One of the most persistent wartime images has selfless French men and women in berets and leather jackets blowing up bridges and ambushing columns of German soldiers on lonely country roads.

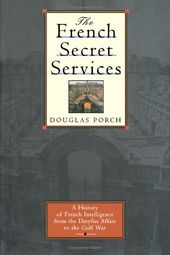

But a new book by historian Douglas Porch, The French Secret Services, contends almost nothing of the sort actually happened. His account has set the French seething - all the more so since many of them are aware that what he says is absolutely true.

According to the book, even those few French who helped downed airmen often did so for the money. The standard reward for getting an escapee into Spain was about $50,000 in today's money.

Porch notes that, contrary to the myth, the French Resistance didn't rise up after D-Day, June 6, 1944, to attack Germans behind the front lines. Sabotage of the Nazi war machine was minimal.

Only about 5 percent of the French were even nominally members of the underground. Of these, scarcely any ever fired a shot in anger, dynamited a train or sent a clandestine radio message.

Albert Speer, who headed German war production, was asked after the war about the effect of the French Resistance. He replied, "What French Resistance?"

Porch's work is significant because the yawning gap between wartime reality and myth is at the center of the self-doubt that has nagged the French psyche for the last 50 years. To reassure themselves about their national merit, the French have deliberately become extremely tough customers - especially when dealing with Americans.

As was remarked by Charles Bohlen, onetime U.S. ambassador to France: "The French have never forgiven us for liberating them."

The Resistance legend was almost entirely the work of Charles de Gaulle, wartime leader of the Free French government in London, and of the French Communists. He needed to build up his otherwise weak position in the eyes of the allies.

Porch says de Gaulle persuaded Dwight Eisenhower, the Allied supreme commander, to praise the Resistance as worth an "extra six divisions."

Both men knew the claim was false, the historian contends. Eisenhower wanted to please de Gaulle and felt the French leader had been treated roughly by Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman.

French Communists coined a slogan - "the party of the 70,000 martyrs" - the number they claimed to have been executed by the Germans. The true figure, according to Porch, was fewer than 350.

advertisement: French military rifle- never fired, dropped once due to hastened retreat