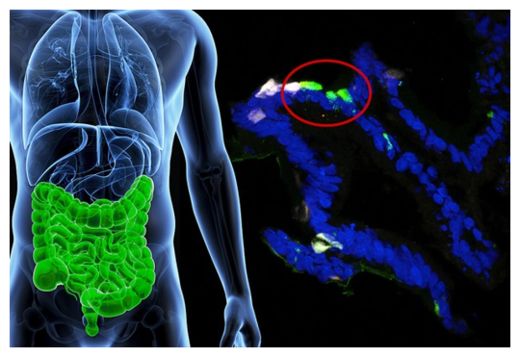

Now, researchers from Columbia University Medical Center have announced the ability to convert cells in the human gastrointestinal tract into insulin-producing cells by simply turning off a single gene, according to a new report in Nature Communications.

"People have been talking about turning one cell into another for a long time, but until now we hadn't gotten to the point of creating a fully functional insulin-producing cell by the manipulation of a single target," said study author Dr. Domenico Accili, a medical professor at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC).

The study team said their finding opens the door to the possibility of treating or curing type 1 diabetes through the reprogramming of existing cells, rather than through transplants or stem cells. Although insulin-producing tissue can be produced in the lab from stem cells, these cells do not yet possess all the capabilities of natural pancreatic beta cells.

Some scientists have instead tried to change present cells in a patient into insulin-producers. Prior research by Columbia scientists transformed mouse intestinal cells into insulin-producing cells; the new study indicates that this method also works in human intestinal cells. The team was able to instruct human gut cells to create insulin in reaction to physiologic conditions by turning off the cells' FOXO1 gene.

The team started their work by developing a tissue replica of the human intestinal tract with pluripotent stem cells. By way of genetic design, they then turned off any working FOXO1 within the intestinal cells. After a week, some of the cells started discharging insulin and, equally vital, only in reaction to glucose.

"By showing that human cells can respond in the same way as mouse cells, we have cleared a main hurdle and can now move forward to try to make this treatment a reality," Accili said.

Co-author Dr. Rudolph L. Leibel, also from CUMC, added, that "this work provides a new research tool for investigating the basic biology underlying the important relationships between the gut and insulin-producing cells, as well as a clear indication of the potential clinical utility of stem cell-based approaches to diabetes."

The team's earlier work with mouse intestinal cells showed that reeducation could lead to healthy blood glucose levels in otherwise diabetic mice.

"Our results show that it could be possible to regrow insulin-producing cells in the GI tracts of our pediatric and adult patients," Accili said at the time.

"Nobody would have predicted this result," Accili added. "Many things could have happened after we knocked out Foxo1. In the pancreas, when we knock out Foxo1, nothing happens. So why does something happen in the gut? Why don't we get a cell that produces some other hormone? We don't yet know."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter