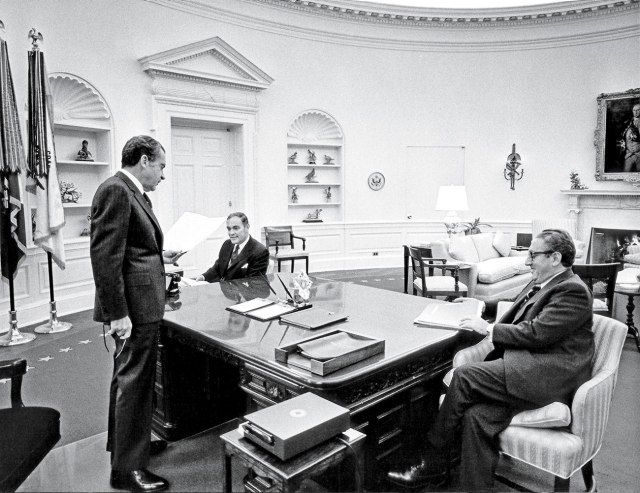

OVAL TEAM: President Richard Nixon with National-Security Adviser Henry Kissinger (right) and Kissinger’s deputy, Alexander M. Haig Jr., 1972.

The result - excerpted below - includes conversations with Nixon's national-security adviser Henry Kissinger, Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman, and chief domestic aide John Ehrlichman is a verbatim narrative of a pivotal period in Nixon's presidency that portrays him as a geopolitical strategist, a crisis manager, and a duplicitous paranoid.

April 28, 1971. During a discussion with Haldeman and Kissinger about an annual youth conference, the subject turned to homosexuality and society.

Nixon: Let me say something before we get off the gay thing. I don't want my views misunderstood. I am the most tolerant person on that of anybody in this shop. They have a problem. They're born that way. You know that. That's all. I think they are. Anyway, my point is, though, when I say they're born that way, the tendency is there. [But] my point is that Boy Scout leaders, YMCA leaders, and others bring them in that direction, and teachers. And if you look over the history of societies, you will find, of course, that some of the highly intelligent people . . . Oscar Wilde, Aristotle, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, were all homosexuals. Nero, of course, was, in a public way, in with a boy in Rome.

Haldeman: There's a whole bunch of Roman emperors. . . .

Nixon: But the point is, look at that, once a society moves in that direction, the vitality goes out of that society. Now, isn't that right, Henry?

Kissinger: Well -

Nixon: Do you see any other change, anywhere where it doesn't fit?

Kissinger: That's certainly been the case in antiquity. The Romans were notorious -

Haldeman: The Greeks.

Kissinger: - homosexuals. . . .

Nixon: The Greeks. And they had plenty of it. . . . By God, I am not going to have a situation where we pass along a law indicating, "Well, now, kids, just go out and be gay." They can do it. Just leave them alone. That's a lifestyle I don't want to touch. . . .

Kissinger: It's one thing for people to, you know, like some people we know, who would do it discreetly, but to make that a national policy . . .

The subject soon turned to swearing in public.

Nixon: I mean, you've got to stop at a certain point. Why is it that the girls don't swear? Because a man, when he swears, people can't tolerate a girl who is a -

Haldeman: Girls do swear.

Nixon: Huh?

Haldeman: They do now.

Nixon: Oh, they do now? But, nevertheless, it removes something from them. They don't even realize it. A man drunk, and a man who swears, people will tolerate and say that's a sign of masculinity or some other damn thing. We all do it. We all swear. But you show me a girl that swears and I'll show you an awful unattractive person. . . . I mean, all femininity is gone. And none of the smart girls do swear, incidentally.

July 6, 1971. Within the administration, Henry Kissinger was Nixon's most valuable strategic partner. But the president sometimes criticized him in private - even to Kissinger's own deputy, Alexander Haig. Among the traits that made Nixon effective in negotiating with adversaries was his suspicious nature, and, ultimately, this extended to his closest colleagues.

Nixon: The thing we've got to do with Henry on this is be very tough on him.

Haig: Exactly. . . .

Nixon: He just can't keep going over [for peace talks on the Vietnam War] and diddling around, because he gets too impressed by the, basically, the cosmetics. He really does. I mean, as much as he's - as realist as he is, you know, it does impress him. . . .

Haig: His background is a problem. He's cut from that goddamn -

Nixon: That's right.

Haig: - left wing . . . even though he's a hardline, tough guy . . .

In a separate conversation - with Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, Nixon's chief domestic aide - the president noted that Kissinger, by inserting himself too often into Middle East policy, might be prompting perceptions of an administration bias toward Israel because of his Jewish heritage.Other conversations captured on the tapes include Nixon speaking about his historic face-to-face meeting with Chairman Mao Zedong; Nixon, Haldeman, and the Reverend Billy Graham talking about world peace; Nixon and Kissinger speculating on Teddy Kennedy's bad behavior; and Nixon discussing his first-term legacy with Haldeman: "A book should be written, called 1972. . . . That would be a hell of a good book."

Nixon: In regard to Henry . . . apparently Newsweek has an article this week that talks about his religious background. . . .

Haldeman: That's what I was saying, Jewish.

Ehrlichman: Jewish.

Nixon: Yeah. . . . He's terribly upset. He feels now that he really ought to resign.... I said, "All right, look, I am just not going to talk about it now. We've got several very big things in the air. Laos, and the possibility of some deal with the Soviets, and SALT [a Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty].... "

What apparently set him all off on this: [the] State [Department] is in the process of preparing a paper on the Mideast [outside of his purview]. If only, God, if Henry could only get, even have that one issue, if he could have that not handled by himself! . . . Anybody who is Jewish cannot handle it. Even though Henry's, I know, as fair as he can possibly be, he can't help but be affected by it. You know, put yourself in his position. Good God! You know, his people were crucified over there. Jesus Christ! And five million of them, popped into bake ovens! What the hell does he feel about all this?

Haldeman: Well, what he ought to recognize is, even if he had no problems at all on it, it's wrong for the country for American policy in the Middle East to be made by a Jew.

Nixon: That's right.

Haldeman: And he ought to recognize that. Because then, if anything goes wrong -

Nixon: That's right.

Haldeman: - they're going to say it's because a goddamn Jew did it rather than blame Americans.

Ehrlichman: We've just been through this on [government policies regarding] health.

Haldeman: Yeah. You, as a Christian Scientist, shouldn't be making health decisions, either.

Ehrlichman: Well, that's why I farmed it out.

At another juncture, Nixon and Kissinger, cautious about U.S. pronouncements that might upset their secret talks with the U.S.S.R., insisted on squelching official American criticism of Russia's oppressive policies against Soviet Jews.

Kissinger: The State Department issued a terrific blast against the treatment of Jews in the Soviet Union.

Nixon: Oh, why - didn't we stop that? Goddamn, I thought we just had that little -

Kissinger: I had thought - I reaffirmed - I may ask you to sign -

Nixon: All right. I'll sign a letter.

Kissinger: - that they - any statement concerning the Soviet Union for the next two months has to be cleared here no matter how trivial.

Nixon: I think you should get the memorandum to me . . . first thing in the morning, Henry. It's so important. . . . I want no statement concerning the Soviet Union of any kind, public statements, to be made without clearance with me.

Haldeman: Unless somebody comes -

Kissinger: With all - you know, I'm Jewish myself, but who are we to complain about Soviet Jews? It's none of our business. If they complain - if they made a public protest to us for the treatment of Negroes, we'd be -

Ehrlichman: Yeah.

Nixon: I know.

Kissinger: You know, it's none of our business how they treat their people.

Still trying to find what Nixon said about homosexuals that implied an "irrational fear or hatred" ("phobia"). He simply stated fact. Or is it hatred now if you point out that the homosexual community suffers from STDs at a rate exponentially greater than the heterosexual community? I hope not. I got that info from a GLBT web site which must otherwise mean they "hate" themselves.