Does the scenario sound familiar? It should. For 70 years, the British and Americans have been making heroic movies about World War II, some of which are etched in our culture.

But now for something different: Russian film-makers have got in on the act.

They have created a 3D epic set for the film Stalingrad, about the most famous battle in their history, and the movie has become one of the biggest domestic box office hits of all time. Now, British audiences can see for themselves this amazingly noisy, bloody, cliche-laden, rubble-making version of the war.

3D does startling things to on-screen bomber crashes, tank attacks, ash from burning buildings that appears to float onto the cinema audience.

Half-an-hour into Stalingrad, my lip was curling into cynicism as yet another fearless Russian soldier mowed down yet another battalion of brutish Germans.

But gradually my perception changed: what we were watching was out of almost the same stable as scores of terrific British and American war movies of the past 50 years - such titles as The Guns Of Navarone, Saving Private Ryan, Patton, Battle Of The Bulge, The Battle Of Britain and A Bridge Too Far.

The Russians have staged a late catch-up.

They now feel ready to offer the world a vivid, fiercely nationalistic, deeply sentimental view of their own side of World War II which delights President Vladimir Putin, and is intended to help revive Russian pride, brought low by defeat in the Cold War and the collapse of the old Soviet Union.

We should recall for a moment historical reality, before discussing what the movie makes of it.

The battle for Stalingrad was the turning point of World War II. Following the German invasion of Russia - Operation Barbarossa, which began in June 1941 - the Wehrmacht swept eastwards, destroying whole Soviet armies and capturing two million prisoners, most of whom they starved to death.

In Washington and London, Western warlords asked each other gloomily how long the Russians could stave off absolute defeat.

Allied hopes rose for a time in November and December, when the Red Army checked the Germans in front of Moscow, then launched a counter-offensive which drove them back from the gates of capital.

But in the spring of 1942, Hitler's legions drove deeper into the Russian heartland, besieging St Petersburg, over-running the Crimea, and threatening the oilfields of the Caucasus.

A soldier described bitterly his daily fare in January 1942: one hot meal - cabbage soup with potatoes; half a loaf of bread every two days; some fat; a little cheese and hard honey.

But Hitler was convinced that the Russians were at their last gasp, their reserves exhausted. He was exultant when in June 'Operation Blue' enabled his armies to occupy new swathes of central Russia.

Elsewhere, Rommel was at the gates of Cairo, Admiral Donitz's U-boats were devastating allied shipping, the Japanese wreaking havoc in the Pacific.

Scenting final victory, Hitler deputed General Friedrich Paulus, a staff officer eager to prove himself as a fighting commander, to lead a dash for the city on the Volga that was named after Stalin, and secure a symbolic triumph, while another German army group swung southwards to grab the oilfields.

Hitler's top soldiers were appalled by the perils of splitting the Wehrmacht merely to capture Stalingrad, which was strategically unimportant. Their protests were ignored: the Fuhrer insisted.

Likewise in Moscow, when the German objective became plain, Russia's dictator Josef Stalin gave the order that 'his' city must be held at any cost. Thus the stage was set for one of history's most terrible clashes of arms, in which on the two sides more than a million men became locked in strife between the autumn of 1942 and the following spring.

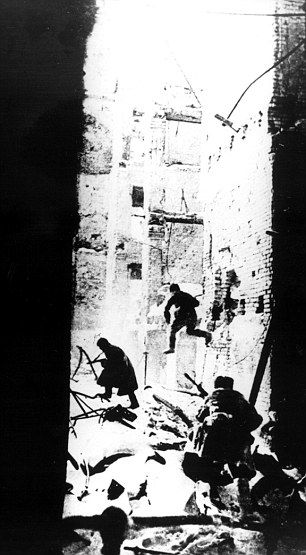

On September 12, the first German troops entered Stalingrad. From the Kremlin came a new order to the Red Army: 'Not a step back . . . The only extenuating circumstance is death.'

The first German air attacks killed between 10,000 and 40,000 people - almost as many as died in the entire London blitz. Shellfire and bombs rained down on the city, day after day and week upon week.

General Vasily Chuikov, commanding Stalin's 62nd Army in the city, wrote: 'The streets of the city are dead. There is not a single green twig on the trees; everything has perished in the flames.'

The concrete masses of the city's transport hubs and industrial plants were swiftly reduced to rubble. Each became a scene of slaughter, engraved on modern Russian legend: the grain elevator beside Number Two station; the freight station; Lazur chemical plant; Red October metal works, and so on.

The Russians initially held a perimeter 30 miles by 18, which shrank relentlessly as Paulus's men thrust forward to within a few hundred yards of the Volga.

Each night, up to three thousand Russian wounded were ferried eastward from the city, while a matching stream of reinforcements, ammunition and supplies reached the defenders.

Both sides were chronically short of food and water. The few surviving civilians suffered terribly, eking a troglodyte existence in cellars.

Yet the nature of the struggle suited the character and virtues of the Russian soldier: dogged and enduring in the most primitive circumstances, where he was expected only to stand his ground, fight, and die.

Chuikov said afterwards: 'Approaching this place, soldiers used to say: "We are entering hell." And after spending one or two days here, they said: "No, this isn't hell, this is ten times worse." '

A young woman soldier wrote: 'I had been imagining what war was like - everything on fire, children crying, cats running about, and when I got to Stalingrad it turned out to be really like that, only more terrible.'

This, then, is the story that film director Fyodor Bondarchuk has set out to tell, focusing upon the fictionalised experience of a few men ordered to hold a vital position between Hitler's army and the vital Volga crossing.

The battle scenes he has created around the house are terrible and convincing. Lest anyone doubt that the reality of Stalingrad was as murderous as the director makes them seem, read this excerpt from the diary of a panzergrenadier officer: 'We have fought for 15 days for a single house with mortars, machine-guns, grenades and bayonets. The front is a corridor between burnt-out rooms.

'The street is no longer measured in metres, but in corpses. When night arrives - one of those scorching, howling, bleeding nights - the dogs plunge into the Volga and swim desperately for the other bank. Animals flee this hell; the hardest stones cannot bear it for long; only men endure.'

I watched Stalingrad with my old friend Antony Beevor, brilliant British chronicler of the battle. He spotted many details that were wrong or unconvincing: a fountain surmounted by a ring of dancing children, a famous landmark of the siege, is shown in the midst of the movie set, far from its real location.

It is absurd to depict Russians watching Germans in the street opposite them, when throughout the battle every visible movement by either side was punished by death.

In the film, the Russian commander reprimands a sniper for killing a German who was fetching water. Yet, in 1942, men killed each other ruthlessly as they ate, slept, washed, prayed.

The cast look absurdly healthy and well-fed; in real Stalingrad almost every man, woman and child was reduced to emaciation.

The cinema Germans - loathsome caricatures to a man - burn to death a Jewish mother and her child in a boarded-up bus.

In reality, murderous as the Nazis were, during that battle they had no time to single out Jews for ritual execution.

In another movie scene, a dying Russian calls in an air strike by radio; but the Red Army had few bombers at Stalingrad, and certainly no forward air control.

Not a word is said in the film about the Stalin regime's savagery, as terrible as that of the Nazis. Unit commissars imposed iron discipline: during the battle 13,500 Russian soldiers were shot by their own side for alleged cowardice or desertion.

Remember the liberties with historical truth taken by the makers of The Dambusters, Reach For The Sky and scores of other movies.

We love none of them less, because we know in our hearts they are no more than half true, or even half plausible. They show the British and American peoples a version of ourselves, or rather of our fathers and grandfathers, that we justly cherish.

The Russians have every reason to commemorate the heroic legend of Stalingrad.

At the core of the film is a big truth: the successful defence of the city proved a critical landmark in the war - much more so than El Alamein or any other British military achievement in the years between the Battle of Britain and D-Day.

When the soundtrack narrator declares that 'Stalingrad changed the course of human history and the fate of our great country', he does not exaggerate.

On November 19, 1942, Georgy Zhukov, the Russian general in charge of the defence of Stalingrad, launched Operation Uranus, a brilliantly conceived pincer movement from north and south of the city, to encircle Paulus's forces.

In the winter fighting of 1942-43, the Germans had lost a million men, while the Red Army now had six million soldiers under arms.

At Stalingrad, when the winter ice melted on the Volga, among a host of horrors revealed by the thaw were the bodies of a Russian and a German, victims of Stalingrad, clasped in a death embrace. Seven decades later, Fyodor Bondarchuk's memorial to their struggle cannot be called a masterpiece of cinema.

But the real-life heroes of the Red Army performed feats of courage and fortitude in 1942 no less remarkable than those so vividly depicted on the 3D screen.

The film is suffused with a blend of brutality and sentimentality which has characterised the Russian psyche for centuries.

Seeing the movie Stalingrad, now in selected British cinemas, may not give you the year's greatest night out, but it will teach you much about how the Russian people see themselves and their wartime heritage.

Now it's entertainment for the masses. How strange that a group of people can sit in front of screen and watch there own kind being killed en masse.

Yes, it is history but unfortunately we don't learn from the past.