Scientists have long wondered whether propeller and engine noises from big ships stress whales out. Now, thanks to a poop-sniffing dog and an accidental experiment born of a national tragedy, they may finally have their answer.

Baleen whales use low-frequency sounds to communicate in the ocean. "They're in an environment where there's not a lot of light; they're underwater. They can't rely on eyesight like we do," says veterinarian Roz Rolland of the New England Aquarium in Boston. Some studies have found that whales alter their behavior and vocalizations when noise increases, and it stands to reason, she says, that noise pollution would hinder their ability to communicate and cause them stress. But because scientists can't control the amount of noise in the sea, that's been very hard to prove.

Researchers couldn't stop traffic, but the September 2001 terrorist attacks did. At the time, Rolland was collecting feces of right whales in the Bay of Fundy in Canada so she could try to develop pregnancy tests and other ways to study the animals' reproduction. Animals break up their hormones and get rid of the leftovers in their poop, so feces can show whether an animal is pregnant and reveal its levels of stress. Blood samples would do the same, but feces are much easier to collect.

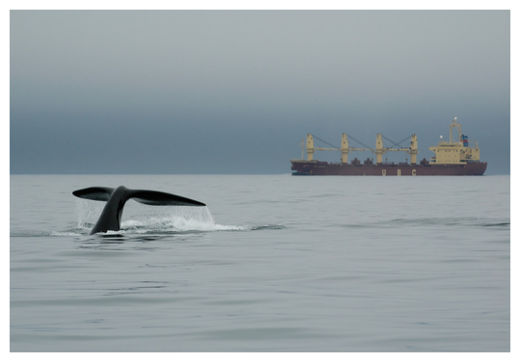

In the first few days after the terrorist attacks, ship traffic in the region decreased dramatically. "There was nobody else there. It was like being on the primal ocean," Rolland says. The whales seem to have noticed the difference, too. The levels of stress hormones in their feces went down, suggesting that ship noise places whales chronically under strain.

Rolland and colleagues made the finding with the help of an extremely sophisticated poop detector: a dog's nose. The dog - most often a Rottweiler named Fargo - stood at the prow of a research vessel, sniffing as the boat moved across the water. "You use the dog's nose as a compass because the dog will always put his nose into the strongest scent," Rolland says. As the driver turns the boat, "it's like the hot and cold game. The closer you get, the stronger the scent; and the more excited the dog gets, the more the tail wags. Then when you're there, the dog sits down and looks up at you, like, 'Where's my tennis ball?' " When that happened, a member of Rolland's team scooped the floating poop out of the water with a net, and the dog got his toy.

While Rolland's team was collecting feces, other scientists, including biologist Susan Parks of Syracuse University in New York, were recording sounds in the Bay of Fundy to understand right whale behavior. But it was only in 2009, when Rolland was preparing for a workshop on noise and cetaceans convened by the U.S. Office of Naval Research that she realized she could combine the two data sets. She and her colleagues compared poop and noise measurements collected between 2001 and 2005.

The only year when whales' stress hormones decreased was 2001, when noise and ship traffic also decreased. Overall noise decreased by 6 decibels, with a particular reduction in low-frequency noise, the sounds that right whales are thought to care about the most. Only three large ships passed by the right whales on 12 and 13 September 2001, compared with nine on 25 and 29 August (2 days when recordings were made).

Stress can interfere with the immune system and with reproduction. There are only 475 right whales in the western North Atlantic Ocean, and they have much lower reproduction rates than right whales that summer near Antarctica. Stress caused by noise could be part of the reason, the team reports online today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"I'm quite surprised that they saw such a large difference," says Michael Romero, an endocrinologist at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts, who studies stress in birds, Galápagos marine iguanas, and other animals. Some of his research has suggested that animals get used to disturbances over time and have lower stress hormone levels. "It's a terrific paper. They were able to do something that really it's difficult to imagine repeating, which is keeping boats silent for a fairly reasonable period of time," he says.

Since the experiment was unintentional, the scientists couldn't control it as well as they might have liked. They didn't have sound levels from before 2001, for example. Still, Rolland says the findings are cause for worry. "The big message is that there's enough noise in the oceans that we should be concerned," Rolland says. There may be ways to build quieter ships, but oil and gas exploration, wind farms, and sonar also emit the low-frequency sounds that seem to particularly bother whales. "It's sort of like dumping all of our solid waste and sewage into the ocean," she says. "There's a certain point at which people realize the oceans aren't limitless and they can't absorb all this we're dumping into them, and I think we're reaching that realization with noise."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter