© unknown

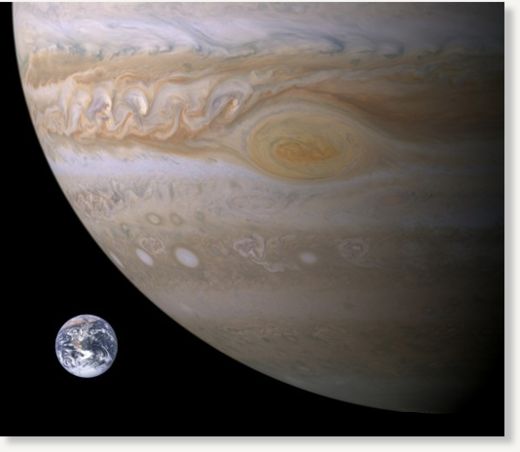

Bright Jupiter has dominated the evening sky for months. Jupiter is an impressive planet - it's 11 times wider than Earth - and its influence reaches farther than you might guess.

Now that winter is nearing its end, Jupiter has descended far down the western sky. Look for it low in the west about an hour after sunset as twilight fades. Tomorrow the thin crescent moon will shine to its right, as shown here. In the following days the thickening crescent moon will climb higher above it in the twilight.

Jupiter has more mass than all the other planets, asteroids, comets, and everything else in the solar system combined. So it throws a lot of weight around. Its moving gravitational field sometimes tugs asteroids out of their accustomed paths or sends wayward comets into Earth-approaching loops. When the sun and planets were new and still jockeying for position 4.6 billion years ago, Jupiter undoubtedly helped to arrange the whole solar system.

And to a small extent, it is still doing so.

As Jupiter sinks low in the west these evenings, its influence is holding together a swarm of asteroids located far away from it, very high in the southwestern part of the sky. Jupiter also shapes a second, similar asteroid swarm on its opposite side, very far below the horizon toward the northwest.

These asteroids are locked in a special relationship with the planet due to an odd combination of its gravity and the sun's. The swarms share Jupiter's orbit but precede it and follow it by about a sixth of a circle. Each swarm, Jupiter, and the sun form an equilateral triangle.

This is no surprise. As long ago as the 1770s, the mathematician Joseph Louis Lagrange figured out that a moving planet ought to create gravitational "low spots'' 60 degrees ahead of it and behind it in its orbit, where loose objects might collect.

Not until 1906 was he proven right, with the discovery of the first asteroid stuck in this spot with respect to Jupiter. As of now, astronomers have since found 4,892 of them. They are called Trojans, after the naming of the first one for a hero of the Trojan War.

Similarly, there are four known Mars Trojans sharing the orbit of the red planet, and seven known Trojans of Neptune.

And last month, astronomers working with NASA's Kepler space telescope reported an extraordinary find: twin

planets around another star that seem to share the same orbit in a Trojan relationship with each other.

Twin super-EarthsKepler has discovered some 1,200 likely exoplanets so far by the slight, periodic dimmings they cause if, by luck, they happen to pass across their star's face as seen from our direction. A faint, far, sun-like star known as KOI (Kepler Object of Interest) 730 is being crossed by no less than four planets in small, fast orbits with periods that are tightly locked to one another. All four are "super-Earths.'' Their silhouettes have 3.1, 2.3, 2.4, and 1.8 times Earth's diameter.

The middle two are the ones that share the same orbit, occupying each other's Trojan zones.

This discovery may be very relevant to the history of Earth. For at least a decade it has been increasingly clear that when Earth and the rest of the solar system were less than 1 percent of their present age, a Mars-size body hit the young Earth, splashed off a large part of its mass, and some of the debris collected to become the moon. The impacter has even been given a name: Theia.

But simulations show that the impact must have happened at relatively low speed to produce the moon correctly. In other words, Theia and Earth must have shared pretty much the same orbit beforehand. Now we see a planetary system where just a situation exists.

A large passing body in the chaotic young solar system would have been enough to break up the Earth-Theia pairing and make a crash inevitable.

So the surprises keep on coming. Sara Seager, a leading super-Earth specialist at Masschusetts Institute of Technology, has a prediction: "When it comes to exoplanets, the best is yet to come - and that statement will remain true forever.''

"For at least a decade it has been increasingly clear..."

Or do you just mean more ..."scientists"... are swallowing the notion?

"relatively low speed". That's a vague one. Relative to C or to walking pace? Lets anyone off having to evaluate whether combined gravitational pull would allow a "relatively low speed", doesn't it?