Humankind has for centuries been trying to establish how to spot a liar without having to rely on language. The Chinese used to fill a man's mouth with dry rice, on the basis that the pressure of the untruth would interrupt his production of saliva, making the grains attach helpfully to his cheeks and tongue, to announce his mendacity. More recently we've had the polygraph test and, more recently still, voice risk analysis - they're a tiny bit more reliable than the rice, but really, there's not much in it.

They don't work for a number of reasons, but the main one is that they measure stress (on the basis that lying is more stressful than telling the truth). There's a huge variation in how we experience stress. A lot of people find any contact with a stranger stressful, whether they're lying or not; a lot of liars find it really difficult to become stressed, which is how they became delinquent in the first place, just chasing a thrill.

Overall, then, you have built a system in which the most dishonest actually perform pretty well, the least dishonest sometimes perform badly, and in the middle, there might be some whom you assess correctly on a good day.

Everybody knows this about lie detectors and voice risk analysis. A Swedish study from 2007, generally taken as definitive, is actually titled: "Charlatanry in Forensic Speech Science: a problem to be taken seriously." The authors found voice risk analysis to be closer to astrology than science.

Does it matter if a purportedly "scientific" process is actually closer to astrology? There are, after all, plenty of people who still read their star signs. You don't see them being hounded out of public life. Well, not really, no - unless they're spending public money on what is basically a superstitious instrument; which, following a Freedom of Information request by the campaigning group False Economy, it turns out they are.

Despite the fact that the Department for Work and Pensions gave up voice risk analysis software in 2010, very publicly announcing that it didn't work, more than 20 local authorities are still buying it, from Capita, among others.

The Local Government Association justifies the spend on the basis that local authorities detect £200m worth of benefit fraud every year. They sidestep the fact that voice risk analysis doesn't work by saying they'd never convict on that basis alone (which is big of them), and that it's mainly a deterrent. If people think you can tell they're lying, they stop lying. It's a bit like pretending to a field of cows that their fence is electrified.

Two hundred million pounds: sounds a lot, right? Even a council spending a lot of money on bogus software - the London borough of Southwark, for instance, signed a deal with Capita worth £2.5m over three years - could justify it if it were really being stitched up by its citizens. The devil is always in the detail with stories about benefit fraud, which is how the wrong argument keeps winning. Detail is boring at the best of times; if there's anything more boring than a detailed analysis of local government fraud by type, I've yet to meet it.

Nevertheless, this demands attention: in 2010-2011 Southwark detected £213,000 worth of single person's council tax discount fraud, which is why it announced its multimillion-pound "crackdown" in 2012. At that point, it had 53,000 people claiming the single person's discount. In a separate document covering exactly the same year it broke down its households by type and found 40,300 single occupants, plus 17,104 lone parents. In other words, there are over 4,000 more Southwark inhabitants entitled to the discount than are actually claiming it.

So when the borough makes fraud its top priority, it is saying something quite important to the people who live in Southwark, viz: "We are more interested in catching the fraudsters than we are in finding the people who aren't getting what they're entitled to, despite the fact that the second group is almost certainly more populous than the first, and the effects of people paying more than they owe might well be worse for our borough than the effects of people not paying enough." It basically characterises the relationship as one of mutual distrust, rather than mutual support.

This pattern is repeated across local government. The audit commission report on which that £200m figure was based finds that the single largest amount lost to local authorities - hilariously - is through procurement fraud: which is to say, dishonesty in the very contractual process by which they outsource their work to the private sector. Procurement fraud is estimated to have cost local authorities £876m in 2012, and yet in the same year they detected only £1.9m of it; not because it wasn't there, but because they weren't looking. Why weren't they looking? Because businesses don't lie. Only citizens lie.

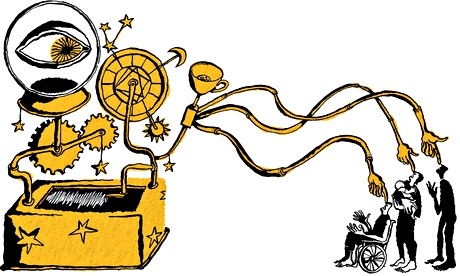

Against this backdrop, the use of voice risk analysis becomes utterly clear, totally rational; it may not be any good at rooting out liars, but that's not the point. The point is the creation of suspicion, the establishment of a code in which the individual habitually lies and the organisation must be always on guard. These are the foundations for authoritarian architecture: this is how institutions are born that accuse you simply because you wouldn't be in that supplicant position if you hadn't, somewhere along the line, done something wrong. What more fitting tool for such a purpose than some science that is really hocus pocus? We should be grateful they don't come round with a handful of rice.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter