|

| ©Reuters |

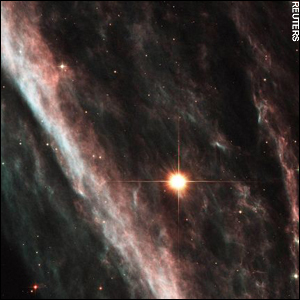

| Hubble telescope photo of a supernova. Scientists use these to study distant galaxies |

The idea that time itself could cease to be in billions of years - and everything will grind to a halt - has been set out by Professor José Senovilla, Marc Mars and Raül Vera of the University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, and Univerisity of Salamanca, Spain.

The motivation for this radical end to time itself is to provide an alternative explanation for "dark energy" - the mysterious antigravitational force that has been suggested to explain a cosmic phenomenon that has baffled scientists.

A decade ago, astronomers noticed that distant supernovae - exploding stars on the very fringes of the universe - seemed to be moving faster than those nearer to the centre, suggesting that they were accelerating as they shot through space.

Dark energy was suggested as a possible means of powering this acceleration of the expansion of the cosmos.

The problem is that no-one has any idea what dark energy is or where it comes from, and theoreticians around the world have been scrambling to find out what it is, or get rid of it.

The team's proposal, which will be published in the journal Physical Review D, does away altogether with dark energy. Instead, Prof Senovilla says, the appearance of acceleration is caused by time itself gradually slowing down, like a clock that needs winding.

"We do not say that the expansion of the universe itself is an illusion," he explains. " What we say it may be an illusion is the acceleration of this expansion - that is, the possibility that the expansion is, and has been, increasing its rate."

Instead, if time gradually slows "but we naively kept using our equations to derive the changes of the expansion with respect of "a standard flow of time", then the simple models that we have constructed in our paper show that an "effective accelerated rate of the expansion" takes place."

While the change would be infinitesimally slow from an ordinary human perspective, from the grand perspective of cosmology - in which scientists study ancient light from suns that shone billions of years ago - this temporal slowing could be easily measured.

Astronomers are able to discern the expansion speed of the universe using the so-called "red shift" technique.

The principle is the same as that of an ambulance siren which gets higher as it comes towards the listener but lower as it moves away. Similarly, a star moving away appears redder in colour than one moving towards us.

Scientists look for exploding stars - supernovae - of certain types that provide a benchmark to work against.

However, the accuracy of these measurements depend on time remaining invariable throughout the universe.

If time is indeed slowing down, so that according to this new suggestion our solitary time dimension is slowly turning into a new space dimension, then the far-distant, ancient stars seen by cosmologists would therefore, from our perspective, look as though they were accelerating.

"Our calculations show that we would think that the expansion of the universe is accelerating," says Prof Senovilla.

The group bases its idea on one particular variant of superstring theory, a so called theory of everything, in which our universe is confined to the surface of a membrane, or brane, floating in a higher-dimensional space, known as the "bulk".

In some number of billions of years, time would cease to be time altogether - and everything will stop.

"Then everything will be frozen, like a snapshot of one instant, forever," Prof Senovilla tells New Scientist magazine. "Our planet will be long gone by then."

However, he adds that the team is only assuming there is one dimension of time. Itzhak Bars of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles has put forward the bizarre suggestion that there are two dimensions of time, not the one that we are all familiar with.

Prof Senovilla says: "One thing that is definitely not included in our models is the possibility of having more than one time dimension."

While the theory is outlandish, it is not without support. Prof Gary Gibbons, a cosmologist at Cambridge University, believes the idea has merit. "We believe that time emerged during the Big Bang, and if time can emerge, it can also disappear - that's just the reverse effect," he says.

"The wonderful thing about these explanations is that, strange as they sound, the Large Hadron Collider could provide evidence for extra dimensions in the universe," comments Dr Brian Cox of Manchester University, referring to the atom smasher in Geneva that will start up next year.

"If that happens, then these kind of theories will move out of the realm of speculation and into the mainstream."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter