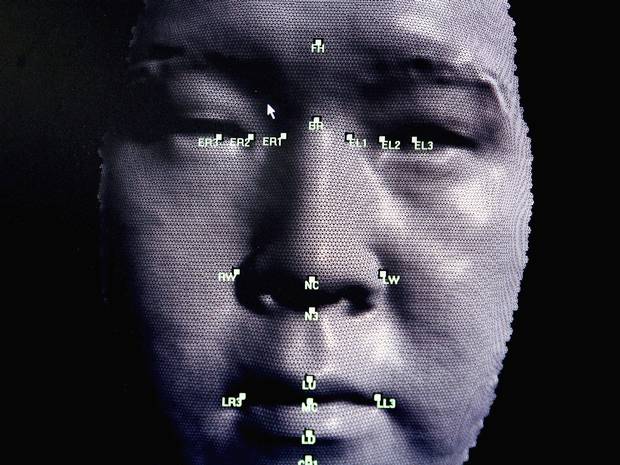

New software will be able to track changes to patients’ features using thousands of photographs.

Between 30 and 40 per cent of genetic disorders - including Down's syndrome and the rare Angelman syndrome - involve some kind of change to the face or skull.

The new software is based on studies of thousands of pictures of previously diagnosed patients, and is able to "learn" what facial features to look for and which to ignore when suggesting a diagnosis.

It will also be able to group together patients with unknown disorders who have similar facial features and skull structures - potentially enabling doctors to identify new disorders, and the DNA variations that cause them.

The software has been developed at Oxford University, in a successful collaboration between medical researchers and the university's Department of Engineering Science.

Using the latest in computer vision technology, the software will "learn" from a growing bank of patient photographs from public and clinical databases. So far, the database extends to nearly 3,000 patients.

While genetic disorders are each individually rare, collectively conditions which may involve some change to face or skull affect one person in 17.

The researchers even used an image of Abraham Lincoln, who is thought to have had a rare condition called Marfan syndrome, characterised by long limbs and fingers, as an example of how the machine could help diagnose the syndrome.

Out of 90 possible disorders, Marfan syndrome emerged as among the 10 most likely when Lincoln's pi cure was analysed.

The new technology is not intended to replace traditional diagnosis, but to assist it, and in some cases improve diagnosis where in parts of the world local clinicians may lack the required expertise.

Dr Christoffer Nellaker, of the Medical Research Foundation's Functional Genomics Unit at Oxford, said that diagnosis of a rare genetic disorder was an important step forward for doctors and patients.

"A doctor should in future, anywhere in the world, be able to take a smartphone picture of a patient and run the computer analysis to quickly find out which genetic disorder the person might have," he said.

"This objective approach could help narrow the possible diagnoses, make comparisons easier and allow doctors to come to a conclusion with more certainty."

The technology was developed in close collaboration with Professor Andrew Zisserman, of Oxford's Department of Engineering Science, and the research is published today in the eLife journal.

Like Google, Picasa and other photo software, it recognises variations in lighting, image quality, background, pose, facial expression and identity. It builds a description of the face structure by identifying corners of eyes, nose, mouth and other features, and compares this against what it has learnt from other photographs fed into the system.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter