The benefits of calorie restriction are well documented in animals, but now the results have been replicated in a close relative of man over a lengthy period.

Over 20 years, monkeys whose diets were not restricted were nearly three times more likely to have died than those whose calories were counted.

Writing in Science, the US researchers hailed the "major effect" of the diet.

It involved reducing calorie intake by 30% while maintaining nutrition and appeared to impact upon many forms of age-related disease seen in monkeys, including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and brain atrophy.

Whether the same effects would be seen in humans is unclear, although anecdotal evidence so far suggests people on a long-term calorie-restricted diet have better cardiovascular health.

The precise mechanism is yet to be established: theories involve changes in the body's metabolism or a reduction in the production of "free radical" chemicals which can cause damage.

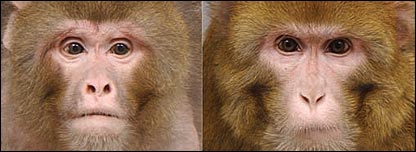

Seventy-six rhesus monkeys were involved in the trial, which began in 1989 and was expanded in 1994.

Half had their diets restricted, half were given free rein at feeding time.

The rate of cancers and cardiovascular disease in dieting animals was less than half of those permitted to eat freely.

While diabetes and problems with glucose regulation were common in monkeys who ate what they wanted, there were no cases in the calorie controlled group.

" People would have to weigh up whether they are prepared to compromise their enjoyment of food for the uncertain promise of a longer life "In addition, while most brains shrink with age, the restricted diet appeared to maintain the volume of the brain at least in some regions.

Catherine Collins BDA

In particular, the areas associated with movement and memory seemed to be better preserved.

"Both motor speed and mental speed slow down with ageing," said Sterling Johnson, a neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine.

"Those are the areas which we found to be better preserved. We can't yet make the claim that a difference in diet is associated with functional change because those studies are still ongoing.

"What we know so far is that there are regional differences in brain mass that appear to be related to diet."

Earlier this year, German researchers published findings from their study of elderly people which suggested that calorie reduction appeared to improve memory over a period of just three months.

Various studies on the positive effects of calorie restriction on the life spans of various organisms - from yeast to dogs - have been published over the last 70 years

But dieticians sounded a note of warning.

"Monkeys may be a close relation but there are significant differences which means not everything we see in them can be translated to humans," said Catherine Collins, spokeswoman for the British Dietetic Association.

"And there should be some serious reservations about cutting calories so dramatically, particularly for anyone under the age of 30. Any such diet would need to be very balanced to avoid malnutrition, and it would be a long-term commitment.

"People would have to weigh up whether they are prepared to compromise their enjoyment of food for the uncertain promise of a longer life, and a life which could be dogged by all sorts of problems - including osteoporosis."

There are numerous studies that show people who are a bit chubby live longer and are healthier. It's not how much you eat, it's WHAT you eat.