© Unknown

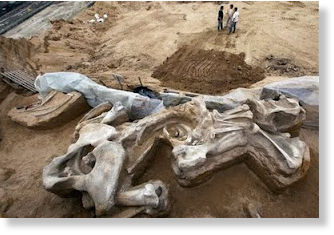

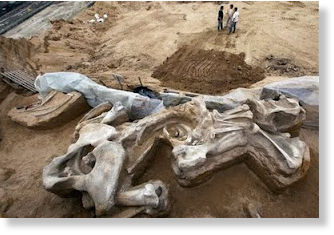

The world's first collective graveyard of a herd of mammoths has been discovered at the excavation site for coal in Serbia.

Heavy torrential rain earlier this week exposed the remains of what could be up to six mammoths, at an open pit mine in Kostolac, east of Belgrade not far from a site where two other mammoth remains had been uncovered in recent years.

Miomir Korac, director of the Archeological Project Viminacium, which is named after the Roman provincial capital along the Danube River, said that the discovery came as a complete surprise.

The archeologists were first alerted to one set of giant remains of a mammoth that was damaged by the mining machinery. But then the heavy downpour rinsed away the yellow sand.

Korac's team will now use infrared screening to get a better idea of what lies below the surface and check if there are additional mammoth bones.

"We will use all tools possible including tooth picks to scrape sand from the teeth, which could answer the epoch of the mammoths," ABC News quoted Nemanja Mrdjic, an archeologist of the team digging at the site, as saying.

Korac elucidated that the location covers an area of some 20.000 square meters on what could have been an island in the Pannonian Sea, which today is the most fertile land of Hungary, northern Serbia and Croatia.

The first prehistoric skeleton was discovered at this site in 2009. The bones belonged to a female mammoth that was named Vika.

Another mammoth skeleton, from a much later period, was discovered at a factory in Serbia in 1996 and was called Kika.

These particular creatures lived from 100,000 years ago to as long as one million years ago, Serbian and international scientist estimated after their excavation.

"This is a rare global treat because no such place exists elsewhere in the world," Korac said.

He added that international paleozoologists, paleontologists and archaeologists are likely to participate in the work to learn about life on earth millions of years ago.

"It's the luck of science," Mrdjic said.

"The location of the fossil, mostly held in loose sand, that is not very cemented is also a stroke of luck," Mrdjic added.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter