Norway, Netherlands and Denmark said they would withhold aid to the Ugandan government in protest against the "draconian law."

On first conviction for so-called homosexual acts, offenders face a 14-year prison sentence. Subsequent convictions for "aggravated homosexuality," which include homosexual acts committed by an HIV-positive person, could bring a penalty of life in prison.

An official at the Norwegian embassy in Kampala said that the measure would immediately affect at least $8 million in aid to Uganda's legal system. Norway extends more than $64 million to Uganda every year. The bulk of western aid has been going directly to the Ugandan government, which would then earmark it for spending in different departments - notably, health, education and the military.

The Netherlands and Denmark said they would redirect nearly $20 million of aid to Ugandan-based private aid agencies and rights groups. The U.S. and Canada, some of the Uganda's largest donors, said they had started reviewing their relationship with Kampala.

The diplomatic moves represented the first fallout of Uganda's controversial antigay bill. Although the bill is politically popular in Uganda, it could cost the government of President Yoweri Museveni. Western donors give up to $2 billion in aid to the country.

"Regrettably, this discriminatory law will serve as an impediment in our relationship with the Ugandan government," Canada's Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird said in a statement Tuesday.

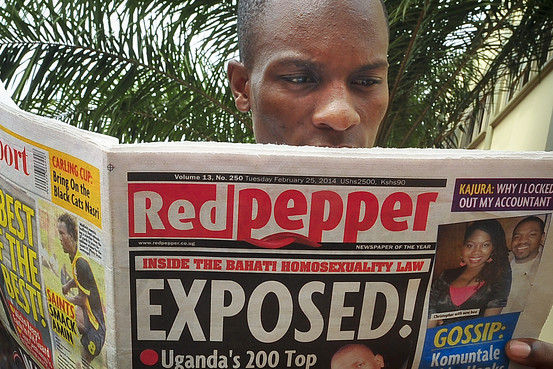

One of Uganda's leading daily newspapers, The Red Pepper, published Tuesday a list of what it called the "country's top 200 homosexuals." The daily listed names of people who have previously not identified themselves as homosexuals.

"The newspapers are inciting the public against homosexuals and unfortunately, government cannot protect us," said Kash Jacqueline, a gay activist in Kampala.

In 2011, a Ugandan tabloid published a list of gay people, sparking a spate of attacks against those perceived as gay across the country. A prominent Ugandan gay activist, David Kato, whose name appeared in the tabloid, was later killed in one of the attacks.

Uganda's antigay bill was passed in December, but Mr. Museveni initially declined to sign it into law, saying that he needed more time to study it. He changed his mind earlier this month, shortly after the lawmakers endorsed him to seek a fifth elective term in office.

Analysts say that Mr. Museveni, who seized power in 1986 following a five-year guerrilla war, was looking for ways to shore up his flagging political support. Most young voters have no memory of the 69-year old president as a freedom fighter.

"Museveni may be tempted by a turn to the well-worn tactic of anticolonial populism," wrote Ben Shepherd, an analyst with U.K.-based Chatham House, in a note Tuesday. "In this context, harsh legislation on sexuality is a relatively easy win."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter