|

| ©SOTT |

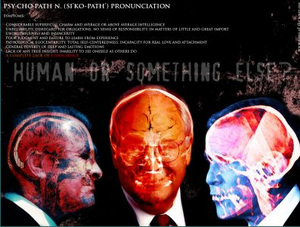

Some people just don't get it.

Ken Gude is a senior advisor to the Institute for Public Policy Research's Commission on National Security in the 21st Century. He wrote a piece called "Tortured Explanations" that ran this weekend in the Guardian. It is a review of a book by Philippe Sands on who drew up the current US torture policy.

Well, in the first paragraph we find this pearl:

Ever since the first horrific images from Abu Ghraib emerged almost exactly four years ago, I have repeatedly asked myself: how in the world could my country be responsible for such terrible things? I know a lot of people out there think that this is not an aberration and believe the worst about the United States, its motives and its actions. The Bush administration has certainly added a lot of fuel to that fire. But in this case, the "hate America" crowd are simply wrong: never before in the modern history of the United States has there been an officially sanctioned, government-wide system of inflicting torture and abuse on detainees. Until now.Oh, yeah. The "hate America crowd". That group of loony tunes who have this irrational hatred of the US for no reason at all.

Well, what planet is Mr Gude doing his research on? Has he never heard of the School of the Americas? Of the training of "interrogators" used throughout Latin America during the last fifty years who tortured anyone arrested or kidnapped for opposing the dictatorial regimes there? Are we quibbling here because torture in Latin America was officially denied while it was carried out? Doesn't that say more about the moral authority of the US people fifty years ago than anything else? Back then, the brainwashing and dumbing down weren't complete. The government could torture and train torturers, it just couldn't admit it was doing so.

Now, the climate has changed.

But the idea I want to address is presented in his next paragraph:

Figuring out how and why all of this transpired is vitally important to ensuring it never happens again. The excerpt from Philippe Sands' new book, Torture Team - carried here in the Guardian today - illuminates some of the critical decisions that got us into this mess. Looking back on these actions in hindsight, it is easy to see the errors of judgment. But it is important, however, to try and put yourself in these officials' shoes, feeling what must have been an awesome sense of personal failure at the loss of 3,000 lives on their watch and a deep sense of responsibility to prevent any future attacks. Initially, you must to have some sympathy for the incredible strain they would have been under. But as the catalogue of catastrophic decisions piled up, that feeling evaporates. We are left to conclude that these were the wrong people in the wrong jobs at the wrong time.Catch that? We have to put ourselves in their shoes. In other words, we need to feel some empathy for the criminals that did this, empathy for people who are incapable of feeling empathy themselves.

Of course, that is how the system works, that is how the deviants continue to fool us: they convince us to project our own humanity onto them. We have no idea that there could be individuals who look like us, who dress and talk like us, but who are incapable of feeling anything for another person. Therefore, we project our own internal states onto this humanoid thing in front of us and assume that they feel the same thing that we do.

Then they mirror the physical expression of our emotions back to us to convince us that they do indeed feel the way we do.

They don't.

They use our own empathy against us.

Until you understand this essential difference between us and them, you will continue to come up with apologies for psychopathy like the one delivered to us by Mr Gude.

Here is an excerpt from a remarkable novel, The Incredible Charlie Carewe, by Mary Astor, that gives a picture of the 'inner life' of a psychopath, the way they compute their responses in order to attain their aims.

Charlie Carewe is the son, 12 years old in this passage, of a wealthy family. He has just come close to killing the son of family friends by repeatedly banging the boy's head on a rock. His father is lecturing Charlie.

After you read this, you'll never see the psychopath in the same way:

The list of "thou shalt nots" in Charlie's mental card index was increasing. Whenever he wanted to, he could refer to them as something to be avoided because they interfered with the pleasures of living. Thus "Thou shalt not steal--money from the cash box in the kitchen because it will be missed more quickly than a dollar or two from Mum's handbag." And "Thou shalt not swim too soon after a meal--it will cause a bellyache" was catalogued ahead of "Thou shalt not remove a book from Dad's library--he raises an awful row."There it is. It is like the logic of a computer programme, a series of if/then statements designed to achieve a specific goal. Plug and play.

The latter was just too silly. He had been keeping a scrapbook of famous people with the name of "Charles" and in a volume of French history there was a painting of a certain Charles IV, which he fancied because he was called "Charles the Fair." He had thoughtfully used a razor blade to cut it neatly out of the book. Unfortunately the razor had cut through several pages which he had put into the wastebasket, and his care in returning the volume to its proper place on the shelf had gone unappreciated. In his father's mind this was inexplicably cross-filed with another, quite different and very funny episode. It amused Charlie to write his initials in the sand at one end of the beach when he was urinating, but it took much more skill and was infinitely more satisfactory to do the same thing neatly in the center of the white oval rug in front of Mum's dressing table. With his legal lingo, his father had lumped both things together as "Wanton defacement of personal property."

But there was a difference as anybody with any common sense could see, because the "defacement" of Mum's rug had precipitated one of the rare sound thrashings he was often threatened with but rarely dealt. The sound thrashing was not nearly as bad as it sounded, either. His father cuffed him around for a while, and then, because it tired him, Charlie supposed, he would go over and put his head in his hands on the desk and tell Charlie to "Go on now, and remember this as a lesson to you." It did make things sticky around the house for a while, so it was a good idea to avoid such consequences. And nothing cleared the air so quickly as those magic words "I'm sorry" and everybody positively beamed if one said, "How could I be so stupid?" or seemed to brush away a tear. Boy! What fools people were.

At that moment Charles was feeling brilliant. He was adding a valuable item to the index: "Thou shalt not lose thy temper." It was practically like a lecture with illustrated slides they had sometimes in school. The subject was "the danger of letting one's emotions run away with one" and Dad said, "you obviously lost your temper when you were wrestling with Roger, and as a result he was seriously hurt. [Charlie had smashed Roger's head repeatedly into a large rock on the beach.]" But the best part of it all was that as along as he remained quiet and attentive, Charlie could watch his father become what he was talking about. His face got redder and redder, he began to walk faster up and down the library, and once he pounded the desk with a crack that must have hurt his hand. It was very interesting.

[Charlie's father is trying to explain why nearly killing Roger was wrong.] "You're no different from other human beings, Charles. We all of us have to keep watch on our passions for our entire lives, otherwise they will control us instead of our controlling them." How to explain that they could be channeled, used as fuel for ambition, to overcome wrong? "Most of them are a kind of hangover from the Stone Age, I guess--when all we had was our fists to claim what belonged to us. But just take a look those fists of yours--they almost claimed a boy's life."

Charles caught the expression on this face and mirrored it. He heard the tone of his voice and became an echo. Looking at his hands, he said solemnly, "A boy's life," and his voice was an awed whisper.

His father rose and, putting an arm about the boy's shoulders, walked him to the door. "Don't dismiss it too soon, Charles--think it over--think it over." And Charles went out of the room shaking his head, still looking at his fists, a perfect picture of bewildered remorse.

Charlie was having a wonderful time. He had acquired a new toy that delighted him with its effectiveness. It contained innumerable ways of getting attention--of the pleasant kind. Heretofore there had been times when kids or grownups looked at him too suddenly, with widened eyes and open mouth, and it made him want to scratch himself or get out of the way. Now, as a result of a few words that his dad had said in the library, he had found a whole new world. To himself in the mirror above the washbasin in his bathroom he said, "Dad, I'm grateful to you." His voice slipped a little and he relaxed his throat and tried it a tone lower: "Dad--thank you." While he was about it he studied his face, staring hard, and by concentrating a little his eyes filled. "That's enough, that's enough," he whispered. More would look babyish.

[His mom calls, and he loudly blows his nose before greeting her.] "Why, Charles baby, have you been crying?" [...]The answer to this wasn't quite clear, so he played it safe, saying nothing, keeping his eyes down. [...] "But mother, what have I done?" He pulled away from her and buried his face in his hands, which gave him a chance to listen more closely for his next cue. [...]

"I'm just a leftover from the Stone Age," he said hollowly.

Beatrice bit her lip, to suppress a smile. "Well, cave man," she said, "you'll grow up to be a Carewe and a gentleman, don't you worry."

"Thank you, Mum dear. I love you very much."

They don't feel. They can't feel. All they can do is mimic.

But until we really understand that, we will fall, as has Mr Gude, for the ploy that we need to put ourselves in their shoes.

of these beings that walk on two legs is all around. In movies, songs, books, the psychopath is present as a living breathing creature. Unfortunately, most people do not think this is possible. They write it off as fiction or nightmares. They can't go past the comfortable thought, perpetrated by psychopaths, that we are all the same.