|

| ©BBC |

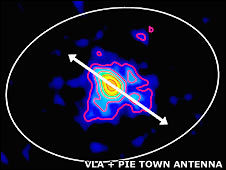

| Radio emissions from the HLTau system show the planet (top right) |

The ball of dust and gas, which is in the process of turning into a Jupiter-like giant, was detected around the star HL Tau, by a UK team.

Research leader Dr Jane Greaves said the planet's growth may have been kickstarted when another young star passed the system 1,600 years ago.

Details were presented at the UK National Astronomy Meeting in Belfast.

The scientists studied a disc of gas and rocky particles around HL Tau, which is 520 light-years away in the constellation of Taurus and thought to be less than 100,000 years old.

The disc is unusually massive and bright, making it an excellent place to search for signs of planets in the process of formation.

The researchers say their picture is one of a proto-planet still embedded in its birth material.

Dr Greaves, from the University of St Andrews, Scotland, said the discovery of a forming planet around such a young star was a major surprise.

"It wasn't really what we were looking for. And we were amazed when we found it," she told BBC News.

"The next youngest planet confirmed is 10 million years old."

If the proto-planet is assumed to be the same age as the star it orbits, this would be some one hundred times younger than the previous record holder.

'Record holder'

|

| ©BBC |

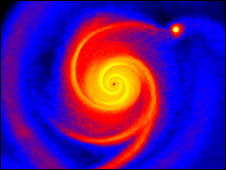

| Growth of planet |

Using the Very Large Array (VLA) of radio telescopes in the US, the researchers studied the system at emission wavelengths specifically chosen to search for rocky particles about the size of pebbles. The presence of these pebbles is a clue that rocky material is beginning to clump together to form planets.

In the UK, scientists used the Merlin radio telescopes based on Jodrell Bank in Cheshire to study the same system at longer wavelengths. This allowed them to confirm the emissions were from rocks and not from other sources such as hot gas.

In addition to detecting super-large dust in the disc around HL Tau, they also saw an extra bright "clump" of material.

This confirmed a so-called "nebulosity" seen a few years earlier at about the same position, by a team led by Dr Jack Welch of the Berkeley-Illinois-Maryland Array, US.

Formation theories

Dr Ken Rice, from the Institute of Astronomy in Edinburgh, said the discovery shed new light on theories of planet formation.

According to one model, planets form from the bottom up. Under this scenario, particles of rocky material collide and "stick" to one another, forming a bigger and bigger object.

But he thinks the proto-planet in HL Tau formed relatively quickly when a region of the disc collapsed to form a self-contained structure. This could occur because of gravitational instability in the disc itself.

Dr Rice said his computer simulations were such a good fit for the observations that it seemed the mechanism might really operate in nature.

Intriguingly, another young star in the same region called XZ Tau may have made a close pass of HL Tau about 1,600 years ago.

Although not required for planet formation, it is possible that this flyby perturbed the disc, making it unstable. This would be a very recent event in astronomical terms.

"It's possible it gave a 'yank' to one side of the disc around HL Tau, making it unstable, and that this was a 'trigger' for the planet to form," Dr Greaves explained.

"If the planet formed in the last 1,600 years, that would be incredibly recent."

The Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting 2008 continues until Friday at Queen's University Belfast.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter