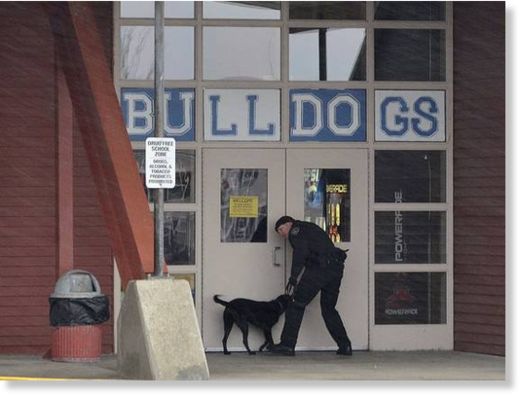

- Students in Los Angeles this week saw the first patrols by uniformed officers, newly assigned to every school.

- In Newtown, Conn., a few parents say the sight of uniformed officers is a comfort to children. Superintendent Janet Robinson has said she wants the police presence to continue.

But a few advocates for children aren't sold on the idea.

The Advancement Project, a Washington, D.C.-based civil rights group, has long complained that armed officers in schools actually make safety worse for many kids, making it more likely that they'll end up in trouble with the law. The group on Friday will propose that schools develop long-term safety plans and invest funding that would otherwise go to more police into conflict resolution and better access to mental health services for students.

"No more money should be thrown at police," Advancement Project co-Director Judith Browne-Dianis said.

The group tracked school referrals to Florida's juvenile justice system in 2010-11 and found that of 16,400 referrals, 69% were for misdemeanors. "Students aren't being arrested in school for safety concerns," Browne-Dianis said. "Those referrals are for things like disorderly conduct."

Police posted to schools are rarely called upon to protect students from outside attacks, she said. Police become the de facto disciplinary arm of the school, Browne-Dianis said. In many cases they end up having a detrimental impact "on young people that they were intended to protect."

The group's position on more cops in schools is actually backed up by the public: Only 41% support a National Rifle Association proposal to put armed officers in schools; 50% oppose it, according to a Public Policy Polling survey released this week.

After the shooting, some school districts around the country asked police departments to increase patrols. "A barrier has been broken in our culture" by the shootings, Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck said last month. "It's our job ... all of our jobs, to make sure that we resurrect that barrier and make our children safe." In Los Angeles, officers will rotate daily through each of the city's 600-plus schools.

Many districts are revisiting safety plans and looking at issues such as whether school resource officers traditionally at middle and high schools should be deployed to elementary schools, said Francisco Negron, general counsel for the National School Boards Association.

In a position paper released Wednesday, The American Federation of Teachers said police in schools "should be part of the fabric of the school community, not simply a stationed armed guard."

John Bello, a Newtown, Conn., real estate developer, said his 7-year-old-son, who lost two friends in the shooting at Sandy Hook, has been happy to see the police officers stationed at Head O'Meadow Elementary School since the shooting. "I said, 'Did you see the police?' and he said, 'Yeah, that's good,'" Bello said.

Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy has convened a task force to review state laws and policies affecting guns, mental health and school safety, but during his State of the State address on Wednesday, he told a joint session of the General Assembly, "Freedom is not a handgun on the hip of every teacher, and security should not mean a guard posted outside every classroom."

Browne-Dianis said the Newtown shooting was a tragedy, but that "police are not the answer."

The group hopes to dissuade the White House from proposing more police in schools. "If that becomes the answer, we're going to be in more of a quagmire than we've been in," she said. "Having an armed guard at every school is not going to give us the safety that we need over the long haul."

Contributing: The Associated Press

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter