What possible connection could there have been between George H.W. Bush and the assassination of John F. Kennedy? Or between the C.I.A. and the assassination? Or between Bush and the C.I.A.? For some people, apparently, making such connections was as dangerous as letting one live wire touch another. Here, in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination in November, is the first part of a ten-part series of excerpts from WhoWhatWhy editor Russ Baker's bestseller, Family of Secrets: The Bush Dynasty, America's Invisible Government and the Hidden History of the Last Fifty Years. The story is a real-life thriller.

Note: Although these excerpts do not contain footnotes, the book itself is heavily footnoted and exhaustively sourced. (The excerpts in Part 1 come from Chapter 2 of the book, and the titles and subtitles have been changed for this publication.)

Poppy's Secret

When Joseph McBride came upon the document about George H. W. Bush's double life, he was not looking for it. It was 1985, and McBride, a former Daily Variety writer, was in the library of California State University San Bernardino, researching a book about the movie director Frank Capra. Like many good reporters, McBride took off on a "slight," if time-consuming, tangent - spending day after day poring over reels of microfilmed documents related to the FBI and the JFK assassination. McBride had been a volunteer on Kennedy's campaign, and since 1963 had been intrigued by the unanswered questions surrounding that most singular of American tragedies.

A particular memo caught his eye, and he leaned in for a closer look. Practically jumping off the screen was a memorandum from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, dated November 29, 1963. Under the subject heading "Assassination of President John F. Kennedy," Hoover reported that, on the day after JFK's murder, the bureau had provided two individuals with briefings. One was "Captain William Edwards of the Defense Intelligence Agency." The other: "Mr. George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency."

To:McBride shook his head. George H. W. Bush? In the CIA in 1963? Dealing with Cubans and the JFK assassination? Could this be the same man who was now vice president of the United States? Even when Bush was named CIA director in 1976 amid much agency-bashing, his primary asset had been the fact that he was not a part of the agency during the coups, attempted coups, and murder plots in Iran, Cuba, Chile, and other hot spots about which embarrassing information was being disclosed every day in Senate hearings.

Director

Bureau of Intelligence and Research

Department of State

[We have been] advised that the Department of State feels some misguided anti-Castro group might capitalize on the present situation and undertake an unauthorized raid against Cuba, believing that the assassination of President John F. Kennedy might herald a change in U.S. policy... [Our] sources know of no [such] plans... The substance of the foregoing information was orally furnished to Mr. George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency and Captain William Edwards of the Defense Intelligence Agency.

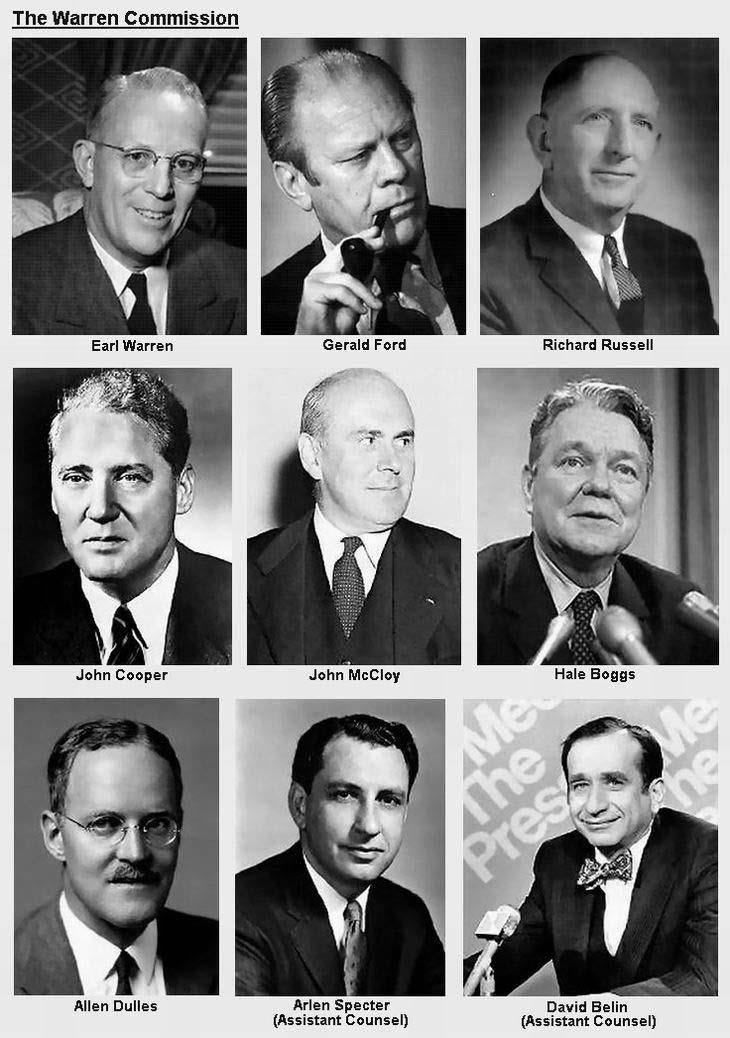

For CIA director Bush, there had been much damage to control. The decade from 1963 to 1973 had seen one confidence-shaking crisis after another. There was the Kennedy assassination and the dubious accounting of it by the Warren Commission. Then came the revelations of how the CIA had used private foundations to channel funds to organizations inside the United States, such as the National Student Association. Then came Watergate, with its penumbra of CIA operatives such as E. Howard Hunt and their shadowy misdoings. Americans were getting the sense of a kind of sanctioned underground organization, operating outside the law and yet protected by it. Then President Gerald Ford, who had ascended to that office when Richard Nixon resigned, fired William Colby, the director of the CIA, who was perceived by hard-liners as too accommodating to congressional investigators and would-be intelligence reformers.

Now Ford had named George H. W. Bush to take over the CIA. But Bush seemed wholly unqualified for such a position - especially at a time when the agency was under maximum scrutiny. He had been U.N. ambassador, Republican National Committee chairman, and the U.S. envoy to Beijing, where both Nixon and Henry Kissinger had regarded him as a lightweight and worked around him. What experience did he have in the world of intelligence and spying? How would he restore public confidence in a tarnished spy agency? No one seemed to know. Or did Gerald Ford realize something most others didn't?

Bush served at the CIA for one year, from early 1976 to early 1977. He worked quietly to reverse the Watergate-era reforms of CIA practices, moving as many operations as possible offshore and beyond accountability. Although a short stint, it nevertheless created an image problem in 1980 when Bush ran unsuccessfully for the Republican presidential nomination against former California governor Ronald Reagan. Some critics warned of the dangerous precedent in elevating someone who had led the CIA, with its legacy of dark secrets and covert plots, blackmail and murder, to preside over the United States government.

"Must be another George Bush"

In 1985, when McBride found the FBI memo apparently relating to Bush's past, the reporter did not immediately follow up this curious lead. Bush was now a recently reelected vice president (a famously powerless position), and McBride himself was busy with other things. By 1988, however, the true identity of "Mr. George Bush of the CIA" took on new meaning, as George H. W. Bush prepared to assume his role as Reagan's heir to the presidency. Joe McBride decided to make the leap from entertainment reportage to politics. He picked up the phone and called the White House.

"May I speak with the vice president?" he asked

McBride had to settle for Stephen Hart, a vice presidential spokesman. Hart denied that his boss had been the man mentioned in the memo, quoting Bush directly. "I was in Houston, Texas, at the time and involved in the independent oil drilling business. And I was running for the Senate in late '63. I don't have any idea of what he's talking about." Hart concluded with this suggestion: "Must be another George Bush."

McBride found the response troubling - rather detailed for a ritual non-denial. It almost felt like a cover story that Bush was a bit too eager to trot out. He returned to Hart with more questions for Bush:

- Did you do any work with or for the CIA prior to the time you became its director?

- If so, what was the nature of your relationship with the agency, and how long did it last?

- Did you receive a briefing by a member of the FBI on anti-Castro Cuban activities in the aftermath [of] the assassination of President Kennedy?

Undeterred, McBride called the CIA. A spokesman for the agency, Bill Devine, responded: "This is the first time I've ever heard this . . . I'll see what I can find out and call you back."

The following day, the PR man was tersely formal and opaque: "I can neither confirm nor deny." It was the standard response the agency gave when it dealt with its sources and methods. Could the agency reveal whether there had been another George Bush in the CIA? Devine replied: "Twenty-seven years ago? I doubt that very much. In any event, we have a standard policy of not confirming that anyone is involved in the CIA."

"Apparently" George William Bush

But it appears this standard policy was made to be broken. McBride's revelations appeared in the July 16, 1988, issue of the liberal magazine the Nation, under the headline "The Man Who Wasn't There, 'George Bush,' C.I.A. Operative." Shortly thereafter, CIA spokeswoman Sharron Basso told the Associated Press that the CIA believed that "the record should be clarified." She said that the FBI document "apparently" referred to a George William Bush who had worked in 1963 on the night shift at the Langley, Virginia, headquarters, and that "would have been the appropriate place to have received such an FBI report." George William Bush, she said, had left the CIA in 1964 to join the Defense Intelligence Agency.

Certainly, the article caused George H. W. Bush no major headaches. By the following month, he was triumphantly accepting the GOP's presidential nomination at its New Orleans convention, unencumbered by tough questions about his past.

CIA can't find "other" George Bush?

Meanwhile, the CIA's Basso told reporters that the agency had been unable to locate the "other" George Bush. The assertion was reported by several news outlets, with no comment about the irony of a vaunted intelligence agency - with a staff of thousands and a budget of billions - being unable to locate a former employee within American borders.

Perhaps what the CIA really needed was someone like Joseph McBride. Though not an investigative journalist, McBride had no trouble finding George William Bush. Not only was the man findable; he was still on the U.S. government payroll. By 1988 this George Bush was working as a claims representative for the Social Security Administration. He explained to McBride that he had worked only briefly at the CIA, as a GS-5 probationary civil servant, analyzing documents and photos during the night shift. Moreover, he said, he had never received interagency briefings.

Several years later, in 1991, former Texas Observer editor David Armstrong would track down the other person listed on the Hoover memo, Captain William Edwards. Edwards could confirm that he had been on duty at the Defense Intelligence Agency the day in question. He said he did not remember this briefing, but that he found the memo plausible in reference to a briefing he might have received over the phone while at his desk. While he said he had no idea who the George Bush was who also was briefed, Edward's rank and experience was certainly far above that of the night clerk George William Bush.

Shortly after McBride's article appeared in the Nation, the magazine ran a follow-up op-ed, in which the author provided evidence that the Central Intelligence Agency had foisted a lie on the American people. The piece appeared while everyone else was focusing on Bush's coronation at the Louisiana Superdome. As with McBride's previous story, this disclosure was greeted with the equivalent of a collective media yawn. An opportunity was bungled, not only to learn about the true history of the man who would be president, but also to recognize the "George William Bush" diversion for what it was: one in a long series of calculated distractions and disinformation episodes that run through the Bush family history.

George William Bush Deposes

With the election only two months away, and a growing sense of urgency in some quarters, George William Bush acknowledged under oath - as part of a deposition in a lawsuit brought by a nonprofit group seeking records on Bush's past - that he was the junior officer on a three- to four-man watch shift at CIA headquarters between September 1963 and February 1964, which was on duty when Kennedy was shot. "I do not recognize the contents of the memorandum as information furnished to me orally or otherwise during the time I was at the CIA," he said. "In fact, during my time at the CIA, I did not receive any oral communications from any government agency of any nature whatsoever. I did not receive any information relating to the Kennedy assassination during my time at the CIA from the FBI. Based on the above, it is my conclusion that I am not the Mr. George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency referred to in the memorandum." . . .

George H.W. Bush: Spy from the age of 18

Almost a decade would pass between Bush's election in 1988 and the declassification and release in 1996 of another government document that shed further light on the matter. This declassified document would help to answer some of the questions raised by the '63 Hoover memo - questions such as, "If George Herbert Walker Bush was already connected with the CIA in 1963, how far back did the relationship go?"

But yet another decade would pass before this second document would be found, read, and revealed to the public. Fast-forward to December 2006, on a day when JFK researcher Jerry Shinley sat, as he did on so many days, glued to his computer, browsing through the digitized database of documents on the Web site of the Mary Ferrell Foundation.

On that December day, Shinley came upon an internal CIA memo that mentioned George H. W. Bush [the Bush designated Director of Central Intelligence (DCI)]. Dated November 29, 1975, it reported, in typically spare terms, the revelation that the man who was about to become the head of the CIA actually had prior ties to the agency. And the connection discussed here, unlike that unearthed by McBride, went back not to 1963, but to 1953 - a full decade earlier. Writing to the chief of the spy section of the analysis and espionage agency, the chief of the "cover and commercial staff" noted:

Through Mr. Gale Allen . . . I learned that Mr. George Bush, DCI designate has prior knowledge of the now terminated project WUBRINY/LPDICTUM which was involved in proprietary commercial operations in Europe. He became aware of this project through Mr. Thomas J. Devine, a former CIA Staff Employee and later, oil-wildcatting associate with Mr. Bush. Their joint activities culminated in the establishment of Zapata Oil [sic] [in 1953] which they eventually sold. After the sale of Zapata Oil, Mr. Bush went into politics, and Mr. Devine became a member of the investment firm of Train, Cabot and Associates, New York . . . The attached memorandum describes the close relationship between Messrs. Devine and Bush in 1967-1968 which, according to Mr. Allen, continued while Mr. Bush was our ambassador to the United Nations.In typical fashion for the highly compartmentalized and secretive intelligence organization, the memo did not make clear how Bush knew Devine, or whether Devine was simply dropping out of the spy business to become a true entrepreneur. For Devine, who would have been about twenty-seven years old at the time, to "resign" at such a young age, so soon after the CIA had spent a great deal of time and money training him was, at minimum, highly unusual. It would turn out, however, that Devine had a special relationship allowing him to come and go from the agency, enabling him to do other things without really leaving its employ. In fact, CIA history is littered with instances where CIA officers have tendered their "resignation" as a means of creating deniability while continuing to work closely with the agency.

Devine's role in setting up Zapata would remain hidden for more than a decade - until 1965. At that point, as Bush was extricating himself from business to devote his energies to pursuing a congressional seat, Devine's name suddenly surfaced as a member of the board of Bush's spin-off company, Zapata Offshore - almost as if it was his function to keep the operation running. To be sure, he and Bush remained joined at the hip.

Devine, like the senior George Bush, is now in his eighties and still active in business in New York. When I reached him in the winter of 2007 and told him about recently uncovered CIA memos that related both his agency connections and his longtime ties to Bush, he uttered a dry chuckle, then continued cautiously.

"Tell me who you are working with in the family," he asked when I informed him I was working on a book about the Bushes. I explained that the book was not exactly an "authorized" biography, and therefore I was not "working" with someone in the family. Moreover, I noted, the Bushes were not known for their responsiveness to journalistic inquiries. "The family policy has been as long as George has been in office, they don't talk to media," Devine replied. But he agreed to contact the Bush family seeking clearance. "Well, the answer is, I will inquire. I have your telephone number, and I'll call you back when I've enquired."

Surprisingly enough, he did call again, two weeks later, having checked in with his old friend in Houston. He explained that he had been told by former president George H.W. Bush not to cooperate. When I spoke to him several months later, he still would not talk about anything - though he did complain that, thanks to an article I had written about him for the Real News Project, he was now listed in Wikipedia. And then he did offer a few words:

Thomas Devine: I just broke one of the first rules in this game.In fact, Devine had little to complain about. At the time, although I was aware that he seemed to be confirming that he himself had been in the "game," I did not understand the full extent of his activities in conjunction with Bush. Nor did I understand the heightened significance of their relationship during the tumultuous event of 1963, to be discussed in subsequent chapters.

Russ Baker: And what is that?

Thomas Devine: Do not complain.

No Business like the Spy Business

Before there was an Office of Strategic Services (July 1942-October 1945) or a Central Intelligence Agency (founded in 1947), corporations and attorneys who represented international businesses often employed associates in their firms as private agents to gather data on competitors and business opportunities abroad. So it was only to be expected that many of the first OSS recruits were taken from the ranks of oil companies, Wall Street banking firms, and Ivy League universities and often equated the interests of their high-powered business partners with the national interest. Such relationships like the one between George H. W. Bush and Thomas Devine thus made perfect sense to the CIA.

By the time George H. W. Bush founded his own company, Zapata Petroleum, it was not difficult to line up backers with long-standing ties to industrial espionage activities. The setup with Devine in the oil business provided Bush with a perfect cover to travel abroad and . . . identify potential CIA recruits among foreign nationals.

"Poppy" Bush's own role with intelligence appears to date back as early as the Second World War, when he joined the Navy at age eighteen. On arrival at his training base in Norfolk, Virginia, in the fall of 1942, Bush was trained not only as a pilot of a torpedo bomber but also as a photographic officer, responsible for crucial, highly sensitive aerial surveillance.

After mastering the technique of operating the handheld K-20 aerial camera and film processing, Bush recruited and trained other pilots and crewmen. His own flight team became part bomber unit, part spy unit. The information they obtained about the Japanese navy, as well as crucial intelligence on Japanese land-based defenses, was forwarded to the U.S. Navy's intelligence center at Pearl Harbor and to the Marine Corps for use in planning amphibious landings in order to reduce casualties.

The so-called Operation Snapshot was so hush-hush that, under naval regulations in effect at the time, even revealing its name would lead to court-martial. According to a book by Robert Stinnett, a fellow flier, Admiral Marc Mitscher hit the "bulkhead" when he saw that Bush's team had filed a report in which they actually referred by name to their top-secret project. The three people above Bush in his command chain were made to take razor blades to the pages of the report and remove the forbidden language.

The lesson was apparently not lost on Bush. From that moment forward, as every Bush researcher has learned, Bush's life would honor the principle: no names, no paper trail, no fingerprints. If you wanted to know what Bush had done, you had to have the patience of a sleuth yourself.

Part 2, Skulls and Bones Forever

Sep 25, 2013

(The excerpts in Part 2 come from Chapter 3 of the book, and the titles and subtitles have been changed for this publication.)

Skull and Bones

In 1945, with the end of the war, George H. W. "Poppy" Bush entered Yale University. The CIA recruited heavily at all of the Ivy League schools in those days, with the New Haven campus the standout. "Yale has always been the agency's biggest feeder," recalled CIA officer Osborne Day (class of'43), "In my Yale class alone there were thirty-five guys in the agency." Bush's father, Prescott, was on the university's board, and the school was crawling with faculty serving as recruiters for the intelligence services . . . Yale's society's boys were the cream of the crop, and could keep secrets to boot. And no secret society was more suited to the spy establishment than Skull and Bones, for which Poppy Bush, like his father, was tapped in his junior year. Established in 1832, Skull and Bones is the oldest secret society at Yale, and thus at least theoretically entrusted its membership with a more comprehensive body of secrets than any other campus group. Bones alumni would appear throughout the public and private history of both wartime and peacetime intelligence . . .

When Bush entered Yale, the university was welcoming back countless veterans of the OSS to its faculty. Bush, with naval intelligence work already under his belt by the time he arrived at Yale, would have been seen as a particularly prime candidate for recruitment.

Bonesmen Have All the Muscle

Out of Yale, Bush went directly into the employ of Dresser Industries, a peculiar, family-connected firm providing essential services to the oil industry. Dresser has never received the scrutiny it deserves. Between the lines of its official story can be discerned an alternate version that could suggest a corporate double life.

The S. R. Dresser Manufacturing Company had been a small, solid, unexceptional outfit, . . . [when it found] eager buyers in Prescott Bush's Yale friends Roland and W. Averell Harriman - the sons of railroad tycoon E. H. Harriman - who had only recently set up a merchant bank to assist wealthy families in such endeavors. At the time, Dresser's principal assets consisted of two very valuable patents in the rapidly expanding oil industry. One was for a packer that made it much easier to remove oil from the ground; the other was for a coupler that made long-range natural gas pipelines feasible. Instead of controlling the oil, Dresser's strategy was to control the technology that made drilling possible. W.A. Harriman and Company, which had brought Prescott Bush aboard two years earlier, purchased Dresser in 1928.

Prescott Bush and his partners installed an old friend, H. Neil Mallon, at the helm. Mallon's primary credential was that he was "one of them." Like Prescott Bush, Mallon was from Ohio, and his family seems both to have known the Bushes and to have had its own set of powerful connections. He was Yale, and he was Skull and Bones, so he could be trusted.

Hiring decisions by the Bonesmen at the Harriman firm were presented as jolly and distinctly informal, with club and family being prime qualifications . . . Under Mallon, the company underwent an astonishing transformation. As World War II approached, Dresser began expanding, gobbling up one militarily strategic manufacturer after another. While Dresser was still engaged in the mundane manufacture of drill bits, drilling mud, and other products useful to the oil industry, it was also moving closer to the heart of the rapidly growing military-industrial sector as a defense contractor and subcontractor. It also assembled a board that would epitomize the cozy relationships between titans of industry, finance, media, government, military, and intelligence - and the revolving door between those sectors.

Poppy Gets his Hands Oily

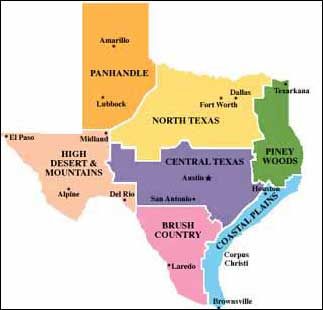

After graduating from Yale in 1948, Poppy headed out to visit "Uncle Neil" at Dresser headquarters, which were then in Cleveland. Mallon dispatched the inexperienced Yale grad and Navy vet, with his wife Barbara and firstborn George W. in tow, to Odessa, the remote West Texas boomtown that, with neighboring Midland, was rapidly becoming the center of the oil extraction business.

Oil was certainly a strategic business. A resource required in abundance to fuel the modern navy, army, and air force, oil had driven the engine of World War II. With the end of hostilities, America still had plenty of petroleum, but the demands of the war had exhausted many oil fields. As President Roosevelt's secretary of the interior and later his petroleum administrator for war, Harold Ickes had warned in 1943, "If there should be a World War III it would have to be fought with someone else's petroleum, because the United States wouldn't have it." Ickes's eye was then on Saudi Arabia.

If the young George H.W. Bush understood anything about the larger game and his expected role in it, he and his wife Barbara certainly did not let on to the neighbors in those early days in dusty West Texas . . . Poppy's initial jobs included sweeping out warehouses and painting machinery used for oil drilling, but he was soon asked to handle more challenging tasks . . .

Dresser was well-known in the right circles as providing handy cover to CIA operatives . . . Continuing his whirlwind "training," Dresser transferred Bush to California, where the company had begun acquiring subsidiaries in 1940. Poppy has never written or spoken publicly in any depth about the California period of his career. He has made only brief references to work on the assembly line at Dresser's Pacific Pump Works in the Los Angeles suburb of Huntington Park and sales chores for other companies owned by Dresser. In later years, when criticized for his anti-union stands, he would pull out a union card which he claimed came from his membership in the United Steelworkers Union. Why Bush joined the Steelworkers (and attended their meetings) is something of a mystery, since that union was not operating inside Pacific Pump Works.

To be sure, the company was not just pumping water out of the ground anymore. During World War II, Pacific Pump became, like Dresser, an important cog in the war machine. The firm supplied hydraulic-actuating assemblies for airplane landing gear, wing flaps, and bomb doors, and even provided crucial parts for the top-secret process that produced the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

While in California training for Dresser, Poppy, the pregnant Barbara, and little George W. were constantly on the go, with at least five residences in a period of nine months - Huntington Park, Bakersfield, Whittier, Ventura, and Compton. Poppy was often absent, according to Barbara, even from their brief-tenure outposts. Was he truly a Willy Loman, peddling drill bits, dragging a pregnant wife and a one-year-old child with him? Or was he doing something else? Although "ordinary" scions often toil briefly at the bottom, Bush was no ordinary scion.

Bush would so effectively obscure his life that even some of his best friends seemed to know little about what he was actually doing - though they may have intuited it. A longtime friend of Bush's said that Bush probably would have been happiest as a career intelligence officer. Another longtime Bush associate told a reporter anonymously that Poppy's own accounts of various periods in his life "are often off 10 to 30 percent ... there is a certain reserve, even secretiveness."

From Dallas, with Love

In 1950, during the time Poppy Bush squired a Yugoslav Communist around the oil fields for Dresser Industries, the cold war got hot in an unexpected quarter when North Korean Communist forces launched an invasion of the south. Their attack had not been even vaguely anticipated in the National Intelligence Estimate - from the fledgling CIA - which had arrived on the president's desk just six days before. Heads rolled, and in the ensuing shake-up, Allen Dulles became deputy director in charge of clandestine operations, which included both spying and proactive covert operations. For the Bushes, who had a decades-long personal and business relationship to the Dulles family, this was certainly an interesting development.

The Dulles and Bush clans had long mixed over business, politics, and friendship, and the corollary to all three - intelligence. Even as far back as World War I, while Dulles's uncle served as secretary of state, Prescott's father, Samuel Bush, oversaw small arms manufacturing for the War Industries Board, and young Allen played a crucial role in the fledgling intelligence services operations in Europe. Later, the families interacted regularly as the Bush clan plied their trade in investment banking and the Dulleses in the law.

In 1950, Dresser was completing a corporate relocation to Dallas which, besides being an oil capital, was rapidly becoming a center of the defense industry and its military-industrial-energy elite. Though a virtual unknown on his arrival, Neil Mallon quickly set about bringing the conservative titans of Dallas society together in a new local chapter of the non-profit Council on World Affairs, in whose Cleveland branch he had been active. Started in 1918, the World Affairs Councils of America were a localized equivalent of the Rockefeller-backed Council on Foreign Relations, the presidency of which Allen Dulles had just resigned to take his post at the CIA.

A September 1951 organizing meeting at Mallon's home featured a group with suggestive connections and affiliations. It included Fred Florence, the founder of the Republic National Bank, whose Dallas office tower was a covert repository for CIA-connected ventures; T. E. Braniff, a pioneer of the airline industry and member of the Knights of Malta, an exclusive, conservative, Vatican-connected order with longtime intelligence ties; Fred Wooten, an official of the First National Bank of Dallas, which would employ Poppy Bush in the years between his tenure as CIA director and vice president; and Colonel Robert G. Storey, later named as liaison between Texas law enforcement and the Warren Commission investigating the assassination of President Kennedy.

Soon the group moved even closer to the center of power. General Dwight Eisenhower . . . had responded to entreaties from a GOP group that included the Rockefellers and Prescott Bush, as well as Allen and John Foster Dulles....With Ike the Republican nominee, they all scrambled for seats on his train. The Dulleses were key advisers. Prescott Bush was backing Ike and mounting what would be a successful race for a Senate seat from Connecticut. Prescott's son George H. W. Bush was not left out. He became the Midland County chairman of the Eisenhower-Nixon campaigns in both 1952 and 1956. With the West Texas city at the center of the oil boom, young George functioned as a crucial link between the Eastern Establishment, the next Republican administration, and Midland's oil-based new wealth.

Following Ike's decisive victory, the Dulles brothers obtained effective control of foreign policy: John Foster became Ike's secretary of state, and Allen the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. The rest of the administration was filled with Bush allies, including national security adviser Gordon Gray, a close friend of Prescott's, and Treasury Secretary Robert B. Anderson, a sometime member of the Dresser Industries board.

Eisenhower, with no track record in civilian government and little enthusiasm for the daily grind, was only too happy to leave many of the operational decisions to these others . . . Some of those businessmen taking it upon themselves to help chart the course were from the Dallas group. Shortly after Ike took office, Mallon's Council of World Affairs announced its intention to send fifteen members on a three-month world tour, for meetings with what the group characterized as "responsible" political and business leaders. Shortly after the group returned, Dulles came to visit with the Dallas council chapter . . .

At the time, the CIA was in the process of creating plausible liability as it began what would be a series of efforts to topple "unfriendly" regimes around the world, including those in Guatemala and Iran. Since the CIA's charter severely constrained the domestic side of covert operations, agents created a host of entities to serve as middlemen to support rebels in countries targeted for regime change. During the early days of Dresser in Dallas - and of Zapata Petroleum - Dulles was just beginning to experiment with "off the books" operations. Eventually, by the seventies and eighties, when Poppy Bush ran the CIA and coordinated covert operations as vice president, hundreds, perhaps thousands, of such entities had been created.

The Bones of Zapata Petroleum

In 1953, as Dulles was building his global machine, Poppy Bush launched his own enterprise, with help from Dulles, Mallon, and Poppy's maternal uncle Herbert Walker.

Bush got money from Uncle Herbie (George Herbert Walker Jr., Skull and Bones, 1927), an investment banker. Uncle Herbie also was instrumental in bringing in others, including Eugene Meyer, a Yale graduate and owner of the influential Washington Post. Meyer was one of many media titans, such as Prescott's good friend and fellow Bonesman Henry Luce, founder of Time magazine, and William Paley of CBS (on whose board Prescott sat), who shared an interest in intelligence. In a 1977 Rolling Stone article, Carl Bernstein, famed for breaking the Watergate story in the Washington Post, states that both Luce and Paley cooperated regularly with the CIA, and even mentions his own paper's history with the agency, though he does not fully probe the Post's intelligence connections.

The news business, the policy business, and the intelligence business had a lot in common: they were all about whom you knew and what you knew. In fact, so was the oil business. The Bushes' skill at cultivating connections was evident in 1953, when Poppy joined forces with a couple of brothers, Hugh and Bill Liedtke, to form Zapata Petroleum. Based on a "hunch" of Hugh Liedtke's, the company drilled 127 consecutive "wet" holes, and the firm's stock exploded from seven cents a share to twenty-three dollars a share.

Pirates of the Caribbean

... Mallon would play a crucial role for Dulles by introducing him to the powerful new-moneyed oil elites in Dallas that would, along with a separate group in Houston, become the leading funders of off-the-books covert operations in Latin America. They would commence with efforts to overthrow Latin American and Caribbean leaders in the 1950s. The efforts would continue, under Poppy Bush, with Iran-contra in the 1980s.

Zapata Offshore . . . [was] launched by Poppy in 1954, just as the U.S. government, under an administration dominated by the Dulles-Bush circles, began auctioning offshore mineral rights.

In 1958, Zapata Offshore's drilling rig Scorpion was moved from the Gulf of Mexico to Cay Sal Bank, the most remote group of islands in the Bahamas and just fifty-four miles north of Isabela, Cuba. The [Cay Sal] island had been recently leased to oilman Howard Hughes, who had his own long-standing CIA ties, as well as his own "private CIA."

By most appearances, a number of CIA-connected entities were involved in the operation. Zapata leased the Scorpion to Standard Oil of California and to Gulf Oil. CIA director Dulles had previously served as Gulf's counsel for Latin America. The same year that Gulf leased Bush's platform, CIA veteran Kermit "Kim" Roosevelt joined Gulf's board. This was the same Kermit Roosevelt who had overseen the CIA's successful 1953 coup against the democratically elected Iranian prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, after Mossadegh began nationalizing Anglo-American oil concessions. It looked like the Bush-CIA group was preparing for operations in the Caribbean basin.

The offshore platforms had a specific purpose. "George Bush would be given a list of names of Cuban oil workers we would want placed in jobs," said one official connected to Operation Mongoose, the program to overthrow Castro. "The oil platforms he dealt in were perfect for training the Cubans in raids on their homeland."

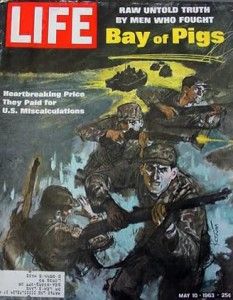

The importance of this early Bush connection with Cuba should not be ignored in assessing his connections to contemporaneous events. For example, it sheds light on the 1963 memo from J. Edgar Hoover discovered by reporter Joseph McBride. The memo, which mentioned a briefing about Cuban activity in the wake of the JFK assassination, had been given to "George Bush of the CIA." Years later, many figures from the Bay of Pigs operation would resurface in key positions in administrations in which Poppy Bush held high posts, and during his presidency. Others would show up in off-the-books operations run by Poppy's friends and associates.

George H. W. Bush did not, however, limit himself to the Caribbean. This period of his life was characterized by frenetic travel to all corners of the world, though Zapata had only a handful of rigs. The pattern would continue through his entire career. He set up operations for Zapata Offshore in the Gulf of Mexico, the Persian Gulf, Trinidad, Borneo, and Medellín, Colombia. Clients included the Kuwait Shell Petroleum Development Company, which began his close association with the Kuwaiti elite.

Facing Fidel

That a lot of what was labeled "national security" work was largely about money - making it, protecting it - was fairly transparent. Through the story of the Bushes and their circle runs a thread of entitlement to resources in other countries, and anger and disbelief when others challenged that claim.

Upon coming to power in 1959, Fidel Castro began to expropriate the massive properties of large foreign (chiefly American) companies. The impact fell heavily on American corporations that had massive agricultural and mineral operations on the fertile island, including Brown Brothers Harriman, whose extensive holdings included the two-hundred-thousand-acre Punta Alegre beet sugar plantation. After Castro took power, the Eisenhower administration began a boycott of Cuban sugar, which is a crucial component of the island's economy. The Cubans in turn became increasingly dependent on the USSR as supplier of goods and protector.

Poppy swung into gear the same year that Castro began nationalizing [American] properties. He severed his ties to the Liedtkes by buying out their stake in Zapata Offshore, and then moved its operations to Houston - which, unlike the remote Midland-Odessa area, had access to the Caribbean through the Houston Ship Channel. Meanwhile, back in Washington, after extensive planning, the Bay of Pigs project began with Eisenhower's approval on March 17, 1960.

Beyond providing a staging area for Cuban rebels, Zapata Offshore appears to have served as a paymaster. "We had to pay off politicians in Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and elsewhere," said John Sherwood, chief of CIA anti-Castro operations in the early 1960s. "Bush's company was used as a conduit for these funds under the guise of oil business contracts . . . The major breakthrough was when we were able, through Bush, to place people in PEMEX - the big Mexican national oil operation."

Zapata filings "inadvertently destroyed"

The complicated PEMEX affair began in 1960, when Zapata Offshore offered a lucrative secret partnership to a competing Mexican drilling equipment company, Perforaciones Marinas del Golfe, or Permargo. George H. W. Bush did not want this relationship exposed, even decades later. When investigative reporter Jonathan Kwitny tried to document Bush's precise involvement with Permargo for a 1988 article, he was told by an SEC spokeswoman that Zapata filings from 1960 to 1966 had been "inadvertently destroyed" several months after Bush became vice president.

Evidence that Zapata Offshore was more than just Poppy Bush's oil company surfaced in the years that followed. Bush increasingly spent his time on politics, and others were brought in to transform the company into a larger entity that could more credibly run global operations . . . Bush's reward for all his troubles may have come in 1965, when one of the company's rigs was ostensibly lost in Hurricane Betsy. For the first time in its history, the insurance giant Lloyds of London paid out an oil-platform disaster claim without physical evidence. Zapata received eight million dollars for a rig that had cost only three million. The fate of the rig remains a mystery. Poppy's brother Bucky recalled the fears expressed by Zapata offshore staff that it would be impossible for an insurance claim to be paid because of the absence of any wreckage. But Poppy himself was calm, reassuring his people that "everything was going to be all right."

The financials of Zapata, like those of latter-day Enron, were almost impossible to understand. This appears to have been by design. A bit of this can be gleaned from the words of the company's former executive Bob Gow, another in a small army of Bush loyalists who show up repeatedly in the family story - and by extension the nation's.

What Was Zapata?

Bob Gow may be the only person in American history to be employed by one future president (Poppy Bush - at Zapata) and to later employ another (George W. - at Gow's post-Zapata agricultural mini-conglomerate Stratford of Texas).

In 2006, I traveled to Mexico, to the western Yucatan, and met with Gow... I also obtained Gow's self-published memoirs, the five hundred pages of which include much about Zapata, bamboo, beeswax, and catfish, but manage to say little about the Bushes and their doings. Gow did, however admit that he did some spying for the CIA.

Gow was a member of the country's mostly invisible elites.

Bob Gow and Ray Walker [cousin of George H.W. Bush] would room together again at Yale, and both would be inducted into the 1955 class of Skull and Bones.

Gow's recruitment by the Bushes illustrates the kind of opportunities that come to those of the "right sort" and possessed of the appropriate discretion.

Gow portrays Bush as traveling constantly when he was Zapata chief, and far from connected when on premises . . . Though Gow has little to say in his book about the company's underlying operations or Poppy's role in them, he proudly notes Zapata's complex web of foreign ventures. In all probability, the foreign operations had dual functions. Since Zapata was set up with guidance from Neil Mallon, it is likely that the overseas undertakings were modeled in part on Dresser's. According to the in-house history of Dresser, one of the company's bolder moves was a then-innovative tax strategy that involved a separate company in the tiny European principality of Liechtenstein. "A considerable [benefit] was the fact that no American taxes had to be paid on international earnings until the money was returned to the United States." That is, if the money was ever returned to the United States. And there was another characteristic of funds that were not repatriated: they were out of sight of federal authorities. There was no effective way to know where they went ultimately, or for what purposes.

That was Dresser. Now, Zapata, according to Gow:

Zapata, at that time, consisted of a number of foreign corporations incorporated in each county where our rigs operated . . . It was largely the brainchild of the tax department at Arthur Andersen and the tax lawyers at Baker and Botts . . . Until the profits were brought back to the United States, it was not necessary at that time to pay U.S. taxes on them. Because of the way Zapata operated around the world, it seemed as though it never would be necessary to pay taxes . . . As time passed and Zapata worked in many other countries, Zapata's cash . . . was in the accounts of a large number (dozens and dozens) of companies located in almost all the countries around the world where Zapata had ever drilled.Whether Zapata was partially designed for laundering money for covert or clandestine operations may never be known. But one thing is certain: spy work depends, as much as anything, on a large flow of funds for keeping foreign palms greased. It is an enormously expensive business, and it requires layers and layers of ostensibly unconnected cutouts for the millions to flow properly and without detection.

So what, exactly, was Zapata? Was it CIA? Gow won't say. Although in his memoirs he freely admits that he served the CIA later on, he strives mightily to avoid extensive discussion of the Bush clan.

Then I asked Gow about allegations that Zapata Offshore had played a role in the Bay of Pigs invasion: "Any comments on those?"

Gow hesitated a moment, smiled just a bit, and then replied, "No."

Part 3: Where was Poppy November 22, 1963?

Oct 2, 2013

(The excerpts in Part 3 come from Chapter 4 of the book, and the titles and subtitles have been changed for this publication.)

"Somewhere in Texas"

George H. W. Bush may be one of the few Americans of his generation who cannot recall exactly where he was when John F. Kennedy was shot in Dallas on November 22, 1963.

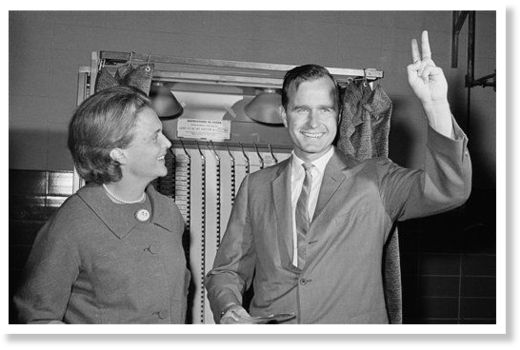

At times he has said that he was "somewhere in Texas." Bush was indeed "somewhere" in Texas. And he had every reason to remember. At the time Bush was the thirty-nine-year-old chairman of the Harris County (Houston) Republican Party and an outspoken critic of the president. He was also actively campaigning for a seat in the U.S. Senate at exactly the time Kennedy was assassinated right in Bush's own state. The story behind Bush's apparent evasiveness is complicated. Yet it is crucial to an understanding not just of the Bush family, but also of a tragic chapter in the nation's history.

Who Wanted Kennedy Dead?

The two and a half years leading up to November 22, 1963, had been tumultuous ones. The Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961, designed to dislodge Fidel Castro and his Cuban revolution from its headquarters ninety miles off the Florida Keys, was an embarrassing foreign policy failure. Certainly in terms of lives lost and men captured, it was also a human disaster. But within the ruling American elite it was seen primarily as a jolt to the old boys' network - a humiliating debacle, and a rebuke of the supposedly infallible CIA. For John Kennedy it also presented an opportunity. He had been impressed with the CIA at first, and depended on its counterinsurgency against Communists and nationalists in the third world. But the Bay of Pigs disaster gave him pause. Whatever Kennedy's own role in the invasion fiasco, it had been planned on Dwight Eisenhower's watch. Kennedy had been asked to green-light it shortly after taking office, and in retrospect he felt the agency had deceived him in several key respects.

The most critical involved Cubans' true feelings toward Castro. The CIA had predicted that the island population would rise up to support the invaders. When this did not happen, the agency, Air Force, Army, and Navy all put pressure on the young president to authorize the open use of U.S. armed forces. In effect they wanted to turn a supposed effort of armed Cuban "exiles" to reclaim their homeland into a full-fledged U.S. invasion. But Kennedy would not go along. The success of the operation had been predicated on something - a popular uprising - that hadn't happened, and Kennedy concluded it would be foolish to get in deeper.

Following the disaster, CIA director Allen Dulles mounted a counteroffensive against criticism of the agency. Dulles denied that the plan had been dependent on a popular insurrection. Just weeks after the calamity, he offered this account on Meet the Press: "I wouldn't say we expected a popular uprising. We were expecting something else to happen in Cuba . . . something that didn't materialize." For his part Kennedy was furious at Dulles for this self-serving explanation. He also was deeply frustrated about the CIA's poor intelligence and suspected that the CIA had sought to force him into an invasion from the very beginning.

The president told his advisers he wanted "to splinter the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter it to the winds." Within weeks of the invasion disaster, Washington was speculating on Dulles's departure. By autumn, he was gone, along with his lieutenants Charles Cabell and Richard Bissell. But in the end, it was not the CIA but rather John F. Kennedy who was destroyed.

The assassination of JFK has fathered a thousand theories, and nearly as many books and studies. Through it all, no consensus has emerged. Most "respectable" academics, journalists, and news organizations don't want to get near the matter, lest they be labeled conspiracy nuts. Most Americans harbor an overwhelming psychic resistance to what retired UC Berkeley professor and author Peter Dale Scott has called the "deep politics" surrounding the assassination. Few of us care to contemplate the awful prospect that the forces we depend upon for security and order could themselves be subverted.

When the Kennedy assassination is mentioned, the inquiry tends to focus on the almost impossible task of determining who fired how many shots and from where. This obsession with the gun or guns bypasses the more basic - and therefore more dangerous questions: Who wanted Kennedy dead, and why? And what did they hope to gain?

Earl Warren to LBJ: "I'll just do whatever you say."

The years since the first assassination investigation was hastily concluded in September 1964 have not been kind to the Warren Commission. Subsequent inquiries have found the commission's process, and the resulting report, horrendously flawed. And there are lingering questions about the very origins of the commission. First, all the members were appointed by Kennedy's successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, who was - stark as this may sound - a chief beneficiary of the assassination, having immediately replaced the dead president to become the thirty-sixth president of the United States.

The commission's chairman was the presiding chief justice of the Supreme Court. Earl Warren was the perfect choice because he was seen by the public as an honest, incorruptible man of substance. Warren's involvement gave the commission a certain credibility and convinced major newspapers like the New York Times to continue supporting the commission report over the years.

Warren resisted LBJ's call to service, but finally acquiesced, leading the panel to the conclusions it reached. To get Warren to say yes, Johnson had warned the justice that Oswald might be tied, through an alleged Mexico City visit, to the Soviets and Cubans. He implied that this could lead to nuclear war if level heads did not prevail.

As Johnson explained in a taped telephone conversation with Senator Richard Russell, himself reluctant to join the panel:

Warren told me he wouldn't do it under any circumstances . . . He came down here and told me no - twice. And I just pulled out what [FBI director] Hoover told me about a little incident in Mexico City . . . And he started crying and he said, "I won't turn you down. I'll just do whatever you say."And that got Warren - and the public trust he brought - on board.

Allen Dulles, the member who asked the most questions, would have been himself considered a prime suspect by any standard police methodology. Moreover, he was expert not only in assassinations but also in deception and camouflage.

Dulles's animus toward Kennedy was never overt, but it was incontrovertible. In ousting him, Kennedy was showing the door to a man who had spent his entire adult life in spy work. Behind the pipe-smoking, professorial mien, Allen Dulles was a ruthless, calculating man with blood on his hands. Certainly, the veteran master spy, director since 1953, could not have expected to stay on under Kennedy indefinitely. But to be forced out after what seemed to him a glorious decade of covert operations (including successful coups in Guatemala and Iran) - and on account of what he considered Kennedy's failure of nerve regarding the Bay of Pigs invasion - must have been galling. Dulles was, according to his subordinate E. Howard Hunt, a "remarkable man whose long career of government service had been destroyed unjustly by men who were laboring unceasingly to preserve their own public images."

"I have never forgiven them."

Among those infuriated with the Kennedys was none other than Dulles's good friend Senator Prescott Bush. In 1961, when Dulles brought his successor, John McCone, to a dinner at Prescott's home, the senator recalled that he "tried to make a pleasant evening of it, but I was sick at heart, and angry too, for it was the Kennedy's [sic] that brot [sic] about the [Bay of Pigs] fiasco."

He expressed this anger in a condolence letter to Allen Dulles's widow in 1969, discovered among Dulles's papers at Princeton University. Prescott's next line is particularly memorable: "I have never forgiven them." The expression of such lingering resentment, six years after JFK's death, was doubly chilling because it came just months after a second Kennedy, Robert, had been gunned down under mysterious circumstances, once again by a seemingly unstable lone gunman.

Clearing the Way for Poppy

In the spring of 1962, about six months after Dulles's departure from the Kennedy administration, both Prescott Bush and his son Poppy made some considerable and rather abrupt changes to their lives. Prescott Bush, having already begun his reelection campaign and opened his headquarters, surprised virtually everyone by reversing himself and announcing that he would not seek a new term after all. The reason he gave was that he was tired and physically not well enough to endure another six years. This decision struck people as curious, in part because Prescott so dearly loved his life in Washington, and in part because he would turn out to be physically robust for a number of years afterward, and would even express his deep regret at having chosen to leave the Senate. Whatever took him away from Washington seems to have been pressing.

Just as Prescott was leaving the political arena, his son was entering it at high speed. Poppy, who until then had been barely involved with local Houston politics, suddenly became consumed with them. Conventional accounts treat Bush's new interest as simply the next step in the life of an ambitious man, but for the Bush family, there was an almost inexplicable urgency. At a Washington political gathering, Prescott pulled aside the Harris County (Houston) GOP chairman, James Bertron, and demanded that Bertron find a place in his organization for Poppy. "Senator," replied Bertron, "I'm trying. We're all trying."

This pressure quickly paid off. In the fall of 1962, Poppy was named finance co-chair of the Harris County Republican Party, a position which likely entailed visiting wealthy oilmen and asking them for money. Just a few months later, in early 1963, James Bertron abruptly announced his intention to retire and move to Florida, and Poppy announced his intention to succeed him. A party activist who had expressed his desire for the position suddenly abandoned his candidacy, and Bush won the position by acclamation. Now he had a plausible reason not only to be visiting with wealthy oilmen, but also to be building an operational team, ostensibly for political purposes.

Oiling the Rest of the Way for Poppy

That summer of 1963, right in the middle of his move out of the oil business into politics, Poppy Bush embarked on a busy itinerary of foreign business travel for Zapata Offshore. The trip seemed ambitious, especially when one considers the realistic opportunities for a firm with just a few rigs.

Upon his return, Poppy's new lust for political power hit warp speed: now he had decided to seek a U.S. Senate seat. In less than a year he had gone from uninvolved to finance co-chair to county chairman to U.S. Senate hopeful. As a businessman engaged in offshore drilling, Poppy Bush had little reason to be traveling extensively throughout Texas. As Harris County chairman, Poppy had Houston as his bailiwick. But as a Senate candidate, he had every reason to be seen all over the Lone Star State.

Bush's political work, like his oil work, may have been cover for intelligence activity. But there were political objectives as well, ones that conflicted with those of John Kennedy. In deciding to run for U.S. Senate, Poppy was playing a key role in the Republican effort to unyoke the conservative south from the Democratic wagon it had pulled to victory in 1960. Jack and Bobby Kennedy, meanwhile were busy strategizing exactly how to prevent that - and this was going to be a crucial battle, given JFK's wafer-thin victory in the previous election. Two states in particular would be battlegrounds: Florida and Texas. In theory, a candidate like Poppy Bush, with his family connections to Wall Street, could be a strong fund-raiser and perhaps contribute to a substantially increased Republican turnout in 1964, even if Bush himself was not elected. To head off this larger threat, it was clear to Kennedy's political advisers that Jack would have to campaign in Texas, along with Florida. Kennedy was interested in revoking the oil depletion allowance, a decision that would have meant steep losses for Texas oilmen, and he continued voicing his support for civil rights, always a contentious issue in the South.

As a candidate for statewide office, Poppy Bush was on the go in the fall of 1963, moving around Texas and spending time in Dallas, where he opened a headquarters.

Another Memory Lapse

Jack Kennedy's death in Dallas on November 22, 1963, was one of the most tragically memorable moments in the lives of those who lived through it. So Poppy Bush's inability or unwillingness to say where he was on that day is extremely odd, to say the least.

His haziness became an issue a quarter century after the assassination - when there emerged yet another good reason for Bush to have recalled that day vividly. On Thursday, August 25, 1988, about six weeks after the Nation published Joseph McBride's piece on "George Bush of the CIA" - and just a week after George H. W. Bush accepted the Republican presidential nomination - a short article appeared in the San Francisco Examiner, with the intriguing headline: "Documents: Bush Blew Whistle on Rival in JFK Slaying." The article began like this:A man who identified himself as George H. W. Bush phoned the FBI in Houston a few hours after President John F. Kennedy's assassination in Dallas to report that a right-wing Young Republican had "been talking of killing the president," FBI documents show.

The FBI, the article goes on to say, promptly followed up on Bush's tip and interviewed the Young Republican, a man by the name of James Milton Parrott. Parrott claimed he had never threatened Kennedy, and his mother declared that he had been at home with her in Houston all day.

The author of this story, the Examiner's Miguel Acoca, had been unable to reach Parrott but noted that the FBI report on Bush's call listed the address of the tipster as 5525 Briar, Houston, Texas - the address of the man who was now, in 1988, vice president of the United States.

Like Bush, Acoca, a Panamanian, had graduated from Yale. He spent the early 1960's in the Miami area working for Life magazine, where dinners at his Coconut Grove apartment were typically populated by Cuban émigrés and CIA officers managing the war against Castro. While still in Miami, Acoca became interested in the group running the CIA's JM/WAVE Cuban operations station in the area, and developed a growing obsession with assassinations in general, and JFK's in particular.

Acoca had placed a call to Bush's office once he discovered that the vice president had been the tipster back on November 22, 1963. His call brought a familiar response:

Bush's press office at first said the vice president hadn't made the call and challenged the authenticity of the FBI reports. Then, several days later, an aide said Bush "does not recall" making the call.Acoca's story about Bush didn't get much attention, running on page A-II of the Examiner. The media reaction was similar to that which greeted journalist Joseph McBride's earlier revelations: next to nothing. A few newspapers picked up the Examiner piece off the Hearst wire, but not a single paper bothered to assign reporters to follow up.

Thus, neither of two vexing questions - whether George Bush had been a CIA operative in 1963, and whether he had called the FBI on November 22 with purported information related to the JFK assassination - became issues for Bush in 1988 as he sailed into the White House.

By the fall of 1992, though, things were growing uncomfortable for President Bush. Arkansas governor Bill Clinton's challenge was gaining momentum, the economy was in the doldrums, and now an initiative from Congress and the public posed a new dilemma for Poppy. Oliver Stone's JFK, released in December 1991, had aroused public interest and helped prod Congress to unanimously pass the President John F. Kennedy's Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992. It required each federal agency to collect and forward all records about the JFK assassination to the National Archives, which would then make them available to the American people.

The 1988 Acoca article that caused so little stir had been based on a brief FBI summary of Bush's tip about Parrott. But there was a longer, more detailed memo in the archives, waiting to be unearthed and released.

President George H. W. Bush now found himself in the awkward position of potentially outing himself. Should he veto the politically popular JFK Act just days before voters would go to the polls to choose between him and his surging challenger, Bill Clinton? Bush, with little enthusiasm, signed the bill - though, in a move that his son George W. Bush would use without restraint, Poppy issued a "signing statement" that essentially attached conditions, asserting unilateral executive authority to withhold records on the basis of several concerns, including national security. Still, Poppy couldn't claim national security about everything, certainly not about documents that some already knew to exist, especially documents that had his own name on them.

Whether he knew it or not, with his signature, Poppy was moving the more detailed "Parrott memo" toward the light of day. In fact, government records show that the complete FBI memo from December 22, 1963, laying out the particulars of Bush's call to the agency was finally declassified in 1993, along with thousands of other papers - by the Clinton administration.

Wrong Tip at the Wrong Time

That memo, reporting the call that had come in on the day of the assassination to Special Agent Graham W. Kitchel of the Houston FBI bureau, contained some important new identifying information and other details:

[DATE: November 22, 1963]The memo contained several intriguing details, but no news organization picked up on them. Indeed, no one paid any heed to the whereabouts of Poppy Bush at the time of the JFK assassination - except Barbara Bush. In 1994, three decades after Poppy began not remembering where he was on November 22, 1963, it was suddenly Barbara who remembered.

At 1:45 p.m. Mr. GEORGE H.W. BUSH, President of the Zapata Off-shore Drilling Company, Houston, Texas, residence 5525 Briar, Houston, telephonically furnished the following information to writer by long distance telephone call from Tyler, Texas.

BUSH stated that he wanted to be kept confidential but wanted to furnish hearsay that he recalled hearing in recent weeks, the day and source unknown. He stated that one JAMES PARROTT has been talking of killing the president when he comes to Houston.

BUSH stated that PARROTT is possibly a student at the University of Houston and is active in political matters in this area. He stated that he felt MRS FAWLEY, telephone number SU 2-5239, or ARLENE SMITH, telephone number JA 9-9194 of the Harris County Republican Headquarters would be able to furnish additional information regarding the identity of PARROTT.

BUSH stated that he was proceeding to Dallas, Texas, would remain in the Sheraton-Dallas Hotel and return to his residence on 11-23-63. His office telephone Number is CA 2-0395.

To be continued.....

. . . all the way to the bottom here it has perhaps become apparent that the G. H. W. Shrub is amoung the truly tedious toads on the BBM.

And not that the Middle Shrub's sorry sojourns are by any means unique, but along with Webster Tarpley's," Geo. Bush - The Unauthorized Biography," Baker's book promises to be an absolutely soul-grinding exercise to read.

That said it really is required reading for anyone's course in "Self-disabuse of Belief in the Goodness of Government - 101."

Graduate courses are available . . . if one can handle them.