* Scientists found bone structure declined after agriculture emerged

* Male farmers 7,300 years ago had legs of cross-country runners

* But just 3,000 years later, they had legs comparable to 'sedentary' students

Mo Farah would have had some tough competition from ancient farmers living 7,300 years ago.

Scientists claim if they were to cross paths, our ancestors would have been capable of outrunning some of the world's most talented athletes.

That's according to recent research by Cambridge University which reveals just how far our fitness has fallen in just a couple of millennia.

The study looked at skeletons dating back to around 5,300 BC with the most recent to 850 AD - a time span of 6,150 years.

It then compared the bones to that of Cambridge University students, and found the leg bones of male farmers 5,300 BC were just as good as those of highly-trained cross-country runners.

But just 3,000 years later, the study found our ancestors had leg bone structures closer to that of the Netflix-watching generation.

When our ancestors made the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agricultural ones, their lower limb strength and overall mobility decreased.

Men were most affected by the change, which suggested a reduction in mobility and loading. In other words, they were covering less distance on foot and carrying out lighter physical tasks.

'My results suggest that, following the transition to agriculture in central Europe, males were more affected than females by cultural and technological changes that reduced the need for long-distance travel or heavy physical work,' said lead researcher Alison Macintosh, from the department of archaeology and anthropology at Cambridge University.

'This also means that, as people began to specialise in tasks other than just farming and food production, such as metalworking, fewer people were regularly doing tasks that were very strenuous on their legs.'

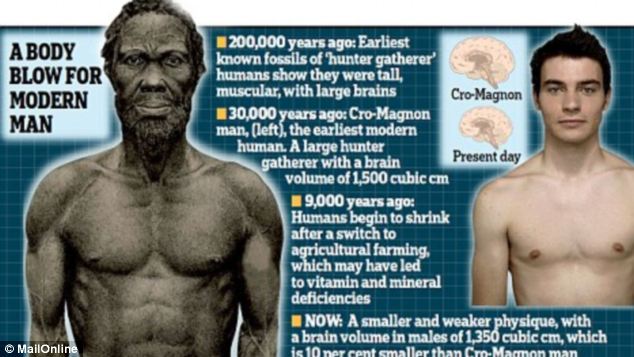

OUR BODIES AND BRAINS ARE SHRINKING - BUT IS FARMING TO BLAME?

An earlier study by Cambridge University found that mankind is shrinking in size significantly.

Experts say humans are past their peak and that modern-day people are 10 per cent smaller and shorter than their hunter-gatherer ancestors.

And if that's not depressing enough, our brains are also smaller.

The findings reverse perceived wisdom that humans have grown taller and larger, a belief which has grown from data on more recent physical development.

The decline, said scientists, has happened over the past 10,000 years. They blame agriculture, with restricted diets and urbanisation compromising health and leading to the spread of disease.

The theory has emerged from studies of fossilised human remains found in Africa, Europe and Asia.

The earliest, from Ethiopia, date back 200,000 years, and were larger and 'more robust' than their modern-day counterparts, said Dr Marta Lahr, an expert in human evolution.

She found that male tibiae became less rigid and the bones of both men and women became less strengthened to loads in one direction more than another.

'Both sexes exhibited a decline in anteroposterior, or front-to-back, strengthening of the femur and tibia through time, while the ability of male tibiae to resist bending, twisting, and compression declined as well,' said Macintosh.

She presented her findings at the annual meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists in Calgary, Canada.

'In central Europe, adaptations in human leg bones spanning this time-frame show that it was initially men who were performing the majority of high-mobility tasks, probably associated with tending crops and livestock.

'But with task specialisation, as more and more people began doing a wider variety of crafts and behaviours, fewer people needed to be highly mobile, and with technological innovation, physically strenuous tasks were likely made easier.

'The overall result is a reduction in mobility of the population as a whole, accompanied by a reduction in the strength of the lower limb bones.'

WHAT CAN BONE STRUCTURE TELL US ABOUT FITNESS?

Human bones are remarkably flexible and respond surprisingly quickly to change.

Put under stress through physical exertion - such as long-distance walking or running - they gain in strength as the fibres are added or redistributed according to where strains are highest.

The ability of bone to adapt to loading is shown by analysis of the skeletons of modern athletes, whose bones show rapid adaptation to both the intensity and direction of strains.

Scientists claim that because the structure of human bones can inform us about the lifestyles of the individuals they belong to, they can provide valuable clues to the lives of our ancestors.

More Darwinism.