To put it in non-scientific terms, lead scientist Robin Bell told msnbc.com, the study redefines "how squishy" the base of ice sheets can be. "This matters to how fast ice will flow and how fast ice sheets will change."

"It also means that ice sheet models are not correct," she said, comparing it to "trying to figure out how a car will drive but forgetting to add the tires. The performance will be very different if you are driving on the rims."

Reporting in this week's issue of the peer-reviewed journal Science, Bell and his team described how ice-penetrating radar peeled back two miles of ice a million years old in the center of Antarctica.

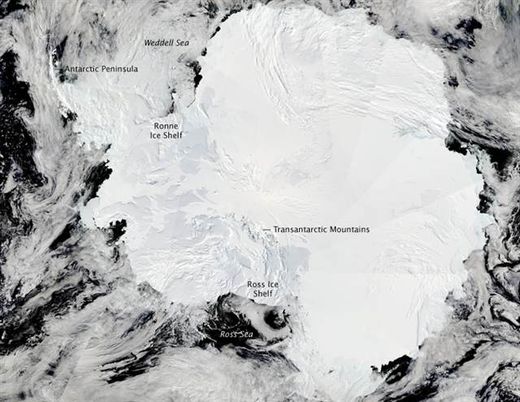

The images show that refrozen ice makes up 24 percent of an area known as Dome A, a 13,800-foot-high plateau roughly the size of California. Much of the sheet and refrozen ice lies atop an underground mountain range.

Ice from that area "drains into all the major ice shelves of Antarctica," the researchers wrote in their study. "Processes occurring in the Dome A region have the potential to affect the majority of East Antarctica."

While the field work was far inland, Bell believes the same will hold true along the edges of the icy continent. "We believe there is this ice rimming the ice sheets at the edge so this will impact how they will change," said Bell, a geophysicist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

The Antarctic ice sheets, some of it more than two miles thick, holds enough fresh water to raise ocean levels 200 feet if it all melted. That's not expected but even if a small part did melt it could threaten millions of coastal dwellers worldwide.

Given already known melt in Greenland and parts of Antarctica, the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change earlier estimated sea levels will rise between seven inches and two feet this century.

Bell said the study did not look at what kind of impact the refreezing would have. "We are not sure if it will make them go faster or slower," he said of ice sheets flowing into the ocean and thus raising sea levels.

How can water be sandwiched between the ice sheet and the continent?

"Deeply buried ice may melt because overlying layers insulate the base, hemming in heat created there by friction, or radiating naturally from underlying rock," Columbia University said in a statement along with the study. "When the ice melts, refreezing may take place in multiple ways ... If it collects along mountain ridges and heads of valleys, where the ice is thinner, low temperatures penetrating from the surface may refreeze it. In other cases, water gets squeezed up valley walls, and changes pressure rapidly.

"In the depths, water remains liquid even when it is below the normal freezing point, due to pressure exerted on it. But once moved up to an area of less pressure, such supercooled water can freeze almost instantly."

Ted Scambos, lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo., told msnbc.com that the finding was "unexpected in its scope" but he also felt it would be limited to the interior of East Antarctica, not the more vulnerable coastlines.

"I think it is an astounding discovery," added Scambos, who was not involved with the study. "Who knew that a buried mountain range would let you grow the ice sheet from underneath?"

Bell said that "the important message" is that while ice experts have long known of underground water systems "greasing the bottom of ice sheets," and thus potentially undermining them, "we never considered that they might be important for the actual structure of the ice sheet."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter