If a doctor suspects their patient may be diabetic, they can run an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), in which the patient is given a glucose load, and subsequent blood response is measured to see how effectively the glucose is cleared from the blood. In a non-diabetic, the blood sugar only rises a relatively small amount, as the intact and functional beta cells of the pancreas secrete just the right amount of insulin to reduce the blood sugar levels to normal levels.

If a person is given an OGTT and their blood sugar spikes more than expected, then by definition they are glucose intolerant. They have failed their OGTT, and cannot tolerate carbohydrates the way a non-diabetic can.

In medical school, we are taught that the primary goal in treating diabetics is to keep blood sugar levels low, and that hemoglobin A1C levels are predictors of further disease progression. There are two major ways to control this blood glucose level, with what we put into our bodies as well as ways to control the blood glucose after it has already risen, such as insulin or other diabetes drugs, such as the alpha-glucosidase inhibitors.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors are a category of drug that work by decreasing the absorption of carbohydrates in your gut, resulting in a smaller rise in blood glucose. However, the unabsorbed carbohydrates need to go somewhere, causing the predicted unpleasant side effects of stomach discomfort and diarrhea.

Now instead of taking a drug that will reduce our absorption of carbohydrates, result in various side effects and and cost additional money, why not just eat less of the very foods spiking the blood sugar in the first place? In other words, why would the American Diabetes Association tell us that a diabetic diet should be 40-50% of the calories from carbohydrates, when by definition, these are the very foods they cannot tolerate? Here is how they describe it on their meal planning page:

How Much Carb?It seems equivalent to a person with a peanut allergy slightly lowering their peanut intake and just injecting him or herself with an epinephrine pen after each meal. Why not just stop eating peanuts and avoid the potential side effects of epi injections? Why don't they just not eat the carbohydrates in the first place? After all this was the treatment of diabetes in the pre-insulin era. Here is how Dr. Elliot Proctor Joslin described it in 1893:

A place to start is at about 45-60 grams of carbohydrate at a meal. You may need more or less carbohydrate at meals depending on how you manage your diabetes. You and your health care team can figure out the right amount for you. Once you know how much carb to eat at a meal, choose your food and the portion size to match.

Diabetic treatment is of the first importance. The carbohydrates taken in the food are of no use to the body and must be removed by the kidneys thereby entailing polydipsia, polyuria, pruritis and renal disease...The beneficial effects were seen at once, and she was advised to "eat all the cream, butter and fatty foods possible.And here is how the Joslin Diabetes Center, named after Dr. Joslin above, describes it 120 years later:

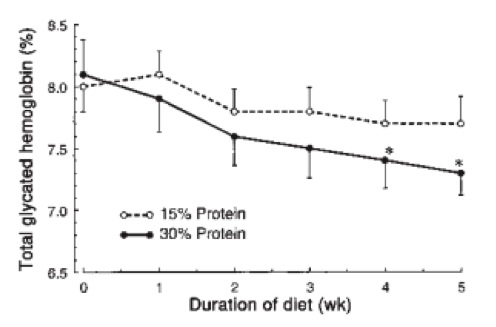

"Starchy foods, such as bread, pasta, rice and cereal, provide carbohydrate, the body's energy source. Fruit, milk, yogurt and desserts contain carbohydrate as well. Everyone needs some carbohydrate in their diet, even people with diabetes....The biggest difference between the USDA's guidelines and Joslin's is the recommendation of fewer carbohydrates and more protein in the diet, as recent studies have shown that this helps people eat less and lose weight... [diabetics should consume] 40 percent [of calories] from carbohydrates."Diabetes is diagnosed by demonstrating a glucose intolerance and therefore, the first line of therapy should be a reduction in glucose. Why is this logic not the first, most obvious treatment? Of course if the patient refuses, or they reduce their carbohydrates and their blood glucose levels continue to remain elevated, then further therapy is in order.

I believe it is because food is not "a hammer" physicians are equipped with. Medical training in nutrition is essentially absent apart from outdated vitamin deficiencies, yet doctors are expected to know it, so they default to the USDA's MyPlate for advice and information. This is seen as a constant, unchangeable variable in treatment of any food related disease, regardless of the etiology, given the label of "diet" or "lifestyle." Just the fact that alpha-glucosidase inhibitors are used as a treatment before a low carbohydrate diet confirms this.

Furthermore, if the patient is given a low fat high carbohydrate diet (as is the standard of care today) to manage their high blood sugar and they do comply with it meticulously, they will very likely need the insulin, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, and/or metformin to control their daily dose of 180 grams of the very nutrient they cannot tolerate.

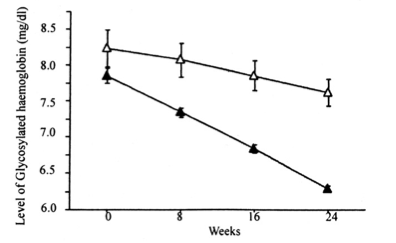

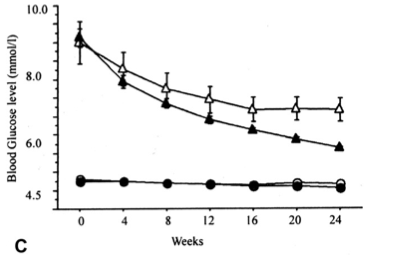

Clinical Trials

When you look for clinical trials testing this logic, you see things like this:

Treating Type 2 diabetes with food

Once you have a basic understanding of how the three major macronutrients alter your blood glucose and insulin levels, devising a plan to reduce blood sugar levels becomes simple.

- Carbohydrates of all kinds raise blood glucose AND insulin

- Protein spikes insulin AND DOES NOT seem to spike blood glucose, despite the theoretical ability of the amino acids to be converted into glucose via gluconeogenesis

- Dietary fat does not raise blood glucose OR insulin

- A decrease in carbohydrates, which spike blood glucose

- An increase in protein which acts to secrete insulin and thus reduce blood glucose (essentially

- acting as giving a patient insulin or sulfonylureas)

- An increase in dietary fat, which is insulin and blood glucose neutral.

Just make sure the fat is not trans fat as these cause diabetes 2 and therefore make it worse.

Note also that the poisoning of the modified electron transport chain (mETC) reaction in pancreatic beta cells by trans fatty acids affects also the production of the "glucagon inhibitor" which is secreted to turn off glucagon production in the alpha cells. A reduction in the inhibitor results in more glucagon and thus more glucose. In effect the high blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetes are a result of the individual producing his own glucose. Even fasting for a week will have no effect on extremely high blood sugar levels in advanced cases.

Diabetes results from a raised set point in the blood glucose control mechanism. In the advanced state the delta functions describing the set points for both halves of the heterodyne mechanisms are broadened due to the stochastic nature of the trans-fatty acid poisoning of the mETC substrate. In effect we have Gaussian line broadening of the set point distribution function for both insulin and glucagon production. As the lines broaden insulin and glucagon production go into contention leading to the apparent contradiction that in type two diabetes insulin levels get progressively higher as the poisoning advances and at the same time blood glucose levels become increasingly raised. This effect known as "Insulin Resistance" might better be described by the expression: "Glucagon Admittance" by analogy with electrical circuit theory.

The term "Insulin Resistance" might also be applied to the reduced uptake by body cells of glucose under the influence of insulin. This effect, also caused by trans fatty acid poisoning, is a part of the "metabolic syndrome" (a symptom descriptor) which causes almost all modern obesity. It is easy to cure.

The curability of diabetes (and indeed to some extent whether you are given diabetes in the first place) depends upon which one of four genetic subtypes you are. Curable types 'C' and 'D' are relatively rare in diagnosed cases.