OF THE

TIMES

"We have about 50% of the world's wealth but only 6.3% of its population. This disparity is particularly great as between ourselves and the peoples of Asia. In this situation, we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment. Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity without positive detriment to our national security. To do so, we will have to dispense with all sentimentality and day-dreaming; and our attention will have to be concentrated everywhere on our immediate national objectives. We need not deceive ourselves that we can afford today the luxury of altruism and world-benefaction."

~ US State Department, 1948

They claim 12 in the photo however I see only 10, if 12 than 60% means they supposedly have a total of 20.

The NWO are desperate to keep a lid on the 'covid' injuries and deaths until they can organise a world war. Lots of EU members had signed...

These old women won't be around to see the error of their ways or the fruits of their work. Their children and their grandchildren will. Grandma's...

Where did this person think she was? She should have had more respect for the locals she was walking amongst. The Indian people don't take too...

If the UN wants to be truly democratic, there should be no vetoes, simple as. The present UN system is by design. Its failures to prevent war are...

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

Look how distant stars are superimposed on the comet like closer stellar object.

[Link]

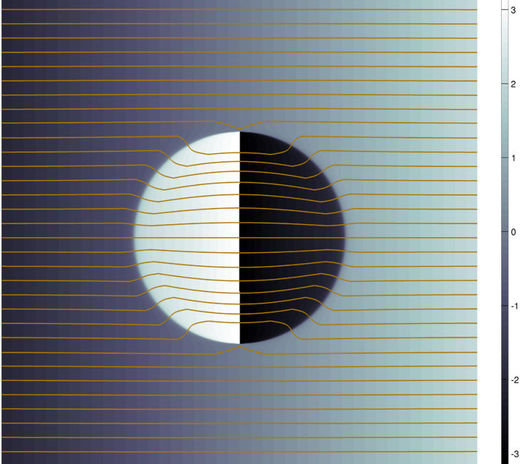

The light is bending around the super dense body and resuming its original path on the other side.

It is not completely invisibility though.

An infrared telescope working beyond 1000nm will clearly capture the thermal footprint of the star.