The Akademik Shokalskiy was trapped in thick ice for 10 days

BBC producer Andrew Luck-Baker was on board a Russian research vessel when it became trapped in pack ice over Christmas. Here, Andrew, who was covering an expedition for the BBC World Service's Discovery programme, examines the events that led up to the ship being stranded.

As the members of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) reach the end of their travels together, investigations will soon begin to establish why their Russian expedition ship, the MV Akademik Shokalskiy, became trapped in thick and extensive pack ice for 10 days.

The ship's entrapment at Christmas time led to an Australian icebreaker being diverted from its own operations hundreds of kilometres along the coast and a Chinese icebreaker also coming to the rescue.

That vessel ended up stuck in the ice itself for many days. A smaller French icebreaker ship was also summoned to the scene. It retreated when it became clear that the ice was much too thick for it to help.

The 52 members of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition were trapped until 2 January when a helicopter team from the Chinese vessel airlifted the scientists, tourists and operational staff to the Aurora Australis.

The expedition leaders could have some tough questions to face about logistical shortcomings that may have put the vessel at increased risk of becoming trapped. These were operational errors and mishaps during a visit by scientists and tourists to a location close to the Antarctic shore on 23 December.

Ship insurance companies along with the Australian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre will be keen to establish what happened and whether human error contributed to the Akademik Shokalskiy becoming encased.

In the thrilling environment of the islands, it was easy to lose track of time, says Andrew

The enquiries will address whether it was prudent to take the Shokalskiy into an area close to the East Antarctic shore, known as La Motte Bay on 23 December.

They are also likely to cover whether the logistics around an excursion on the ice that day were organised such that the ship's captain Igor Kiselev could evacuate the ship, crew and passengers as quickly as he saw fit and ordered.

The vessel's entrapment happened at the end of the AAE's final intended day at the Antarctic coast. The expedition leaders were keen to get some of their scientists and accompanying tourist assistants to a small cluster of rocky hillocks called the Hodgeman Islands, close to land.

The islands rise out of what's called fast ice - a margin of persistent ice between the land and the water's edge.

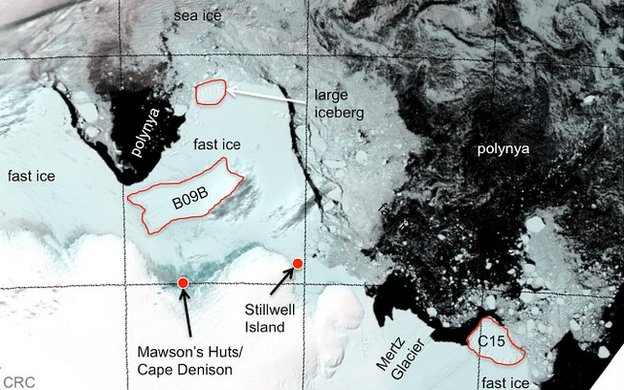

Travelling eastwards and then southwards, the Shokalskiy took a route through a relatively clear patch of water, called the Mertz polynya.

A polynya is an area of water kept relatively clear - much of the time - of sea ice, by a particular kind of polar wind. This katabatic wind blows pretty persistently towards the coast from the polar plateau in the continent's interior. However, routes through polynyas can close within a few hours if the distribution of sea ice in the general area changes with shifts in the wind direction and speed.

The Shokalskiy began to run into trouble towards the end of that day as it attempted to leave the area. Its location was close to the edge of a huge glacial system called the Mertz Glacier where it flows into the sea. Four years ago, the end of this glacier was smashed into many pieces by a gigantic passing iceberg named B09B.

Expedition leader Chris Turney, a professor of earth sciences at the University of New South Wales, said that the ice floes that surrounded his ship appeared to have come from the eastern side of the wrecked glacier front.

"It seems to have been coming from the other side of the Mertz glacier. This was very thick ice - three plus metres thick which was coming across (our path)," he said.

"The captain did an amazing job, weaving a course trying to get out but it was quite clear this was a different event from anything we'd seen before."

'Little warning'The captain and crew realised they were surrounded and stuck fast by Christmas Eve, 24 December. Chris Turney estimates that open water lay just two nautical miles ahead. However, by that point, with the ice so thick and more floes accumulating around and ahead of us, clear water might as well have been 20 nautical miles away. Within a couple of days, it was in fact that distance to open water.

On Christmas Day, the captain issued an international distress call, not only because his ship was stuck fast but because there were large icebergs moving on currents in the area on trajectories that were potentially dangerous to the ship.

Chris Turney said: "It looks like it was fast ice attached to the continent on the other side of the Mertz glacier and, for whatever reason, it was broken up and with strong southeasterly winds, chunks of ice were driven across our path. It was one of those events which happens occasionally (and with little warning). We were unfortunate enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time."

In the opinion of Murray Doyle, the captain of the rescue vessel, the Aurora Australis, the conditions around the Mertz glacier were typical of those seen in the past few years.

Andrew's party prepares to leave the Hodgeman Islands

He told the Sydney Morning Herald: "Since the Mertz Glacier was punched out by the B09B (glacier) some years ago, it has changed the whole dynamics in the area".

Significant sized floes build up year after year, he said.

The Akademik Shokalskiy was receiving sea-ice satellite data and weather forecasts on the area. Expedition co-leader Greg Mortimer said in an interview with the BBC that "the ice situation was very unexpected and (ran) counter to what we had seen on the most recent ice charts and weather forecasts we had".

He added: "With the information and observations that we had at the time and the decisions we made based on that, they were reasonable, good decisions. But it was a difficult situation that needed to be treated with great care."

However, another source with considerable nautical knowledge of East Antarctica said that "with the weather forecast" as it was that day, "this was not a good place to be".According to Tony Press, head of the Antarctic Climate and Ecosystem Coordinated Research Centre in Tasmania:

"It's incumbent on the vessel to understand the environment in which it's in, from the point of view of sea-ice conditions and weather conditions. They need to plan accordingly and have an exit strategy which can be executed in timely fashion if the conditions become threatening."Investigations are bound to examine whether the escape strategy the captain had was put in jeopardy by the less than perfectly executed operations taking people between the ship and the Hodgeman islands, some 8km away, and the management of those individuals while they were on the islands.

In a report he has compiled in consultation with other senior expedition personnel, Greg Mortimer has identified several weak points in the ice-side logistics. These were the responsibility of the expedition team, not Captain Kiselev.

"There was a delay of a couple of hours on extracting people from the ice on the Hodgeman Islands and getting them on to the ship to leave the area. The delays may or may not have led to us getting stuck," said Greg Mortimer.

"During the period of people being on shore at the Hodgeman islands, the Russian captain said the ice is starting to close around us at which point we hit the evacuation button."

This was at about 14:30 ship time (01:30 GMT) on 23 December, according to Greg Mortimer. Despite the captain's mounting frustration and anger over the situation, the Shokalskiy was ready to leave almost four hours later, at 18:15 ship time (05:15 GMT). Greg Mortimer agrees that this was an excessively long time.

The Akademik Shokalskiy became stuck in the region around the Mertz Glacier

Mortimer believes that the most important logistical failure was a communication breakdown between the ship and the expedition leaders and operations team on the ice, at the Hodgeman Islands.

As a result, says the Antarctic expedition veteran of 20 years: "The initial message to evacuate the area was not heard by some key people. We had patchy VHF radio contact. This [patchiness] could have been down to the distance from the ship to the islands. [The hand-held radios] were at the limit of their range at 8km away. We did have satellite phones but satellite phone contact wasn't made."

For whatever reason, people on the ice appear not to have responded to satellite phone calls made from the bridge.

The poor communication between ship and the ice was compounded by what many regarded as less than perfect management of the numbers of visitors to the islands. Most of the visitors were of the paying passenger contingent of the expedition - people who had no experience of Antarctica and its hazards.

Controversial pointsI was in the first group to leave the ship at about 13:00 ship time (midnight GMT on 23 December), and take a short zodiac journey across the water to the ice edge.

The excursion was already a couple of hours behind schedule. This was because one of the three all-terrain amphibious vehicles called argos that were to take us to the islands had earlier flooded with water while it was transported from the ship to the ice edge.

Once our group was on the ice, the 12 of us were divided among two quad bikes and two argos. Then we were driven to the Hodgeman Islands in a strong southerly wind which blew drift up into the air, creating a hazy visibility.

We were told that we would have a maximum of one hour at the islands, after the 20 minute drive to the site. Then we would have to be ready to return on the vehicles bringing the next party. This sounded like an efficient system of relaying teams back and forth between ship and the islands.

The last convoy of vehicles returns to the Shokalskiy

However, there was a lack of organisation to supervise and enforce it. A number of us were at the islands for about two hours, having wandered off in small groups with the scientist whose work we were particularly interested in.

In the thrilling environment in which we now found ourselves, it was easy to lose track of time. We were surrounded by Adelie penguins and Weddell seals, and the white cliffs of the great East Antarctic Ice Sheet towered high with both beauty and menace, in the middle distance.

So, for example, when the vehicles arrived with the second party of visitors, there were only three people at the pick-up area ready to return to the ship.

One of those returnees was a female tourist who had fallen into freezing seawater through a snow-concealed tidal crack in the fast ice. She was wet up to waist height and needed to be transported back to the ship as quickly as possible.

Timing issueThe difficulty was there were too many people and not enough seats on the argos and quad bikes to take everyone back in one convoy - even when these vehicles were carrying one more passenger than they were designed to.

As a result, Chris Turney remained behind with three of the youngest male members of the expedition (two tourists and an expedition paramedic). Turney warned them that the four of them might have to use the emergency tent and supplies - if the captain of the Shokalskiy decided to pull the vessel out once the previous convoy of people had arrived.

Fortunately for the final four, the Shokalskiy hung on at its mooring site and an argo went back to the islands to pick them up.

Greg Mortimer is currently refusing to say whether he believes the various ice-side mistakes led to the Shokalskiy being beset by the pack ice a few hours later.

"We got stuck - which in my mind means we got it wrong. It was down to circumstance. I find that quite tough to take because what I like to do is read those circumstances (correctly)," he explained.

Chris Turney does not think the expedition's visit to the islands was unduly long. Neither does he believe that the length of time spent there had any bearing on the Shokalskiy being in the wrong place at the wrong time when the ice surrounded and blocked her in.

It may not be provable either way. Whatever the truth, some of the paying passengers on the Australasian Antarctic Expedition 2013 spoke unfavourably about the manner in which the situation at the islands was handled. Everyone I spoke to asked to be quoted anonymously, mindful of the considerable media interest that may await in Tasmania.

"The teacher in me cringes at the logistics," said one of the paying members of the expedition.

Another said the expedition was run like a "boys' own adventure" and expressed concern over what she believed was a lack of thorough briefing on safety procedures throughout the Antarctic leg of the expedition.

Others I spoke to agreed that the expedition had its shortcomings in the logistics department.

However, Terry Gostlow, a resident of Adelaide, said he wanted to praise expedition leader Chris Turney for mounting a privately funded Antarctic scientific expedition of which members of the public could be part and in which they could actively contribute as scientific assistants, if they chose.

Mr Gostlow said he applauded this as a way of making science exciting and taking Antarctic research to the people.

John Black of Sydney agreed, saying that it would be a pity if future privately-run science expeditions were not permitted by the Australian government's Antarctic authorities because of how events unfolded during the Australasian Antarctic Expedition 2013.

The outreach mission of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition was one of the features which attracted several of the participating scientists to sign up.

The coming investigations may now take a view on whether an expeditionary cocktail of working Antarctic scientists and accompanying tourists is a viable formula in an environment as unpredictable and dangerous as Antarctica.

Having had to accompany investors to the mines I worked at, there is a reason such endeavors are referred to as "Dog and Pony" shows. Dawdling, fiddling with things not understood and wandering has to be curtailed by strict instructions before going underground, and constant accompaniment. Whomever was in charge of the land side of the visit didn't do their job, and that's my final opinion. Make a mistake, and you don't get a second chance. Antarctica is no place for tourists or agendists.