|

| ©Unknown |

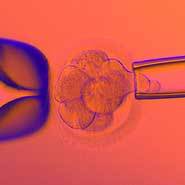

| The Newcastle cybrids lived for three days

and the largest grew to contain 32 cells |

Embryos containing both human and animal material have been created in Britain for the first time, a month before the House of Commons is to vote on new laws to regulate the controversial research.

A team at the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne announced tonight that it had successfully generated "admixed embryos" by adding human DNA to empty cow eggs, in the first experiment of its kind in the UK.

The achievement will heighten debate over the ethics of human-animal embryos, as the Commons prepares to debate the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill next month.

While Parliament has been promised a free vote on clauses in the legislation that would permit admixed embryos, their creation is already allowed under existing legislation, subject to licence from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA).

The Newcastle group, led by Lyle Armstrong, was awarded one of the first two such licences in January, together with another team at King's College, London, headed by Professor Stephen Minger.

The new Bill will formalise their legal status, should it be passed by Parliament.

Admixed embryos are widely supported by the scientific community and patient groups, as they provide an opportunity to produce powerful stem cell models for investigating diseases such as Parkinson's and diabetes, and for developing new drugs.

Their creation, however, has been vociferously opposed by religious groups, particularly the Roman Catholic church. Cardinal Keith O'Brien, the head of the Catholic church in Scotland, described the work last month as "experiments of Frankenstein proportion".

The admixed embryos created by the Newcastle group are of a kind known as cytoplasmic hybrids or "cybrids", which are made by placing the nucleus from a human cell into an animal egg that has had its nucleus removed. The genetic material in the resulting embryos is 99.9 per cent human.

The BBC reported that the Newcastle cybrids lived for three days and that the largest grew to contain 32 cells. The ultimate aim is to grow these for six days and then to extract embryonic stem cells for use in research.

Once the technique has been tested, scientists hope to create cybrids from the DNA of patients with genetic diseases. The resulting stem cells could then be used as models of those diseases to provide insights into their progress and to test new treatments.

It is already illegal to culture human-animal embryos for more than 14 days or to implant them in the womb of a woman or animal and these prohibitions will remain in the new legislation.

By using cow eggs in their experiments scientists can avoid using human eggs, which are in very short supply. There are also ethical difficulties involved in collecting human eggs for research, as the donation process carries a small risk to women.

Professor John Burn, a member of the Newcastle team, said: "This is licensed work which has been carefully evaluated. This is a process in a dish and we are dealing with a clump of cells which would never go on to develop. It's a laboratory process and these embryos would never be implanted into anyone.

"We now have preliminary data which looks promising but this is very much work in progress and the next step is to get the embryos to survive to around six days when we can hopefully derive stem cells from them."

Even though the experiments have already been approved by the HFEA they will deepen controversy over human-animal embryos because MPs have yet to have an opportunity to vote on the issue.

At present, the work is permitted under the watchdog's interpretation of the 1990 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, but this legislation does not specifically mention admixed embryos.

The Newcastle team's decision to announce their success on television, before their results have been published in a peer-reviewed journal, will also trigger criticism from scientists.

Medical researchers said last night that the experiments are important but that they wanted to see published details before passing judgement on their merits.

Martin Bobrow, Emeritus Professor of Medical Genetics at the University of Cambridge, said: "I have no idea whether this is true or not but Dr Armstrong has been working towards this for a long time and has recently been given a license to pursue this research. It is very unhelpful to speculate about how significant they are until we have more facts.

"If it turns out to be true that he has so rapidly been able to create an embryo that could produce a medically useful stem cell line, then that would be a very strong argument for pursuing that particular technique."

Peter Andrews, Professor of Biomedical Science, at the University of Sheffield, said: "The production of embryos by transferring the nucleus of an adult human cell to a human egg from which its own nucleus has already proved very difficult, let alone by combining a human nucleus with an animal egg. Apparently these researchers have achieved some success, but by using the nucleus from a very early embryonic cell, which might be easier to reprogram than an adult cell.

"However, at the moment it is impossible to assess the significance of this report until we know more details of what has been achieved, the results have been repeated and, importantly, they have been reviewed by independent researchers in the usual way."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter