OF THE

TIMES

"We have about 50% of the world's wealth but only 6.3% of its population. This disparity is particularly great as between ourselves and the peoples of Asia. In this situation, we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment. Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity without positive detriment to our national security. To do so, we will have to dispense with all sentimentality and day-dreaming; and our attention will have to be concentrated everywhere on our immediate national objectives. We need not deceive ourselves that we can afford today the luxury of altruism and world-benefaction."

~ US State Department, 1948

" Que la malédiction d'Allah soit sur les injustes,» (Coran 7/44) ».

What the early humans did was to adapt culture to exploit the environment. That is, using the brain, not the body, to evolve. This leads to much...

" Que la malédiction d'Allah soit sur les injustes,» (Coran 7/44) ».

Didn't we all say nothing would be done? No surprise.

"Western tycoon claims Zelensky associates trying to extort millions of euros" This should read: Western tycoon claims Zelensky associates trying...

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

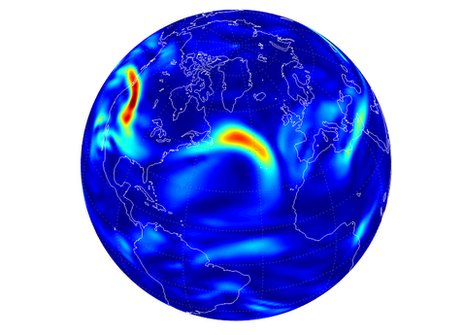

If increase in approaching comets increases the size and number of Turbulence Zones on Earth this increases the distances planes have to travel around increasing their fuel usage and increasing price of tickets.

We may arrive to a point when turbulence zones become so violent that they make flight unsafe and flight paths around these dangerous too long, requiring too much fuel resulting in overall unsupportable air-travel situation, effectively downing all/most flights. Only in cases of extreme necessity flights will be risked..

Increasing wind strength makes unruly seas increasing storms strength at sea making travel by sea equally an unusually risky business.

We might arrive to a new meaning of GROUNDED.