© store.coupstreet.com

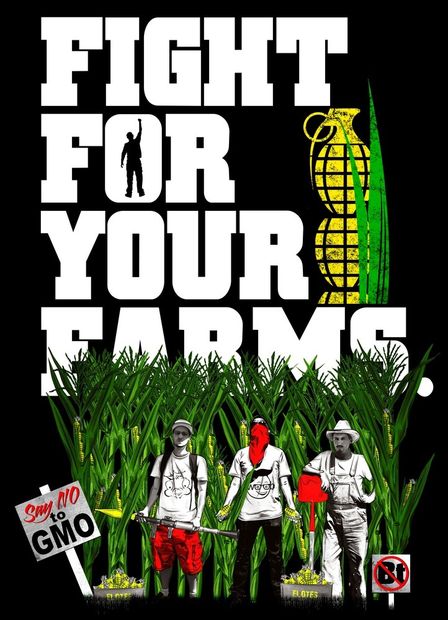

What started out as an effort to keep genetically modified crops out of Benton County appears to be morphing into a fight over community versus corporate rights. It's also part of broader argument that's playing out in other jurisdictions around the state and around the country.

Corvallis-area organic farmers Harry MacCormack, Clint Lindsey and Dana Allen filed paperwork in 2012 for an initiative petition to create the Benton County Local Food System Ordinance. The effort hit several legal roadblocks along the way, with the county clerk ruling three times that the proposed ballot measure did not meet all the legal requirements to be approved for circulation.

But on Jan. 31 the group won a partial victory in Benton County Circuit Court when Judge Locke Williams ruled that the measure had passed the single subject test. Williams is expected to rule soon on a second question regarding the full text of the measure.

If Williams signs off on that issue, the petitioners and their group, the Benton County Community Rights Coalition, could begin gathering signatures to place the initiative on the November ballot.

The measure, if approved, would ban the planting of genetically modified organisms, known as GMOs, or the patenting of seeds anywhere in Benton County.

But it would do much more than that:

The Benton County Local Food System Ordinance also asserts a fundamental "right to self-government" and denies the authority of the state or federal government to overrule its provisions.If passed, that would put the county on a collision course with a new state law, Senate Bill 863, which specifically prohibits local governments from attempting to regulate the use or production of agricultural seed.

Passed in response to several anti-GMO efforts around the state, SB 863 would allow a proposed measure in Jackson County, which qualified for the ballot there before the state law was enacted, to go to a vote. But it would appear to block the Benton County measure and others like it while a governor-appointed task force takes up the question of whether to regulate GMOs statewide.

A line in the sandThe Benton County Community Rights Coalition has its roots, at least in part, in a dispute between specialty seed growers and farmers who want to plant canola, an oilseed crop with promise for the biofuel industry.

The seed growers worried that canola would cross-pollinate with a number of vegetable crops grown in the area. They also feared that GMO canola strains could pass on their genetically engineered traits to non-GMO crops.

Canola had long been excluded from most of the Willamette Valley, but in 2012 the Oregon Department of Agriculture changed the rule to allow it in some areas. The decision set off furious protests from seed growers and their allies, eventually resulting in legislation that restored the old exclusion zone, at least temporarily.

Lindsey was one of the farmers who wanted to be able to plant canola. But after debating the subject with MacCormack, Allen and other local growers, he changed his mind and joined their cause, helping to found the coalition in March 2012.

Now Lindsey sees canola as a symptom of a corporate-dominated agribusiness system that tramples the rights of individual farmers with patented seed lines and genetically modified strains that threaten to pollute natural crops through genetic drift.

"If we don't draw a line in the sand now," Lindsey said, "what you're going to see in five or 10 or 15 years is the erosion of biodiversity and the control of the food system by corporations, taking it out of the hands of farmers."

MacCormack, who owns Sunbow Farm near Philomath and helped found the organic certification agency Oregon Tilth, feels the same way.

"It's a real effort to protect the food system that has been built for 40 years from that particular incursion," he said.

"It's a battle. I have no idea whether we'll be able to win it or not, but we have to do it because what's at stake is people's health."

Revolutionary thinkingThe battle lines extend far beyond Benton County. The anti-GMO ballot measure in Jackson County is slated to go to the voters in May, and a similar measure was on its way to the ballot in Lane County before being held up by a lawsuit.

Citizens in other parts of the state are laying the groundwork for local ordinances to block other actions they find objectionable, from toxic waste dumping to log exports.

Last September, residents of eight Oregon counties came together for a daylong conference in Corvallis. The result was the formation of the Oregon Community Rights Network, made up of representatives from Benton, Jackson, Lane, Lincoln, Marion, Multnomah, Yamhill and Josephine counties.

Invoking the Declaration of Independence to justify the need for a radical restructuring of government, 27 delegates signed a document called the Corvallis Declaration of Community Rights. In a series of clauses beginning "We the people," the group decried the power of corporations and asserted the rights of communities to pass laws protecting local residents from corporate power.

At a second meeting in Eugene on Jan. 25, the fledgling organization adopted bylaws and seated a council of delegates.

"We just got tired of banging our heads on a brick wall that wasn't getting us anywhere," said Allen, who serves as treasurer of the Benton County Community Rights Coalition and attended both meetings of the new statewide network.

"We have joined a movement to exercise our inalienable right to govern ourselves. And it's extremely invigorating ... to know we're doing the right thing."

Similar actions are happening in other parts of the country as well. The Oregon Community Rights Network is aligned with the Community and Environmental Legal Defense Fund, a public interest law firm founded in Pennsylvania in 1995.

To date, CELDF has helped draft more than 160 local ordinances in 10 states aimed at curtailing a wide range of corporate activities, from factory farming and commercial water withdrawals to sludge dumping and fracking.

These laws arise from what Kai Huschke, CELDF's Spokane-based organizer for the Northwest, calls a "visceral" anger over the actions of big companies and frustration over the ability of state and federal laws to pre-empt local decisions.

"It's really an evolution of this idea to constitutionally recognize this right to self-governance and also this notion that corporations have more rights than individuals," Huschke said.

"When you show up in a community where the water can't be drunk because of hydraulic fracturing, it becomes pretty simple for folks."

Testing the theoryNone of these laws has been tested in court so far, but the pushback has already begun.

John Reerslev, who farms about 2,000 acres near Junction City with his brothers, has filed suit to block the proposed anti-GMO measure in Lane County.

Reerslev grows genetically engineered sugar beets for seed on a portion of his acreage, and he's convinced the GMO traits in his beets are incapable of jumping to other crops because of the way they're designed. He's also confident that local buffer zones are enough to prevent cross-pollination.

For him, the lawsuit is about defending his right to farm his own land.

"I have two brothers and my family and their families and a number of employees who depend on the revenue we can produce on our farm," Reerslev said.

"I understand a lot of people are leery of the new technologies we employ, but that's what we have, and if it's not produced here it's going to be produced in some other county or some other state. I don't want to miss out on the opportunity."

The Oregon Farm Bureau has joined Midwest sugar beet growers to oppose the Jackson County initiative and will fight efforts to pass similar measures elsewhere, said Katie Fast, the organization's vice president for public policy.

"It's really setting a standard where local governments that don't have the expertise or the resources are regulating agriculture," Fast said.

"For our members, their farms don't stop at political boundaries," she added. "If you have different regulations depending on what county you're in, that kind of puts you in a bind."

Oregonians for Food and Shelter, a farm advocacy group, has the same objections.

"We think county-by-county policymaking for agriculture in our state is a very bad method of policymaking," said the group's executive director, Scott Dahlman.

"We are definitely opposed to the county measures, and we'll do everything we can to keep those from happening."

And even if voters approve the local measures, Dahlman said, SB 863 should keep them (with the exception of Jackson County's) from taking effect.

"Now that that's passed, it would be pre-empted," he said.

Don't be too sure about that, says Ann Kneeland, a Eugene attorney representing the anti-GMO petitioners in both Lane and Benton counties.

Both measures, she said, are grounded in the bedrock constitutional principle that the people have the right to govern themselves. While the community rights doctrine has not yet faced a full-fledged legal test, she thinks it could hold up in court.

"It's definitely a radical concept, but it hearkens back to the founding of this country," Kneeland said. "It's democracy as it was really intended."

On the NetTo learn more about the Benton County Community Rights Coalition or read the text of the proposed ballot measure, go

here

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter