It divides people. Some see it as a noble, disinterested use of Western power. Others see it as a smokescreen for a latter-day liberal imperialism.

I want to tell the story of how this idea originated and how it has grown up to possess the minds of a generation of liberal men and women in Europe and America.

It is the story of a generation who became disenchanted with traditional power politics. They thought they could leap over the old corrupt structures of power and connect directly with the innocent victims of war around the world.

It was a grand utopian project that began in the mid-60s in Africa and flourished and spread across the world. But in the 1990s it became corrupted by the very thing it was supposed to have transcended - western power politics.

And the idea seemed to have died in horror in a bombing of a hotel in Baghdad in 2003.

What we now see is the return of that dream in a ghostly, half-hearted form - where the confidence and hopes have been replaced by a nervous anxiety.

This modern phase of humanitarian intervention begins in 1968 with the Biafran war. It is a fascinating moment because it is where the framework - the contemporary filter through which we now perceive all humanitarian tragedies - was first constructed.

The Eastern part of Nigeria had declared independence and called their new state Biafra. In response the Nigerian army attacked the rebel government. Things went very badly for the Biafrans, but no-one in the West cared. While the British government happily sold lots of arms to the Nigerians.

But then the Biafran government found a very odd Public Relations firm in Geneva, called MarkPress who set out to change the way people in Europe saw the war.

I have discovered a great documentary in the BBC archive which tells what then happened. It is shot inside the PR company's offices and interviews the men running the campaign.

It shows how they turned a war that people saw simply as a political conflict in a faraway land into something heart-wrenching and dramatic.

It became a moral battle between evil politicians in Nigeria - aided by cynical and corrupt politicians in London who were selling the arms - and the innocent victims of the starvation caused by the war.

Here is an extract:

The British newspapers went for it in a big way. And a new movement grew up. It was driven by moral outrage, fuelled by a disgust with the old British political class who were prolonging the suffering through arms sales.

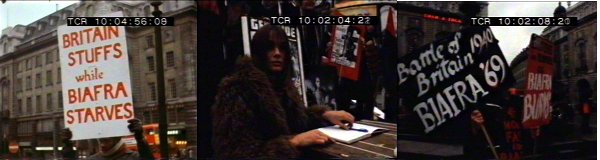

Celebrities joined in. They held a 48 hour fast in Piccadilly Circus over Christmas. Here are some frame grabs from the news report. The one that shows what was really happening is the placard that says "BATTLE OF BRITAIN 1940 - BIAFRA '69".

The conflict was being fitted to the template that was going to define the whole movement. It was the Good War. A justified resistance against evil to protect the innocent wherever they were being threatened in the world.

Just like the struggle against fascism in the Second World War.

But Biafra also revealed the terrible dangers of this simplified view of wars - dangers that would always haunt the humanitarian movement.

Here is an extract from a very good Timewatch programme about Biafra made in the early 90s. It has journalists telling how they took what Biafra's PR agency had started - and went much further. They created the new image that was going to define the future coverage of all these humanitarian crises - the starving child.

But the programme also makes a strong case that the aid that resulted from the wave of sympathy that these images created had a terrible unforeseen consequence. It prolonged a futile war for a further 18 months - and thus contributed to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Many in the aid agencies have denied this. But the programme includes the rebel Biafran leader, Colonel Ojukwu, saying clearly that he used the hard currency he got from the agencies to buy the weapons he needed to continue fighting.

Out of Biafra was going to come a new idea of how to save the world. And the man who would create it was a young French doctor called Bernard Kouchner.

Kouchner had worked for the Red Cross in Biafra, but he had become disgusted by the Red Cross' refusal to publicise the genocide created by the Nigerian government.

Just as the Red Cross hadn't revealed the horrors they saw in World War Two in the Nazi concentration camps because they insisted on being "neutral"

Kouchner resigned and went back to Paris where he founded a new humanitarian organisation called Medecins Sans Frontieres. Being neutral, Kouchner said, really meant being complicit in the horror. And MSF would never be complicit. It was on the side of the innocent victims.

Here is Kouchner explaining what he did:

Kouchner - and many of the others who founded MSF - had been Marxist or Maoist revolutionaries, but they had become disenchanted with those utopian visions. And what they were doing was reworking the politics of third world liberation into a new form.

It was a type of liberation that they believed went beyond the politics of left and right and instead was about saving individuals from the horrors of totalitarianism whether that came from the right or the left.

They weren't going to be neutral. They were going to take sides. But it was the side of the victims - because they were neutral.

Their first slogan was "There are no good and bad victims".

And in 1979 Kouchner dramatically demonstrated this belief. He hired a ship to go and rescue the Vietnamese boat people who were fleeing the communist regime who now ruled Vietnam.

The left - and many liberals - were shocked. Because these were "bad victims". Victims of the noble anti-imperialists who had defeated America.

But Joan Baez supported him.

Here is part of a film made in the early 1980 that tells the story of his rescue of the boat people. It was filmed on the ship Kouchner hired. You also get a very good sense of Kouchner's drive and his beliefs.

There is a great scene as the MSF ship arrives on a tiny Island. The Europeans stride weeping onto the jetty as they are applauded as heroes by the thousands of boat people stranded on the island.

At the same time as the humanitarian movement was rising up, so too were the new despots that were going to become some of the main targets for this new idealism.

Many of them - like Pol Pot, Saddam Hussein, and Muammar Gadaffi - were also, in a strange way, products of the failure of the Communist dream. Like Kouchner they too were trying to rework revolutionary theory - but in their case with horrific results.

I have found a sort of fly-on-the-wall documentary made in 1976 which follows Muammar Gadaffi around as he goes about ruling Libya.

One highlight is a section with his mother and father who still live in a tent out in the desert. Mrs Gadaffi explains how her son has insisted that they must remain living in their old tent until every other Libyan is properly housed in a modern apartment.

I wonder if they ever got out.

The documentary makes it clear how repressive and brutal Gadaffi's regime is. How he has locked up and tortured thousands of his opponents.

Comment: It does? Watch it for yourself and see how "reliable sources say" that Gaddafi's "regime" did such things.

But then it takes a fascinating turn. The interviewer asks Gadaffi to explain why he has sent Libyan troops to fight with the Palestinians against Israel, and why he has sent in Libyan agents to try and overthrow President Sadat of Egypt.

In response Gadaffi launches into an explanation that countries like Libya have a duty to intervene in other nations where the ordinary people are being oppressed by autocrats or oppressive governments - and help free them. That includes helping to liberate Egypt and Tunisia.

But it also means, he says, that politicians like him are justified in intervening in Northern Ireland to help the Provisional IRA. Because they are oppressed by the British government.

They too are victims.

What Gadaffi was arguing was a strange mirror image of the theory that Kouchner and the other ex-leftists in Europe were developing.

For they too were heading towards the idea of "armed intervention".

In the 1980s the humanitarian movement was flourishing - above all in Afghanistan. But in Afghanistan the movement also came up against a big political problem.

Men and women from what was now called "the doctors' movement" went in over the mountains to help the victims of the Soviet attacks. They were brave and daring and they saved the lives of many Afghan civilians.

But they also helped the Mujaheddin. Under the theory of the humanitarian movement this was fine. The Mujaheddin were resisting the Soviet totalitarianism. They were victims fighting back so it was morally right to help them.

But others didn't see it that way.

Here is video of the trial in Kabul in 1983 of a French doctor who had been captured by the Afghan army.

He is called Philippe Augoyard. He worked for Aide Medicale Internationale - which was another version of MSF. The trial is absurd - and in the tradition of all communist show trials the doctor reads out a "confession" and admits to "working with the counter-revolutionary bandits".

But there is also another part of his confession that was both true and embarrassing for all the ex-Marxists and Maoists in the humanitarian movement. The mujaheddin they were helping were backed, funded and armed by the Americans.

Which meant they were helping American global imperialism.

Incidentally, the video is shot by my hero. He is a cameraman called Erik Durschmied. He is the best cameraman who has ever worked for the BBC - and I am constantly using his stuff in my films.

But then a group of French philosophers came to the rescue. They came up with a theory that said it wasn't bad to work with American military power. In fact, if the humanitarians could harness America's armed might, they could use it to change the world in a revolutionary way.

The philosophers were led by another ex-Maoist called Andre Glucksmann. He had turned against the left and had developed his own theory which he called "anti-totalitariansm". Here is a picture of Glucksmann relaxing in 1978.

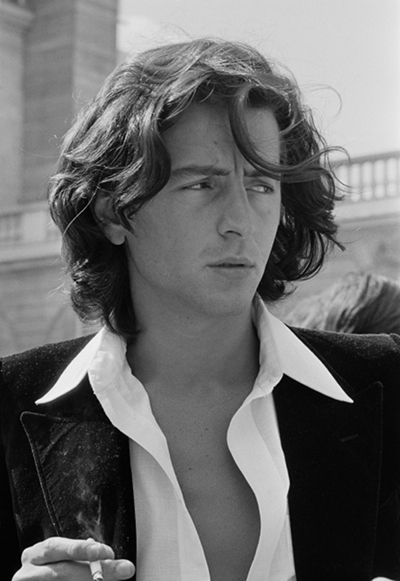

But he wasn't alone. Glucksmann was part of a group of intellectuals that rose up in France in the late 1970s called the New Philosophers. They saw Bernard Kouchner as an action hero putting their ideas into practice. Another prominent one was the glamorous Bernard-Henri Levy. Here he is with an interesting haircut.

Glucksmann put it in stark terms. Everything that oppressed people around the world he called "Auschwitz". Even famines were called "Auschwitz".

It was the ghost of the Second World War again.

Glucksmann then said that people with power had a right to intervene in other societies to prevent "Auschwitzes". And that included using American power.

Maybe, he said, power exercised by the strong was not always oppression. If it was used decently it could liberate the oppressed.

And - Glucksmann said - this didn't just mean medical help. It included "armed resistance".

And then came the massacre at Srebrenica in July 1995 - which seemed to prove Glucksmann's theory in a dramatic way.

When the Bosnian crisis began in 1992 humanitarian groups and the UN came in to try and help the victims of Serb aggression.

But they quickly began to realise they were being used by western governments as a way of containing a crisis that the politicians did not want to get involved with.

The journalist David Rieff wrote:

"The idea was simple, coarse and brutal. Instead of political action backed by the credible threat of military force, the Western powers would substitute a massive humanitarian effort to alleviate the worst consequences of a conflict they wanted to contain.And then at Srebrenica thousands of civilians gathered together in the enclave - believing they were under international protection. But when the Serbian troops led by General Mladic marched in, the UN troops did nothing. The promise of protection had simply made it easier for the Serbs to kill over 8,000 people.

'Containment through charity' was the way one UN official put it."

Here is an extract from a brilliant Panorama programme about the massacre. It includes notorious footage shot by a Serb cameraman on the day of the massacre. It is notorious because he allegedly edited out shots that show evidence of the killings.

But you get a sense from the footage of the impotence of the UN Dutch soldiers. It is the record of a terrible moment of moral failure.

It begins with thousands of Bosnians fleeing Srebrenica for what they think is the safety of the UN camp outside town.

One of the UN's special envoys in Bosnia, Jose Maria Mendiluce realised that Glucksmann was right:

"You don't reply to fascism with relief supplies. Only if we stop being neutral between murderers and victims, if we decide to back Bosnia's fight for life against the fascist horror of ethnic cleansing, shall we be able to contribute to the survival of the remnants of that country and of our own dignity."And then a few months later American air power - under the command of NATO - was used to force the Serbs to negotiate a peace. Almost no-one disagreed. It was a Good War in which the left-wing humanitarians were now allied with their old imperialist enemy - America.

Comment: Of course, there was nothing 'left-wing' about those 'humanitarians' - they were psychopaths wearing masks of sanity.

Out of Srebrenica came a strange new hybrid - a humanitarian militarism. And in the 1990s it rose up to capture the imagination of a generation on the left in Europe.

Ever since the collapse of the left in the early 1980s they had been searching for a new vision of how to change the world for the better. Now they found it - a humanitarianism that had the power to right wrongs around the world rather than just alleviate them.

It even had French philosophers behind it.

And one of that generation who was most entranced was Tony Blair, and in 1999 he took this humanitarianism to its moment of greatest triumph.

Here are the rushes of Tony Blair arriving to a hero's welcome in Kosovo in May 1999. Blair had persuaded a reluctant President Clinton to join in a NATO bombing campaign to stop Serbian atrocities in Kosovo and had stuck with it even when it seemed to be failing.

Blair's arrival and his speech at a Kosovan refugee camp on the Macedonian border is an extraordinary scene. It is also a very important moment in recent history. Watch Blair's face closely as he walks through the adoring crowd chanting "Tony, Tony, Tony" and you understand some of why he would take Britain to war in Iraq four years later.

It is also eerily reminiscent of Kouchner and the other doctors arriving on the South Sea Island to rescue the Vietnamese Boat people exactly twenty years before.

It was also a moment of triumph for Bernard Kouchner. He became the head of the interim administration in Kosovo - and he set out to create a new democracy.

Many of his staff were leftist revolutionaries from 1968. Even one of the NATO commanders had fought on the streets of Paris.

But Kouchner quickly discovered that victims could be very bad. There was an extraordinary range of ethnic groups in Kosovo.

There were:

Muslim Albanians

Orthodox Serbs

Roman Catholic Serbs

Serbian-speaking Muslim Egyptians

Albanian-speaking Muslim Gypsies - Ashkalis

Albanian-speaking Christian Gypsies - Goranis

And even - Pro-Serbian Turkish-speaking Turks

They all had vendettas with each other - which meant that they were both victims and horrible victimizers at the same time.

It began to be obvious that getting rid of evil didn't always lead to the simple triumph of goodness.

Which became horribly clear in Iraq in 2003.

Kouchner and many of the other humanitarian interventionists were wary of backing the invasion. They distrusted the Bush administration and suspected they and their ideas were being used as cover. But they also believed in removing Saddam Hussein because it was a chance to liberate millions of people from the oppression of a "fascist" tyrant.

Following the invasion many of those who had worked under Kouchner in Kosovo went to Baghdad to set up the United Nations presence there. They were led by another humanitarian, a Brazilian ex-leftist from the 1960s, Sergio Viero de Mello.

They set up their operations in the Canal Street Hotel in Baghdad. But then on August 19th - in the middle of a press conference - this happened.

A vast truck bomb had been driven right under the window of Sergio de Mello's office. He and 21 others were killed.

No one knows for sure who was behind the bombing but it was clear that de Mello and the humanitarians had been deliberately targeted.

Many in the humanitarian-intervention movement saw the Canal Hotel bombing as the beginning of the end of their dream. Because it dramatically illustrated how naive they had been.

The movement had begun back in Biafra because a group of young idealists wanted to escape from the old corrupt power politics. To do this they had simplified the world into a moral struggle between good and evil.

They believed that if they could destroy the evil - by liberating victims from oppression by despots - then what would result would be, automatically, good.

But the problem with this simple view was that it meant they had no critical framework by which to judge the "victims" they were helping. And the Baghdad bombing made it clear that some of the victims were very bad indeed - and that the humanitarians' actions might actually have helped unleash another kind of evil.

The same truth has become obvious in Kosovo too.

Last year a Swiss prosecutor produced a report for the Council of Europe which alleged that the Prime Minister of Kosovo, Hashim Thaci was not only a mafia boss, a murderer and a drug dealer, and alleged that he was also involved with a group that killed Serbian prisoners and then sold their organs for illegal transplants.

Hashim Thaci denies all the allegations

And it has also been alleged that Mr Thaci rigged the recent elections "on an industrial scale".

But quite a few people still believe in the dream.

Samantha Power was a journalist in Bosnia and a close friend of Sergio Viera de Mello. She is now a Special Assistant to President Obama. Power is a passionate advocate of humanitarian intervention - and by all accounts she is the person who most persuaded a reluctant President Obama to intervene in Libya.

And Bernard Kouchner also supports the Libyan intervention.

But there is a general wariness and nervousness about the return of the old dream of armed intervention. Above all because we realise that humanitarian interventionism offers us no political way to judge who it is we are helping in Libya - and thus what the real consequences of our actions might be.

Even if one's instincts are to help those fighting Gadaffi, it is no longer enough just to see it as a struggle of goodies against baddies. For it is precisely that simplification that has led to unreal fantasies about who we are fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Fantasies that persist today, and which our leaders still cling to - because they give the illusion that we are in control.

But the French philosophers are still very vocal. Here is Bernard-Henri Levy on Newsnight claiming he helped persuade President Sarkozy to intervene in Libya.

As you watch him - you get a sense that you are looking at something rather odd, a simplification of the world that was very much a product of a strange moment in history.

Rather like Mr Levy's hair-style.

Comment: It's a simplification of the world that is the product of a psychopathic mindset. Psychopaths always rise to the top, no matter their background as doctors, leftists, humanitarians...