Chicago - B iomedical researchers talk about the day not too far off when DNA sequencing will be so cheap that everyone will have their genome sequenced and carry the results around on a flash drive. People will learn about their personal disease risks, helping their doctors and them prevent or treat these illnesses. But a new study throws cold water on the notion that whole-genome sequencing will be very useful for the average person.

Hopes for genomic medicine have grown in the past few years as researchers raced to track down DNA behind common diseases. These so-called genome-wide association studies have turned up hundreds of genetic markers linked to diseases such as cancer and diabetes. But the risks associated with such markers are usually quite low - often just a fraction higher than for people without the marker. Still, many scientists have hoped that once they found all the genetic markers for a disease, including rare ones that confer higher risk, the total risk carried by some individuals would be high enough - say, two times the normal risk - to merit taking preventive measures.

But the new study suggests that even if all the disease risk markers can be found, the genetic risk for most people will still be relatively low. This conclusion emerges from a study by cancer geneticists Victor Velcelescu, Bert Vogelstein, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University. They began by gathering existing data sets on diseases in thousands of twins, mostly in Europe. They assumed that identical twins have the same genetic risk of developing a specific disease. After examining 24 actual diseases in the twins, the researchers constructed a model that assumes each individual carries a certain "genometype," or total genetic risk, for each disease. Then they looked at how these risks would vary across the population.

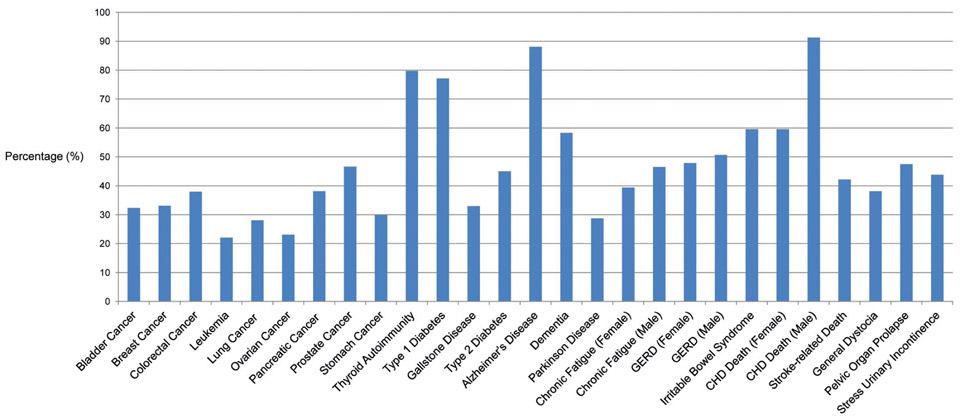

This analysis showed that in a best-case scenario, most people will have a genometype giving them a significantly elevated risk of developing one disease. But they will test negative for the other 23 diseases, even though they will later develop some of them. So a negative test should not lull people into a false sense of security, Vogelstein says. (There are a few exceptions: 75% of those who eventually develop thyroid autoimmune disease, type 1 diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, and (in men) coronary heart disease would have a positive genetic test.)

"We're not saying there's no point" to whole-genome sequencing, says Vogelstein, who presented the findings here today at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. (The results also appear today in Science Translational Medicine.) But "it's not going to reliably predict what disease people will get or die from." The results of the modeling may help health care organizations "get the most bang for the buck," he says. "They may want to pay for a membership to the gym," which would help ward off many diseases, instead of sequencing a patient's genome, at least for people with no strong family history of a disease, he says.

Harvard University genetic epidemiologist Peter Kraft says the study adds to others in the last 3 years that have dampened hopes that if researchers could find the "missing heritability," or all the genes that raise the risk of a particular disease, then genetic tests could help predict which patients will get sick. "There does seem to be an upper bound of what we can learn about common diseases with multiple causes," says Kraft, who thinks the paper illustrates why "we're not going to have a huge impact" on the average person with genome sequencing.

But geneticist Peter Visccher of the University of Queensland in Australia thinks genome sequencing will still become routine in the clinic because it is so valuable for identifying people at risk for less common diseases with a large genetic component, such as inflammatory bowel disease. "Genomic medicine is unstoppable because of the relentless drive of the technology that facilitates it," he says.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter