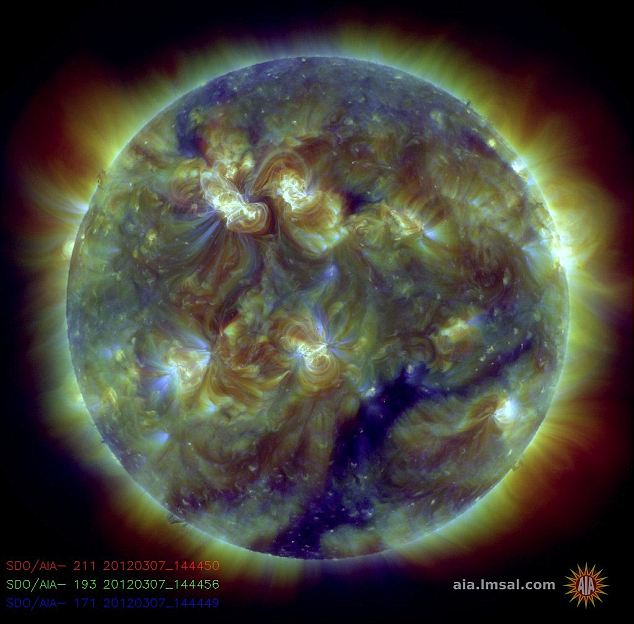

© NASA/AFP/GettyNASA image of a solar storm from 2012

Scientists predict a solar superstorm every 150 years, meaning we are currently five years overdue

Solar "superstorms" pose a catastrophic threat to humanity, scientists have warned.

Solar storms are accompanied by coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, the most energetic events in the solar system, which see huge bubbles of plasma and magnetic fields being spewed from the sun's surface.

A solar superstorm occurs when a CME of sufficient magnitude tears into the Earth's magnetic field and rips it apart. Scientists expect one every 150 years.

Such an event would induce huge surges of electrical currents, causing widespread power failures. The last one was in 1859, before the world depended on electronics.

Ashley Dale, who was a member of SolarMAX, an international task force set up to identify the risks, warned that it was a "matter of time" before such a storm hit again.

The Bristol University researcher, writing in Physics World, said it would wreak havoc with communication systems and power supplies, crippling transport, sanitation and medicine.Scientists have called for a network of satellites to give early warning of such an event.

Mr Dale said: "Without power, people would struggle to fuel their cars at petrol stations, get money from cash dispensers or pay online.

"Water and sewage systems would be affected too, meaning that health epidemics in urbanised areas would quickly take a grip, with diseases we thought we had left behind centuries ago soon returning."

The largest ever solar super-storm on record occurred in 1859 and is known as the Carrington Event, named after the English astronomer Richard Carrington who spotted the preceding solar flare.

This massive CME released about 1022 kJ of energy - the equivalent to 10 billion Hiroshima bombs exploding at the same time - and hurled around a trillion kilos of charged particles towards the Earth at speeds of up to 3000 km/s.

However, its impact on the human population was relatively benign as our electronic infrastructure at the time amounted to no more than about 200,000 kilometres of telegraph lines.

Dale makes it clear in the latest issue of Physics World that these types of events are not just a threat, but inevitable.NASA scientists have predicted that the Earth is in the path of a Carrington-level event every 150 years on average - which means that we are currently five years overdue - and that the likelihood of one occurring in the next decade is as high as 12 per cent.

The 40-strong international team of scientists from SolarMAX gathered at the International Space University in France last year to identify the best ways of limiting the potential damage of a solar super-storm.

A sub-group of scientists concluded that advanced space-weather forecasting is the best solution, which could be achieved by sending an array of 16 lunchbox-sized cube satellites into orbit around the Sun.

The network could give around a week's notice of where, when and with what magnitude solar storms will take place, providing adequate time to switch off vulnerable power lines, re-orientate satellites, ground planes and begin national recovery programmes.

Mr Dale's own solution is to design spacecraft and satellites so that the sensitive, on-board instruments are better protected again sudden increases in radiation from solar storms.

He suggests redistributing the existing internal architecture of a craft so that sensitive payloads are surrounded by non-sensitive bulk material such as polyethylene, aluminium and water.

Mr Dale added: "As a species, we have never been more vulnerable to the volatile mood of our nearest star, but it is well within our ability, skill and expertise as humans to protect ourselves."

Comment: Yet another reason to prepare by setting up one's home with alternative sources of energy, food, first aid, etc.