© unknown

The thing about breaking up is that it's way less fun than falling in love. It's kind of like

jumping into a pile of hot garbage. It's also like trying to kick a cocaine habit.

I should know. About two months ago, the girl that I loved like a maniac was totally driving me crazy (not that I was making her feel particularly sane), so we decided that the year-long rollercoaster of strife-ridden romance we had (mostly) enjoyed had come to its final stop. As twentysomething New York transplants with poor relationship models do, we broke up.

The resulting withdrawal? In a word: awful.

Lucy Brown, a neuroscientist at Yeshiva University, explained to me why. From her 20 years of researching brains in and out of love, she says that when you "hunger" for somebody, it's less of a metaphor than you might think.

"The system that makes you attach to somebody else is at the very same level of thirst and hunger systems," she says.

That level is in what you might call the 'old' or 'reptilian' parts of the brain, operating at an unconscious level. When you get really thirsty, it's this part of the brain that blocks out anything non-hydration related so that you finally get a drink of water. And when you do get a drink of water, it tastes

so good.

A drug of abuse, she says, hops onto that same reward system. And it's the same thing when you meet somebody. "When we fall in love with someone and just want to be with them," Brown explains, "it's at that same level of thirst."

But you don't exactly see it.

"The parts of the brain that deal with cognitive things, like perception, those are more individual and depend on your personality," she says, "but the basic drive toward another individual, another person, the drive for emotional union, the drive to be with them, is at this unconscious level."

Which is part of the reason that breakups are so insanely painful. Research shows that the discomfort people experience when looking at a picture of their ex shows up in the insular cortex: the same brain area that that's active when you strike a nerve in your tooth, which scientists say is the most extreme physical pain you can feel.

"You obviously don't have a dentist drilling in your tooth, you're not feeling some point in the body that's painful," she says. "But you are feeling the distress that's associated with psychological pain in the same way that you feel distress associated with physical pain."

It's a wound, Brown says, an injury. Not just at a distress level, but a conceptual one.

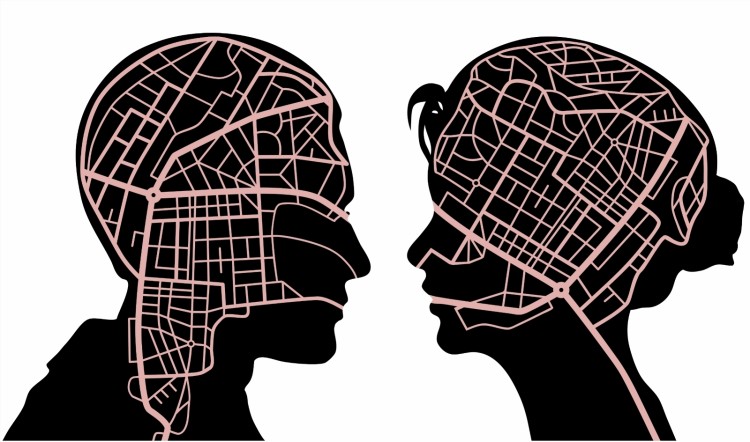

You see, one of things we do when we fall in love (aside from feeling like we're high all the time) is begin to fold the other person into our identity. The "better half," as they say.

Psychologists have a scale for this, called the Integration Into Self Scale. Whether or not you're madly in love with the person you're consciously uncoupling with, you lose part of yourself when you split. You brought them into your sense of who you are - they're your partner after all - and now that half is gone.

"It is like breaking your wrist," Brown says. "You do need to set aside time to take care of it, take care of yourself, but it's time that heals a broken wrist, and it's time that heals this wound of breaking up with someone too." This is terrible news, since after a breakup you're sad all the time and being sad basically sucks.

When sadness isn't totally awfulConfused, I called a Buddhist for help. Susan Piver, who's been teaching meditation for decades and written a bunch of amazing books - including The Wisdom of A Broken Heart, catnip for the crestfallen contemplative - set me straight.

Starting with the following anecdote: The great feminist author and critic Gloria Steinem did a television interview shortly after she lost her husband. The interviewer asked her if she was depressed.

"I'm not depressed," she said. "I'm sad."

The interviewer asked her the difference. "When you're depressed, nothing has any meaning," she replied. "When you're sad, everything does."

Meaning, it turns out, might be the most important thingViktor Frankl, the great Viennese psychologist, postulated that meaning was the most central project of a human life - more than the will to power or pleasure - and that belief helped him survive the concentration camps of Dachau and Auschwitz. He built a whole psychological approach, called logotherapy - coming from logo, the Greek for reason - around helping people to find meaning in their lives.

University of Texas professor James W. Pennebaker has done incredible work with war veterans and other victims of trauma around the power of "expressive writing": if you get people to take the time to write about the traumatic events in their life and thus find meaning in them, they become way physically and mentally healthier.

Meaningful or not, there's much tumult in the first few weeks and months after a breakup. The unbeckoned thoughts of the other person, the slippers of hers that you can't bear to throw out, the restaurant where you had your third date, the text message logs that still show up when you search your phone for the names of friends.

That root canal pain, again and again.

In this way, the memories of the relationship become a being in themselves - perhaps they always were. And that being shows up like an unbidden guest, or to use one of Susan's favorite metaphors, a wild animal - one that will run into your room, tear up all the furniture, and eat all your food.

"You can't yell at it to get it to stop and you can't just leave it alone," she says. "The way to tame it is to just remain calm yourself and just be with it until it calms down."

Another word for "just being with it": meditation"The practice of meditation is not the practice of perfectly following your in breath and your out breath," Piver says. "It's not the practice of success. It's not the practice of health, although these things are all associated with it. It's the practice of friendship and it's the practice of being with yourself in a gentle way. When waves of joy and happiness arise within you, you ride them. When waves of rage and despair arise, you ride those. When waves of boredom and frustration arise, you ride those, too."

This is very useful, given that your - or more specifically, my - mind is a topsy-turvy place to be after a breakup. One of the hallmarks of heartbreak, Piver claims, is obsessiveness: you can't help but wonder if things would have turned out different if you were taller or shorter or more or less sensitive or a better communicator or if you would have said something else in an argument or made your needs more plainly known or cut off all your hair much earlier.

"Your rational mind cannot step in and go, 'stop that,'" Piver says. "The first step in calming this wild animal is just develop some kind of relationship with that obsessiveness so you can begin to calm it."

Without that relationship, you're just on the "holy shit the sky is falling" ride all the time.

But calm doesn't come from telling the wild animal of the broken-hearted discursive mind to shut up. Instead, Piver says the calm comes from sitting down, making space, letting the wild animal go crazy, and watching it subside.

"That watching, that being with, is a statement of power," Susan says. "You are saying 'okay, let me look at this,' as opposed to feeling just completely at the mercy of it. You're taking a seat of power."

With that re-orientation, the heartbreak doesn't feel so overwhelming. You start to have a relationship with the wild-animal-broken-wrist-cocaine-withdrawal.

And I have begun a relationship with mine: when I spot the hat she brought back from Mexico or the mug she gave me on my birthday, I don't cringe quite so much. Instead, I try to stay present with my own waves of exquisite sadness - and stay sensitive to the meaning in all these moments, for the heartbreak, like the relationship, will one day be over, too.

Comment: For a gentle way to ease life's stresses see: Éiriú Eolas, an amazing stress control, healing and rejuvenation program.