The brain naturally produces opioids, or chemicals with similarities to the drug. One of these, enkephalin, induced hungry rats to pounce on chocolate treats faster the more of the chemical they produced, researchers report online today (Sept. 20) in the journal Current Biology.

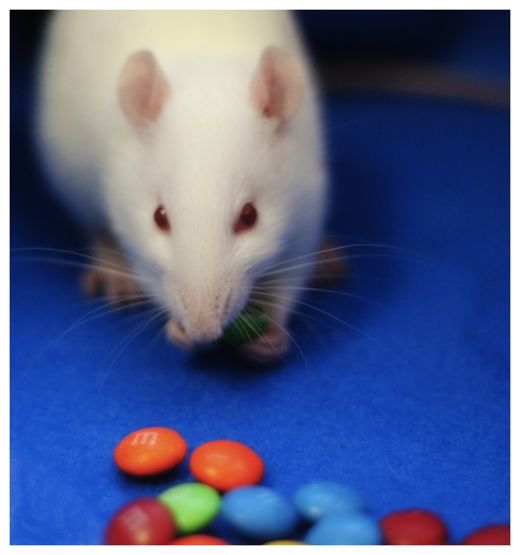

When scientists dosed the rats with a big jolt of enkephalin in a brain region called the neostriatum, the rats became eating machines, downing the equivalent of a 150-pound (68 kilogram) person eating 7 to 8 pounds (3.1 to 3.5 kg) of M&Ms in an hour, said study researcher Alexandra DiFeliceantonio.

"This drug injection causes them to eat just obscene amounts of food," DiFeliceantonio, a graduate student in biopsychology at the University of Michigan, told LiveScience.

Triggering gluttony

The surprise of the study, DiFeliceantonio said, was the brain region where the opium-like chemical acts. The neostriatum sits deep in the forebrain and is responsible for motor movements and habit formation. In movement disorders such as Huntington's or Parkinson's, this is the brain region that gets damaged.

But the new study suggests that the neostriatum plays a role in the reward systems of the brain, too, DiFeliceantonio said. She and her colleagues first measured enkephalin in this region of the brain in rats going about their daily business: playing, running around and gnawing on non-food toys. Next, the researchers gave hungry rats M&Ms. They found that enkephalin increases during these chocolate-y meals. And the more a rat's enkephalin went up, the faster they were to dig in to that first M&M.

The rats with naturally higher enkephalin didn't eat any more chocolate than their lower-enkephalin comrades, but the speed at which they started eating suggested there might be some sort of motivational effect at play. So, DiFeliceantonio and her colleagues injected enkephalin directly into the rats' neostriatum. They found the chemical doubled the amount of chocolate a rat would eat. A 10-ounce (300 gram) rat would eat a half-ounce (17 g) of M&Ms in an hour, DiFeliceantonio said, the equivalent of the aforementioned 8 pounds (3.5 kg) for a typical human.

"They don't really stop eating until you take the food away from them," DiFeliceantonio said.

The roots of motivation

The gluttonous rats raised the question of whether the animals liked the taste of the chocolate more when they were flooded with enkephalin, or whether they were simply more motivated to eat and eat and eat.

Fortunately, mammals - whether rats or human - tend to make the same faces when they find something delicious: In short, they lick their lips. By feeding chocolate to drugged and not-drugged rats and watching their reactions, the researchers concluded that the rats found the treats equally palatable, no matter their enkephalin levels. In other words, the change in eating behavior is caused by an increase in motivation to eat.

"I think what we've done with the drug injection is to artificially dial up this motivation system as far as it will go," DiFeliceantonio said.

The same brain region activates in humans when shown rewarding food, she said, suggesting that the brain's motivation circuits are scattered throughout the brain.

"You're basically built to eat a lot," DiFeliceantonio said. "It just makes these ideas about pharmacological treatments for things like obesity more difficult. You need to know the whole story before you can start on them."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter