- The sharing of genes is mainly seen in Europeans and may have given an advantage to individuals with Neanderthal variants

- Scientists at Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology don't understand the function of the variants

- But one expert thinks that fatty acids genes were of benefit to Neanderthals and then helped modern Europeans adapt to colder climates

- The same findings were not seen in Asian people though

And now scientists believe that modern Europeans share a number of genes involved in the build-up of certain types of fat with Neanderthals. The same genes were not seen in people from Asia and Africa, however.

It is though that ancient genes might have helped Europeans adapt better to colder climates, giving them an evolutionary advantage.

Neanderthals and modern humans are thought to have co-existed for thousands of years and interbred, meaning Europeans now have roughly 2 per cent Neanderthal DNA.

These 'legacy' genes have been linked to an increased risk from cancer and diabetes by new studies looking at our evolutionary history.

However, it is not all bad news, as other genes we inherited from our species' early life could have improved our immunity to diseases which were common at the time, helping us to survive.

Speaking to MailOnline, professor Chris Stringer, research leader in human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, said: 'We got a quick fix to our own immune system by breeding with Neanderthals which helped us to survive.

'Studies have also already been published which show that humans outside of Africa are more vulnerable to Type 2 diabetes, and that is because we bred with Neanderthals, while those who stayed inside Africa didn't.'

Last year researchers from Oxford and Plymouth universities announced that genes thought to be risk factors in cancer had been discovered in the Neanderthal genome, and in January Nature magazine published a paper from Harvard Medical School suggesting that a gene which can cause diabetes in Latin Americans came from Neanderthals.

'This is the first time we have seen differences in lipid concentrations between populations,' said evolutionary biologist Philipp Khaitovich the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany and the CAS-MPG Partner Institute for Computational Biology in Shanghai, China.

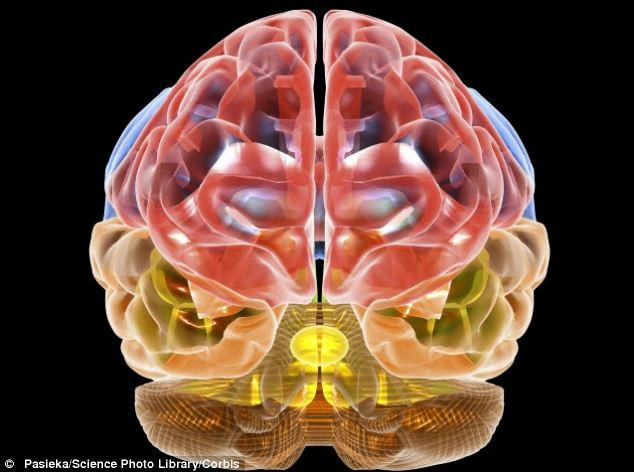

'How our brains are built differently of lipids might be due to Neanderthal DNA.'

In December, scientists at the Max Planck Institute sequenced the genome of Neanderthals and they are now comparing the ancient DNA with modern people.

It is known that Neanderthals interbred with some early humans after they left Africa.

Scientists believe that modern Europeans and Asians have inherited between one per cent and 4 per cent of ancient genomes and they have found that certain versions of these genes are responsible for causing diabetes, Crohn's disease and lupus, Sciencemag reported.

Dr Khaitovich and his team examined the distribution of Neanderthal gene variants in the genomes of 11 populations from Africa, Asia, and Europe.

They discovered that DNA sequences shared between modern humans and Neanderthals are specifically enriched in genes involved in the metabolic breakdown of lipids.

This sharing of genes is seen mainly in contemporary humans of European descent and may have given a selective advantage to the individuals with the Neanderthal variants, they said. The researchers did not find shared genes in Asian and African populations.

Dr Khaitovich said the difference in the number of Neanderthal genes involved in processing lipids was 'huge'.

'These sequences show signs of recent positive selection. This may indicate that they give modern humans carrying the Neanderthal genotype a selective advantage.'

They do not understand the function of the Neanderthal gene variants but in a bid to unlock the mystery they are examining brain tissue from the prefrontal cortex of 14 adults of European, African, and Asian descent, as well as 14 chimpanzees.

Dr Khaitovich believes the Neanderthal genes affect the composition of fat throughout the body but for now, his team is concentrating on looking at brain tissue, mainly because it is easier to obtain from brain tissue banks.

The team are trying to work out exactly what the fatty acids do in the brain and how differences in their concentration might affect its function.

Dr Khaitovich said: 'We think it's a very strong effect with very profound physiological changes. Otherwise, we wouldn't see it in the brain tissue.'

His best guess is that the fatty acid genes were of benefit to Neanderthals and helped modern Europeans adapt to colder environments.

He believes that gene variants might have increased the metabolism to help Europeans and Neanderthals break down fat more quickly to get energy to survive in low temperatures.

'Studies have also already been published which show that humans outside of Africa are more vulnerable to Type 2 diabetes".

Please stop the deception. There are no genes for type 2 diabetes which did not exist until the 1930s and is now deliberately caused by the medical profession and big pharma. There are no genes "for" type 2 diabetes however there are genes which allow the cure of type 2 diabetes. Out of context the decietful line doesn't even mention genes and is like the best deceptions actually true! At least diabetes is more prevalent outside Africa today, Well yes of course it is but I have no doubt the plan is to end this natural situation and proliferate trans fats throughout the dark continent.

Keep taking the blue pill. Do not think. Do not ask questions. Plug yourselves back into the matrix.