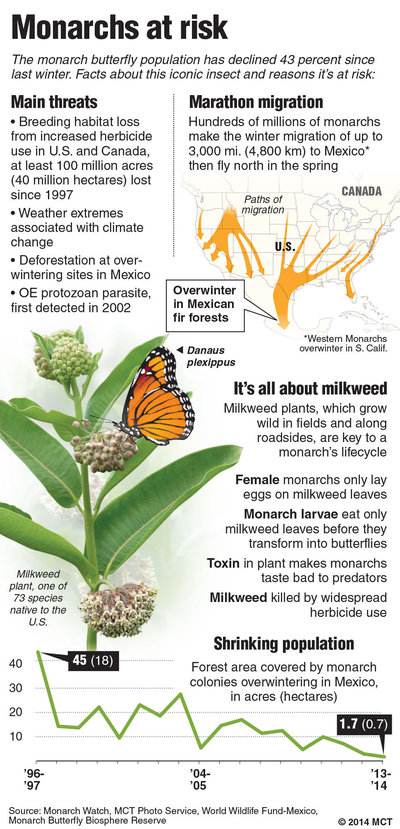

Every year, hundreds of millions of monarch butterflies, each so light that 50 together weigh barely an ounce, find their way on what may be the world's longest insect migration, traveling the length of North America to pass the winter in central Mexico.

Yet the great monarch migration is in peril, a victim of rampant herbicide use in faraway corn and soybean fields, extreme weather, a tiny microbial pathogen and deforestation. Monarch butterfly populations are plummeting. The dense colonies of butterflies on central Mexican peaks were far smaller this year than ever before.

Scientists say Mexico's monarch butterfly colonies, as many as several million butterflies in one acre, are on the cusp of disappearing. If the species were to vanish, one of the few creatures emblematic of all North America, a beloved insect with powerhouse stamina that even school kids can easily identify, would be gone.

"We see these things as so delicate. But if they migrate a distance of some 2,000 miles, from Canada all the way down to Mexico, they are pretty tough," said Craig Wilson, a scientist at Texas A&M University.

The distinctive orange-and-black monarch is enshrined as the state insect or butterfly of Alabama, Idaho, Illinois, Minnesota, Texas, Vermont and West Virginia. It's also the symbol of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which binds Mexico, the United States and Canada.

When President Barack Obama met with Mexico's President Enrique Pena Nieto and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper on Feb. 19 in Toluca, they agreed to establish a working group to ensure the conservation of the monarch butterfly.

Scientists who are studying the monarchs' decline cite many possible reasons, but they're focusing now on one major one: the decline in the United States of milkweed, a lowly broadleaf plant that's widely treated as a weed to be eradicated, doused with herbicides in farmlands and along highway shoulders. Milkweed is most common in the high-grass prairies of the Canadian and U.S. Midwest but its 70 varieties also grow along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, in the Caribbean and elsewhere.

Monarchs can't survive without milkweed.

Female monarchs lay eggs on milkweed. When they hatch, the larvae grow into caterpillars that feed on the milkweed's leaves. Those leaves contain a poison that inoculates the monarchs from their predators. The caterpillars then form chrysalises and emerge as butterflies.

Over the past decade, U.S. fields containing milkweed have declined sharply. Orley "Chip" Taylor, a monarch expert at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, calls the loss "massive."

"We've lost something like 24 million acres because of conversion of land to cropland. That's an area the size of Indiana," he said.

The advent of genetically modified corn and soybean varieties that can withstand herbicides has added to that loss. Now farmers employ glyphosate herbicides, such as Monsanto's Roundup, that kill weeds with a vengeance. It's had a huge impact on milkweed, which before could grow among crops or at the edges of fields.

"The crops survive but any weeds, including milkweed, don't," Wilson said.

Faced with vast reductions in milkweed, the size of the colonies of monarchs escaping northern winters has shrunk radically in central Mexico.

Nearly two decades ago, in the winter of 1996-97, dense monarch colonies covered 44.9 acres of oyamel fir forest. In the 2013-14 winter, the colonies covered only 1.7 acres, a plunge of nearly 44 percent from the previous year. The trend seems inexorable, experts said.

"We must turn the tide for monarchs," said Omar Vidal, the president of WWF-Mexico, a branch of the Switzerland-based World Wide Fund for Nature.

Most monarchs live only a little more than a month. But one generation each year lives seven or eight months, long enough to migrate to central Mexico before winter sets in, where the butterflies settle into a semi-dormant state, often clustering around the same fir trees as their forebears, perhaps drawn by chemical cues. In the spring, the monarchs return to the north, where they lay eggs on milkweed and die, giving way to a new generation.

Other factors may be hurting the monarch population, including extreme conditions associated with climate change. A debilitating protozoan parasite, known in scientific shorthand as OE, also has exploded since 2002 and now affects 10 to 15 percent of monarchs, said Sonia Altizer, an ecologist at the University of Georgia who's studied monarchs for two decades.

While the dwindling monarch colonies worry scientists, who fear they may also be a warning of other environmental crises, in this region of Mexico the decline threatens people's livelihood. Butterfly tourism has grown since scientists first came across the dense winter colonies in 1975.

Indigenous people had long known of the butterflies. The Purepecha people called the monarchs the "souls of the departed" because their arrival in early November coincided with festivals honoring the dead.

"It's not what we expected," said Fernando Guzman Cruz, a member of the El Rosario ejido, or communal agricultural community, that protects the reserve.

Only 55,000 visitors came this season, he said, a "50 percent drop" from a year earlier. He blamed the decline on U.S. agricultural practices hurting the monarch population.

"We want you to stop killing the milkweed," he told a U.S. visitor.

For years, Mexico received much of the blame for dwindling monarch populations. Scientists pointed to rampant illegal logging of the high-altitude oyamel firs the monarch favor. The government took action.

"A year and a half ago, we saw that large-scale logging had been reduced to practically zero," said Vidal of WWF-Mexico. Mexico has done its part.

Now blame has shifted north to the shoulders of U.S. and Canadian farmers and their widespread use of herbicides that kill milkweed.

In the past two centuries, monarchs have spread around the globe to the Pacific Islands, Australia and even parts of Western Europe. So they may never vanish from the world. But they might stop their seasonal movement, going the way of Great Plains bison. Humanity would lose an awe-inspiring annual event if the monarch no longer moves to dense colonies in Mexico, said Taylor, the Kansas expert.

"It's just jaw-dropping," he said. "The sensation of hearing and seeing tens of thousands of cascading butterflies at once is not like any other experience on Earth."

Taylor has been instrumental in the Monarch Waystation program, which encourages people to recolonize areas as small as their yards with milkweed to serve as stopping points for migrating butterflies. More than 7,500 "Waystations" now exist, including 400 in Texas alone, and boosters urge federal and state governments to let milkweed grow undisturbed along highways rather than mow it down.

Despite decades of scientific study, mystery still surrounds the monarch, including how it migrates to the same fir patch colonized by earlier generations.

Some experts worry about a variation of "the butterfly effect," the concept coined by Edward Norton Lorenz, an American meteorologist and pioneer of chaos theory, who suggested that the flapping of a butterfly's wings could trigger a hurricane on the other side of the globe weeks later.

That theory of interdependence now seems turned on its head. The question today is: What occurs when the monarch stops flapping its wings?

"If monarchs are in trouble, and they are a really robust species, you can practically be assured that there are a number of species like pollinators and birds that also are in trouble because they rely on the same habitats as monarchs," Altizer said.

We force things into extinction then try to come-out a hero by trying to 'save' or 'preserve' it. We have DESTROYED much of God's beauty and bounty.